The NIEO Past

The NIEO’s roots reach back to the post- World War II settlement and developing countries’ frustrations at the Bretton Woods conference of 1944. Already then, there was widespread dissatisfaction from delegations like those of India, China, Egypt and Mexico about the Agreements’ lack of development content, assumption of a fixed international division of labor, imbalanced quotas, and enshrining of the US dollar as the global reserve currency.1 However, it was not until the 1960s that a major, pro-South program of reforms to the global economy emerged, primarily through the contributions of the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Under the leadership of Argentine economist Raúl Prebisch, UNCTAD functioned for the developing countries as a sort of alternative to the international financial institutions (IFIs), which had been designed largely by and for the developed countries.2 Acting as the “Group of 77” (G77) bloc established at UNCTAD I in 1964, the countries of the South could caucus and strategize to change the rules of trade and finance in their favor – or at least get a better seat at the bargaining table.

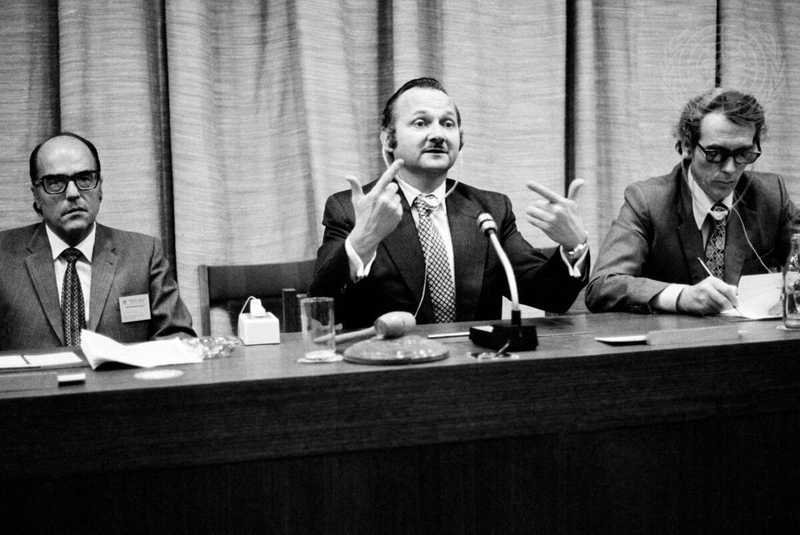

The seeds of the NIEO were planted at UNCTAD III, held in Santiago, Chile in 1972, where Mexican President Luis Echeverría put forth a Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States. But the event that pushed the NIEO from idea to practice was the 1973-74 oil crisis. We now know that the oil price increases initiated by Arab members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in October 1973 were part of a longer arc of Third World efforts toward ‘economic decolonization’ and development, culminating in the 1974 Declaration on the Establishment of a New International Economic Order (NIEO) at the United Nations.3 The goal was to fundamentally transform the crumbling postwar economic order in their favor through comprehensive economic negotiations; the weapon was the newly-proven economic might of cash-flush OPEC members. “What we aim,” explained Venezuela’s president and OPEC leader Carlos Andres Perez, “is to take advantage of this opportunity when raw materials, and energy materials primarily, are worth just as much as capital and technology, in order to reach agreements that will ensure fair and lasting balances.”4

The US government was united in its opposition to the NIEO but divided in its response. In the Ford administration, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger’s eagerness to quickly pacify the South through concessions on trade and aid was opposed by neoliberal economic advisors like Treasury Secretary William Simon and Alan Greenspan, who charged him with sabotaging their own deregulatory crusade at home. Kissinger was by no means sympathetic to the NIEO, but he did not see declarations as a true threat to the international order. Further, he believed that outright opposition to it would alienate anxious US allies in Western Europe, whose dependence on global South commodities (especially oil) was far more severe.

Elsewhere, the NIEO split American liberals into two camps. On the one side were a growing number of “neoconservative” Democrats. The NIEO conflict was not simply a battle between rich and poor nations, Irving Kristol insisted in his Wall Street Journal column, but “much more a question of one’s attitude towards liberal political and economic systems, and toward liberal civilization in general.”5 In Commentary magazine, neoconservatives drew direct connections between the domestic New Left’s attacks on postwar “vital center” liberalism on US college campuses and the Third World’s attacks on the post-World War II “liberal international order” at the UN. This camp’s first victory came with Ford’s appointment of self-described “Harry Truman Democrat” Daniel Patrick Moynihan as UN ambassador. Moynihan’s call for the United States to “go into opposition” against the postcolonial UN majority won him wide support at home but left the US isolated from North and South alike.6

On the other side were the “world order liberals” behind the Trilateral Commission and later the Carter Administration. On a self-described mission to “make the world safe for interdependence,” the Carter team promised to put North-South relations at the top of its agenda and proposed to turn its signature foreign policy initiative – human rights – into a global campaign to meet “basic human needs” in poor countries. But the G77 suspected (correctly) that Carter’s focus on attacking poverty within countries was intended to end the discussion of global structural reform, whatever Carter’s personal sincerity about the former goal. In fact, the “realist” Kissinger proved more willing to compromise on certain aspects of aid and trade than the earnest, proudly liberal Carter Administration. In the end, world-order liberals’ insistence on maintaining US primacy in international institutions outweighed their commitment to delivering more and more effective anti-poverty aid.7

By the end of the decade, a combination of Northern opposition (led by the US) and Southern division (OPEC vs. the “No-PECs”) had left the NIEO on the ropes. The knockout punch came in 1979, when the US Federal Reserve drastically raised interest rates (the Volcker shock) to stop inflation. It worked, but at the cost of a massive debt crisis beginning in Latin America and spreading into Africa and parts of Asia, resulting in a “lost decade of development” for many countries. The counter-NIEO movement had had its intended effect, as Ronald Reagan pursued a generally hostile attitude toward the UN, then shared by many Americans, including Democrats.8 At the same time, the Reagan administration restored US leadership in IFIs. At the IMF, neoliberalism’s policy trifecta – privatization, liberalization, and fiscal discipline – became dogma as the dreaded “Washington Consensus.”9 At the World Bank, president A. W. Clausen (a former Bank of America CEO) and Chief economist Anne Krueger placed the blame for Third World poverty on bad governance and pushed structural adjustment as a precondition for loans.10 Once development’s handmaiden, the state was now its obstacle, stifling the wishes of billions of entrepreneurs-in-waiting.11

In short, the American foreign policy establishment dropped its concern for global inequality as soon as the NIEO met its demise, while once-marginal neoconservative and neoliberal views became mainstream. The Reagan Administration immediately nixed economic and social rights from its agenda, but so did congressional Democrats. Instead, human rights in US foreign policy reemerged in the 1980s as powerful weapons against Cold War adversaries accused of political abuses – essentially where they sit today.12

The NIEO Present

Who benefited from the forty years of neoliberal globalization that came in the NIEO’s wake? Economist Branko Milanovic has crunched the numbers, and the results are simpler than one might expect: “The great winners have been the Asian poor and middle classes; the great losers, the lower middle classes of the rich world.”13

Market reforms and the removal of barriers to trade and capital in rich and poor countries alike encouraged the growth of a new global middle class, especially in large countries such as India and China. On the whole, this has resulted in a relative convergence of global incomes, from which one might conclude that neoliberal globalization achieved what the NIEO desired: the reduction of inequality, especially between the rich North and the poor South. Removing China or India from the equation, however, leaves a different impression. Without the gains from these two countries, global inequality in this period actually increased. Of course, neither China nor India bought the neoliberal model wholesale, and the state remains primus inter pares in the national economy: they are the exceptions proving the rule. And even with China and India, global inequality decreased most significantly after 2008, meaning that stagnation in the North following the Great Recession is also helping to close the gap.14 Indeed, the economic gains during neoliberal globalization’s high point were, for most Americans, meager. From 1993 to 2018, average real incomes per family in the United States grew by 30 percent – basically, just enough to keep up with consumer prices (which is no longer true given current inflation). However, if one removes the top 1 percent, growth in average real incomes for the other 99 percent drops by 11 points. Meanwhile, the top 1 percent saw their incomes grow by an astonishing 100.5 percent through the Clinton, Bush, and Obama years.15

Facing low wages, regressive taxes, unresponsive bureaucracies, expensive and employer- dependent health care, and endless war in the Middle East, it is no wonder so many Americans now see themselves – and, to an extent, their country – as victims of globalization rather than its beneficiary and steward. This is the irony of US foreign policy’s defeat of the NIEO. The North’s reconstitution of the world order along global and domestic free-market principles in the 1980s and beyond increased the costs of US primacy abroad while leaving an economy at home where the benefits are overwhelmingly redistributed upward. The result at home was an unsustainable bargain of cheap consumer goods and credit in lieu of wage increases, universal healthcare, and affordable housing and higher education – again, where the United States is largely stuck today.

The NIEO future

The NIEO may have perished with the 1980s debt crisis, but the G77 (and China) is stronger than ever in one forum that receives more attention than analysis: global climate change negotiations under the UN Framework Convention.

North-South relations have always been central to global environmental governance, from the 1972 Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment (establishing UNEP) to COP-1 in 1995, where parties agreed that climate negotiations could only proceed on the basis of Common But Differentiated Responsibility.16 At every stage, the South’s concerns have gone beyond notions of sustainable development to include structural reforms to the global economy. Here, too, the US has traditionally sought a leadership role, as the Nixon Administration did at Stockholm and as the Obama Administration did at Paris. But like in the NIEO negotiations, the US and its allies’ unwillingness to endow South-controlled global environmental institutions has been matched with a failure to deliver on more modest promises (including but not limited to development aid). I do not pretend to have anything like a blueprint for a “new NIEO” – and I think progressive internationalists should not discount the utility of regional economic cooperation, especially on climate adaptation – but it strikes me that this is where the action is, and it’s where we should be acting. So, I’ll conclude with three major problems in global climate negotiations, which I believe any neo-NIEO would have to address.

One, there is the problem of profit, in the sense that all the money is to be made in climate change mitigation in rich and (some) middle-income countries. Adaptation is generally not profitable, at least in the short-term, but it’s badly needed in all countries and particularly in poor ones. Many people on Wall Street truly believe that climate change is now solved because Tesla makes money and BlackRock backs GFANZ. But if governments and IFIs are already subsidizing their profits – and they are – then governments and IFIs, not BlackRock, should assert control and determine priorities. Every dollar that a government spends on keeping itself above water is a dollar taken from domestic spending on health, education, and general welfare. This should be a moral principle and an economic one.

Two, and related to one, are the risks inherent in the giant unregulated securities market for “green” and “blue” bonds. There are worse uses for global North institutional investors’ capital glut, and we have seen some successes recently with insurance programs tied to automatic stabilizers, like in Jamaica. However, there exists almost no legal framework for this booming market, and the philosophical framework – government and IFI guarantees to New York, London, and Paris banks – we have seen before.17 There need to be rules and coordination.

Three, there is a complete lack of donor accountability. At COP26, developed countries were rightly pilloried when it was revealed that they would not meet the annual $100 billion in climate finance they had promised back in 2009. It was also revealed that only about 10-12% of the $80 billion they were funding would come as grants. At COP26, the United States promised some $12 billion in climate finance; in March, Congress approved only $1 billion. So we talk about quantity and quality, but had rich countries met their promises over decades – official development assistance and otherwise – we would already be in a very different place.

Michael Franczak is a Research Fellow in the Division of Peace, Climate, and Sustainable Development at the International Peace Institute and Visiting Fellow in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author of Global Inequality and American Foreign Policy in the 1970s (Cornell University Press, 2022).