Introduction: Learning is the starting point of internationalism

Srećko Horvat

In 1959, eight months after the revolution in Cuba and the overthrow of the Batista dictatorship, the Cuban Goodwill Mission led by Ernesto "Che" Guevara embarked on a world tour that would bring the Cubans for the first time to socialist Yugoslavia. After visiting Egypt, India, Burma, Japan, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Pakistan, Yugoslavia would become the only country in Europe that they visited.

From 12 to 21 August, the delegation of Cuban revolutionaries travelled across Yugoslavia. First, they visited Belgrade, then Kragujevac, Sarajevo, Jablanica, Konjic, Rijeka, Opatija, Ljubljana, Postojna and Maribor. Although it was initially not clear — for reasons further explained later — whether Tito would be able to receive them, in the end they met the Yugoslav president and members of his cabinet at his summer residence on the Brijuni Islands on 18 August 1959.

Only after 50 years, two decades after socialist Yugoslavia collapsed with a brutal war, the transcript of this historic conversation was published, after being rediscovered at the Archive of the President of the Republic, Archive Yugoslavia.

It is significant for several reasons, not merely because of its clear historical value, but also because it envisioned a new Non-Aligned Movement. The conversation explored how cooperation between revolutionary movements and governments could power the emergence of a multipolar order. That, in turn, could confront the intertwined crises that have only accelerated since 1959: from the climate crisis and forever war — both rooted in the logic of capitalist accumulation — to the threat of nuclear annihilation.

But let us first tackle the question of why it took 50 years for the transcript to be published — and why this historic meeting between two revolutionaries and statesmen, Tito and Che, received so little attention at the time.

There are at least two possible explanations.

1. Explanation: "Since this conversation won't be published in the press…"

One explanation comes from the conversation between Tito and Che itself. In one part of the transcript, Che recounts the Cuban delegation’s Burma experience and says to Tito: "Since this conversation won't be published in the press…"

Perhaps the Cubans, embarking on their first diplomatic offensive, simply did not want to make their efforts public so as not to endanger the freshly-established diplomatic relations with friendly governments and possible allies. There is also the fact that, in August 1959, the Communist Party of Cuba was still not formed and it was unclear whether it would side with the Soviet Union.

On the other side, since the Tito-Stalin split in 1948, Yugoslavia had pursued an economic and foreign policy that did not align with the interests of the Soviet Union or its Eastern Bloc allies, while at the same time building relations with countries that were not part of the two existing Cold War blocs.

As we can see from the transcript, the conversation between Tito and Che in Brijuni was friendly and pragmatic, but perhaps it was too soon — the Non-Aligned Movement would be founded two years later in Belgrade — to announce the alignment between Cuba and Yugoslavia?

2. Explanation: How Selassie overshadowed Che

Tito and Selassie in Pula, Yugoslavia, 1959

Another convincing explanation, which sheds light on the internal situation in Yugoslavia at that time and its foreign policy, comes from the journalist Giacomi Scotti, who reported about Che's visit to Rijeka for La voce del popolo in 1959.

That day, according to Giacomo Scotti, “the sea and the sky were brilliant, the trains, buses and ships were full of tourists; Yugoslavia was the only socialist country in Europe that opened its borders to globetrotters from the West. Of the five members of the Cuban delegation, four were dressed in simple military uniforms; one had a thick black beard, and the remaining three, including Guevara, had sparse beards... Finally, they were young, the idea of a revolution at the beginning of a long journey."

Che Guevara in Rijeka, 1959 photo by Petar Grabovac (Novi List), on the far right is journalist Giacomo Scotti.

Scotti also describes vividly the enthusiasm with which the Cuban delegation was welcomed. When they visited the "3 maj" shipyard in Rijeka, they were greeted by more than 2,000 workers. (For context: the factory employed around 8,000 workers at its peak. Today, it employs under 1,000 — another emblematic case of the so-called "transition" period, which was characterized by privatizations and the destruction of the main pillars of Yugoslav industry.)

However, the visit of the Cuban Delegation of Goodwill — not only to Rijeka — was underreported in the press, earning only brief reports from press agencies. The covers of Yugoslav newspapers were dominated by Josip Broz Tito and the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie, who was visiting the Marshall's residence at Brijuni.

This seems like the most plausible explanation. While Yugoslavia was one of the first countries to recognize Cuba’s socialist government, it had a longer and more-established diplomatic relationship with Ethiopia. It established its first diplomatic relations in the postwar period in Africa in 1952 precisely with Ethiopia. Then, in July 1954, Haile Selassie visited Yugoslavia, and Tito visited Ethiopia in 1955 as part of Yugoslavia's "Third World" diplomacy initiative in the wake of the 1948 split with the USSR.

A glance into the pragmatism of two revolutionaries

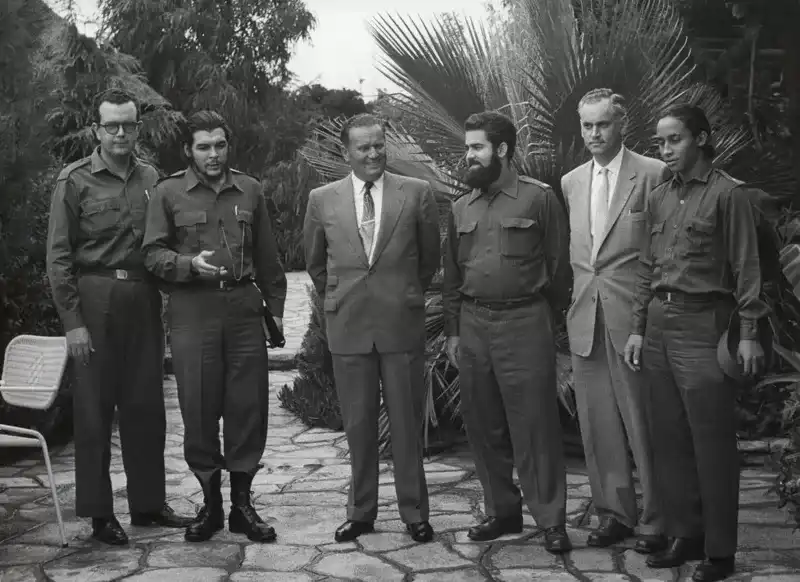

Che & Tito at Brijuni Islands, Yugoslavia, 1959

In the end, both explanations can be true at the same time — the Cubans did not want to reveal details that they were discussing with Tito publicly because their global diplomatic offensive was just beginning, while Yugoslavia was careful to maintain its newfound non-aligned status and attached more significance to its diplomatic relations with Ethiopia.

Whatever the reason, the transcript is a fascinating account of a meeting between two revolutionaries who now led socialist governments. It represents a unique glance into the pragmatic cooperation and strategies of non-aligned countries even before the Non-Aligned Movement was officially founded.

In fact, it would be founded just two years after the Tito-Che meeting — in 1961 in Belgrade. Although the cornerstones for NAM were already laid on Brijuni Islands in 1956 when Tito hosted Nehru and Naser, and of course, its origin has to be traced back also to the year 1955 and the Bandung Conference.

When Che and Tito met at Brijuni Islands, a luxurious kurort of the Austro-Hungarian Empire since the mid-19th century now turned into Marshall's summer residence, it was a meeting of two revolutionaries: one who just came to power after the successful Cuban Revolution on a diplomatic tour, and the other who was a guerrilla leader during WWII and would remain in power long after Che's death.

When they met, Che was 31 years old. Tito was 67. A few years later, Che would leave Cuba, travelling across the world and supporting or leading revolutionary struggles. He would meet his end at the hands of US military-backed Bolivian soldiers on 9 October 1967, at the age of 39. Tito would die, aged 87, in 1980. His last foreign visit, in tense and almost hostile conditions, was in 1979 when he met Fidel Castro in Havana.

In a way, the Brijuni conversation between Tito and Che represents the very beginning of the long journey of both Cuba and Yugoslavia — and the Non-Aligned Movement. For that reason, it should be of interest to internationalists across the planet.

The diplomacy of Non-Alignement before NAM

The conversation between Tito and Che sheds light on the very beginning of the relationship between Cuba and Yugoslavia. Over time, that relationship would be strained as Yugoslavia and Cuba began to pursue conflicting paths. This divergence culminated with the NAM meeting in Havana in 1979 when Castro called for the transformation of NAM into a "strategic reserve" for the Soviet bloc. Tito was opposed to the idea and the Yugoslav stance prevailed at NAM, although Cuba was the host country and Castro organized everything in order to win. In short, Castro didn't like Tito, because he was too close to the West, and Tito didn't like Castro, because he was too close to the Soviets.

Later that year, in December, the situation became more complicated for NAM. The Soviet Union intervened in non-aligned Afghanistan to support its communist government against the US-backed Mujahideen insurgency. The next month — in January 1980 — Tito died. Both events changed the future of the Non-Aligned Movement forever. Ten years later, socialist Yugoslavia collapsed. The Cold War, it seemed, was over.

Now, we were told that we live in the happy 1990s, at the "end of history". Concretely, in the case of ex-Yugoslavia, that meant massive privatizations and a period of structural adjustment, casting the population into debt and poverty. Built over decades, Yugoslav diplomacy collapsed overnight — with rare exceptions, like Budimir Lončar — and NAM lost one of its leading and founding members.

What makes the Tito-Che conversation interesting today is not only that it unveils a missing link in the chapter of our common revolutionary history and the history of the Non-Aligned Movement.

It is not simply a meeting between two revolutionaries who are coming together to join arms in the struggle against imperialism, colonialism, hegemony and oppression. What we see here is a glance into successful diplomacy and the politics of non-alignment before the Non-Aligned Movement emerged.

Not only did Tito promise to support Cuba at the United Nations, one of the concrete outcomes of their meeting was the opening of embassies both in Belgrade and in Havana already in the same year.

Agrarian reform, weapons, and the economy

Agrarian reform was one of the central themes of the conversation. No wonder, because only three months before Che and the Cuban delegation met Tito, Cuban’s revolutionary government had already eliminated latifundios — large-scale private-owned farms — and nationalized corporations that owned arable land.

So after the introductory exchange, Tito and Che — who was at that moment Minister of Industry and governor of the Cuban National Bank — swiftly turned to practical matters.

In the transcript, Che asks Tito what a reasonable limit on the size of property might be in the process of implementing agrarian reform. Yugoslavia had already walked that path in 1945 when its agrarian reform abolished bigger properties, and expropriated properties from banks, companies, church, and major landlords.

After exchanging practical advice, they dive into the theoretical possibilities of an invasion into Cuba and the role of the United States. Tito warns Che that "Cuba is becoming an example, and the Americans are therefore afraid that there will be a disturbance in their neighborhood."

Then they talk about weapons. Cuba was, Che said, quite isolated, while Yugoslavia had already supported anti-colonial struggles not only through diplomacy, but also by supplying weapons to resistance movements across the so-called "Third World" (which includes Tito smuggling a load of arms and ammunition for the Algerian Liberation Front on his iconic ship Galeb).

Besides the question of agrarian reform and weapons, both sides were interested in economic cooperation. The Cubans needed agricultural machinery, generators and household appliances, which Yugoslavia was interested in exporting. At that stage of Cuba’s historical trajectory, just after the revolution, Yugoslavia was important not just for its role in the Non-Aligned Movement. It also served as an example of the how the economy could be democratized, giving workers management rights in companies and industries, while distributing surplus value to the working class and society.

"We came to Yugoslavia to learn"

At one point of the conversation Che Guevara says to Tito, "We came to Yugoslavia to see your experience and to learn from it in the best possible way." The Battle of Neretva — which Che learned about on his visit to the town of Vogošća — obviously left a big impression on the young revolutionary, who raises the issue with Tito in their conversation.

The Battle of Neretva, named after the Neretva river in Bosnia and Herzegovina, was the final stage of the Fourth Enemy Offensive when the combined Axis powers launched an offensive against the Yugoslav Partisans throughout occupied Yugoslavia in 1943. The Yugoslav side faced heavy losses — the Germans claimed to have killed about 11,915 Partisans, executed 616, and captured 2,506 during the offensive. But the Partisans succeeded in regrouping and continued the guerrilla war. They would emerge victorious, liberating Yugoslavia and establishing a socialist self-management system. "We consider your victory in the war to be truly epic", Che says to Tito.

Che's conversation with Tito speaks to the critical importance of education — and of learning about our common history — in the process of revolutionary construction. Che indicates that Cuba would be interested in sending a number of people to study in Yugoslavia, but fears that language may be a problem, as "our peasants barely know how to read and write".

The Yugoslav side responds that language learning has never been an obstacle for students from Asia and Africa, and Tito says: "in our school Sudanese, Indonesians and many others got an education."

In fact, thousands of African and Asian students studied in Yugoslavia during the years of actually-existing socialism and the most propulsive period of the Non-Aligned Movement. And, vice versa, as the Croatian historian Tvrtko Jakovina shows, Yugoslav experts were asked to establish universities in Angola and Madagascar: "Yugoslav experts also taught in Addis Ababa, while thousands of foreign students came to Yugoslavia to study. In the late 1970s, three Ethiopian ministers were Yugoslav students. Yasser Arafat, leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization, who was supported by the SFRY in various ways, expressed his gratitude to Tito for 'training Palestine pilots' in Yugoslavia."

The transcript of the Brijuni conversations ends with Che sharing a story with the Yugoslavs: "In India, I talked with Krishna Manon about establishing bilateral relations, and he told me to send a professor or a doctor to India as our representative. I laughed and answered — what professor, we do not have any."

As Tanja Petrović points out in her magnificent essay on the Tito-Che conversation, in the years to come after the Cuban mission, Cuba managed to educate professors, doctors, engineers, artists. Both Cuba and Yugoslavia raised literacy dramatically. According to UNESCO, Cuba's literacy rate among people older than 15 years is 99%. While in pre-WW2 Yugoslavia (in 1921) 50% of population older than 10 years was illiterate, in 1948, due to mass literacy campaign during the war and after it, the percentage dropped to 25%. In 1961, 21% of population was illiterate, and in 1981, illiteracy was reduced to 9.5%.

Reducing illiteracy; providing free education, universal healthcare, public housing, self-management; and building the Non-Aligned Movement — these were all fundamental contributions provided by actually-existing socialism not only to 20th century history but to humanity itself. Today, both reality and memory are dominated by actually-existing capitalism. It is our task not only to recover memory, but to save the dead from an enemy who never ceases to be victorious, as Walter Benjamin puts in his sixth thesis.

What the Tito-Che conversation shows is that the struggle against imperialism and colonialism, "peaceful co-existence" and "the right to self-determination", non-interference in the affairs of other states and complete disarmament — to name just some of the fundamental principles of non-alignment — cannot be achieved without learning, without the recovery of memory and without saving the dead from the enemy.

Learning is the starting point of internationalism.

Discussion

Che Guevara (ECG): We came to Yugoslavia to learn from your experience.

Josip Broz Tito (JBT): [W]e are very interested in your struggle and experience, especially your current experience.

ECG: We thought that with our revolution we had rediscovered America. However, if we had met a country like Yugoslavia earlier, we might have started our revolution even sooner. If we had the opportunity to study other people's experiences, many things would be easier for us, the solutions of which we had to find ourselves. Yugoslavia, of course, is not the only country we visited. We also visited other countries, for example, Indonesia, where we found palm trees and similarly colored army uniforms.

Comrade Gošnjak: At the reception in Belgrade, [the Cuba mission] especially complained about the leaders of Burma, who did not want to receive them at all.

ECG: Since this conversation will not be published in the press, I can tell you what happened to us in Burma, where we stayed for only two days. We informed the Burmese of our arrival by telegram from Cairo. When we arrived in Rangoon, we were received by the Minister of Foreign Affairs, who told us that the Prime Minister was busy. We also visited the Minister of Trade and Agriculture to discuss trade and agrarian reform. In the capital of Burma, we had a discussion with the American attaché about our situation. I told him that we will go further in implementing the agrarian reform and our other plans, even though interference from the outside is very disturbing. It was a very nice conversation, even diplomatic, if you will. However, after that, all lunches and visits that were scheduled in this country were cancelled. In connection with the supply of rice for sugar, we were received only by some second-rate persons, and Burma did not accept this arrangement.

We were very well received in Egypt and Indonesia. In India, we were also well received, although a little quietly. We were well received in Pakistan as well. In Japan, you could say we were not welcomed at all. Due to the attitude of the Japanese, an agreement on trade could not be reached. The chamber of commerce told us that Japan would very much like to trade with Cuba but that it is not in their power because there are also higher powers. We couldn't even get a visa for Iraq. After Yugoslavia, we will visit Sudan, Ghana and Morocco.

JBT: It is the fate of all revolutions in small countries to have difficulties. Many are wary of them, some are against them, and very few support them. You will still have a lot of trouble in your fight. But when you have already thrown off the old regime, difficulties need not discourage you. It is more difficult to maintain power, but you will succeed if you are persistent. Of course, it is important not to make a big mistake now and to proceed gradually, step by step, taking into account the international situation, internal possibilities and the balance of forces. Some things you will have to keep for better times. You need to stabilize now. In my opinion, it would be dangerous to rush fully into agrarian reform. It would be better to do it gradually. The armed part of the revolution has been carried out in your country, the people expect something, and you must carry out a part of the agrarian reform. But you must also try not to allow yourself to be isolated abroad.

ECG: What, in your opinion, would be a reasonable limit on the size of the property?

JBT: In implementing agrarian reform, even we proceeded gradually, although the situation was different here. I don't know; maybe it is the same with you. We first confiscated the land of traitors and war criminals, and then we moved gradually. I think the situation is similar in your country as well. I am unfamiliar with the latifundios in Cuba, and it would be difficult to say how much they should be limited. It is certain that there are large, medium and small ones. Since there are mostly medium and small landowners, I would spare them now and start with the largest ones.

ECG: In Cuba, the agrarian reform is very mild because ownership of 1,300 hectares of arable land is allowed. Nevertheless, the agrarian reform affects 99% of latifundistas — mainly five American companies — which have over half a million hectares of arable land.

Leo Mates: Then it is no longer just an internal state problem but also a problem of relations with the USA.

JBT: That is another matter. The government should issue a declaration stating that these companies will not be deprived of their land without compensation. By doing so, you would gain a lot in the world in moral terms.

ECG: Actually, it is not a matter of confiscation but expropriation, for which compensation will be determined according to the amount of the tax return.

JBT: As Nasser did.

ECG: The companies requested that the compensation for this land be paid immediately, and we proposed that it be done in 20 years, with 4.5% interest. We said that we can pay them immediately if the war criminals from Cuba who are now in America are expropriated.

Grgur Cviličević: According to the constitution, it seems that the Cubans are obliged to pay immediately.

ECG: The government has powers both under the constitution and from congress. We have changed the constitution. Based on this change, we can pay the compensation within 20 years. The Americans refer to the old constitution. We asked them what they see as the difference between Cuba and Japan, where, during the implementation of the agrarian reform, it was agreed that compensation would be paid within 20 years at 2-3% interest.

JBT: The situation is different, after all. Cuba is close to America, and what happens there can affect other surrounding countries. In that part of the world, Cuba is becoming an example, and the Americans are therefore afraid there will be a disturbance in their neighborhood.

ECG: Officially, we cannot state that difference.

Comrade Popović: This is not about a statement but about material interests.

ECG: We are well aware. The difference is that the Americans did not have land in Japan, but [in Cuba] they do. Regarding agrarian reform, there were differences of opinion between the communists in South America. We were only going to limit the latifundistas and not implement a wider agrarian reform. However, we were forced to accommodate the [demands] of the peasants and implement this kind of agrarian reform. We moved ahead, although the communists and others from our movement thought we should be careful.

JBT: Yes, that is a problem.

Grgur Cviličević: The Cubans are quite isolated in Latin America. There is no government, except in Venezuela, that helps them in a sense. The president himself in Venezuela, in their opinion, is an enemy of the revolution in Cuba. But the Venezuelan people are broadly anti-American and prevent the president from taking a worse stance toward them.

ECG: We are, indeed, quite isolated. During the revolution in Guatemala, the major countries of Latin America — Argentina, Mexico and Brazil — were on the side of the progressive movement in Guatemala. Now, these countries are not helping the revolution in Cuba because they themselves have a difficult situation. We are not isolated from Venezuela, Ecuador and maybe Chile. However, these countries are not as important in South America as the larger states.

JBT: All the more, one should be more careful.

ECG: It could be said that the situation is such that we have some work ahead of us. The Americans have elections coming up, and at this moment, they cannot do anything bigger against Cuba. Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic, through which the Americans can carry out aggression, are themselves in a very difficult situation because of the revolutionary movements there. Those revolutionary groups are still quite small, but judging by our experience, we know what possibilities exist when the guerrillas start. Perhaps Khrushchev's trip to the USA is the reason why the Americans were a little more lenient towards Cuba at the Pan-American Conference in Santiago.

JBT: The USA is not the only state that is lenient towards Cuba, but following the conference, the whole situation is like that.

Comrade Popović: How do you view the United Nations?

JBT: It would be good to hear [the Cubans’] opinion on what could be done for them in the United Nations, to probe the terrain in case stronger pressure is needed. How do they view it?

ECG: We certainly plan to secure a better situation for ourselves with the help of the United Nations. The first step will be to expose the Organization of American States, which is an instrument of the USA. If we don't succeed, we think we should ask for help from the United Nations. We hope that in the United Nations, we will receive support from the Bandung group of states, from neutral countries, and even from the East. We do not believe that we would receive help from South American countries, but these countries would not be able to oppose this support head-on.

JBT: Who is your representative in the United Nations?

ECG: He is a representative of the old orthodox party. We need to change that because he is very bad.

Comrade Popović: Will you replace him?

ECG: We will. It is necessary that we have a stronger person in the United Nations, who will work actively and enter into relations with the representatives of the countries that are fighting for their independence. When Fidel Castro received a Medal of Honor from the Algerians, he said that two things were important to him then: one, that he received a Medal of Honor from the Algerians, and second, that on the same day, he was attacked by the Time magazine.

JBT: Time is always the first to respond on the side of reaction.

[…]

JBT: How is the situation with the armed forces in Cuba? Do they have modern weapons?

ECG: We have light modern weapons of North American origin, launchers, bazookas, some mines and machine guns of Belgian origin. We have no anti-aircraft defences, aviation, and even fewer airmen.

Comrade Mates: It is more difficult to be without aviators than without planes because planes can be bought.

ECG: The aviators mostly defected from Cuba because almost all of them were with Batista's regime. There are very few left.

JBT: It is very important that you have a solid army, morally and politically strengthened, so that in the event of a conflict, it would not defect to the other side... The conditions for aggression against Cuba are not so easy, however, because it is an island.

JBT: An invasion is not that dangerous for Cuba because it would be a major aggression. An airborne landing would be far more dangerous. It could be carried out with just several planes.

ECG: A landing could only come from the USA. But we are not afraid of such actions because we have unity in the country, especially among the peasants.

JBT: That is very important.

ECG: Paratroopers who would land in Cuba do not know the terrain. They would not be able to go further than the landing site because the peasants would attack them. They would have to turn against the peasants and thus be quickly disabled.

Narciso Fernandez Camizares: A well-known US tactic is to rely on the armed forces of other South American countries. However, Cuba has a solid army, which grew up in the revolution, and which is unique, like the people themselves. Events similar to those in Guatemala cannot occur in Cuba because the army is on the side of the revolution.

JBT: That is why it is important to keep the peasantry on your side. In order to achieve this, you should proceed with the implementation of agrarian reform because it is the basic driving force for the consolidation and further development of the revolution. We wish you much success in overcoming all the difficulties you have. Our people have sympathy for all people who are fighting for independence. If you preserve unity in the country and have a strong and well-armed military, even if it is not large, it will be difficult to do anything from the outside. Yugoslavia was almost in a worse position. During the war, we fought against Hitler's Germany, the greatest power that had enslaved the whole of Europe, and also against Italy, Bulgarian and Hungarian fascists and internal quislings. The quislings themselves were initially outnumbering us.

ECG: We became acquainted with the various stages of your great struggle. We were also in the museum in Belgrade. We consider your victory in the war to be truly epic. We are happy that our revolution cost only 20,000 lives. That is why we can also understand the magnitude of the victims among the Yugoslav people, who lost 20,000 people in just one battle. We also know that your wish for us to be successful is not just a matter of courtesy because we saw during our trip to Yugoslavia that we enjoy sincere sympathy with your people. Yugoslavia has already solved many problems, and we understand the importance of your successes and experience. We will try to convey them to our people in the best way possible. In foreign policy, we will strive to follow non-aligned positions — the policy of neutrality — together with nations that follow their own independent paths.

JBT: If you need help and support from the United Nations, you can count on it. We will certainly support you, as we support all nations fighting for independence. How are the economic relations between Cuba and Yugoslavia?

Grgur Cviličević: They do not have direct instructions from their government in this regard.

ECG: Yes, it was not included at the beginning of our journey, and we did not have the possibility to negotiate on this issue. We are doing everything to establish as many contacts as possible so that we can provide our government with the most complete information possible.

Comrade Mates: Our Goodwill Mission initiated discussions in Cuba about purchasing 140,000 tons of sugar, which later continued through the Washington embassy.

ECG: We talked about it with the Undersecretary of State Velebit. He told us the proposal should be revised, given that Yugoslavia will have an extraordinarily rich harvest of sugar beets. He suggested that this amount be reduced, that is, that your proposal is made more concrete so that it corresponds to the current possibilities.

JBT: Did they ask any other questions?

Comrade Mates: They have a general interest in all issues.

JBT: Will he visit anything else in Yugoslavia?

Grgur Cviličević: He will visit Rijeka and the "Treći Maj" shipyard. They are interested in buying boats and electrical household appliances. He will visit "Litostroj" in Ljubljana.

JBT: There are more factories for household electrical appliances in Yugoslavia.

Comrade Mates: It is best that they visit Maribor.

ECG: We are also interested in tractor and agricultural machinery factories.

JBT: We could see such a factory in Osijek.

Comrade Popović: They cannot see all the factories.

ECG: I see a great possibility for us to buy generators in your country.

Grgur Cviličević: They visited the Rade Končar factory, and the approximate prices they received at the factory seem compatible to them.

JBT: In Zagreb, there is also a company called Goran, which produces household appliances.

Comrade Mates: Our Mission of Good Will proposed to establish chargé d'affaires, if not embassies, in the capitals of Yugoslavia and Cuba.

JBT: Where do you have an embassy nearby?

ECG: We had embassies everywhere where life was good. I apologize for our government's relations with Yugoslavia. It is a bit difficult to explain, but there was a certain fear of Yugoslavia as a socialist country.

JBT: ... better to say Communist!

ECG: I can assure you that as soon as I come to Cuba, I will work to open a representative office in Belgrade, with an ambassador, or chargé d'affaires at first.

Comrade Gošnjak: Do they stay longer in our country?

Grgur Cviličević: On August 21, they will travel to Cairo, where they will stay only one day, and continue their journey to Sudan.

Comrade Gošnjak: I asked that because I assume, since they are still soldiers, that they might be interested in seeing some of our units, schools, etc.

ECG: In Belgrade, we already have an agreed contact and short talks with some comrades from the army. Otherwise, our time is very limited.

Grgur Cviličević: They were at the place where the Fourth enemy offensive was conducted. One of our majors explained very well the operations at that time, and since they are good soldiers, they took a lot of interest.

ECG: We are interested in sending a certain number of people who would be educated in Yugoslavia. Only, I think it's a matter of language because our peasants barely know how to read and write.

Comrade Mates: So far, learning our language has not been a serious problem. Students from Asia and Africa quickly mastered it.

JBT: Sudanese, Indonesians and others are educated in our schools.

ECG: Old people cannot go to school. After all, in our struggle, we had one old man who was 65 years old. In India, I talked to Krishna Menon about establishing relations, and he told me to send a professor or a doctor to India as our representative. I laughed and asked - what kind of professor, even when we don't have one.