In the 1970s, the countries of the South mounted a collective assault on the world economic order. They proposed, instead, a New International Economic Order (NIEO) to challenge the neocolonial system. Such a project painted the future sky with dazzling plans for prosperity, a bright variety of socialist and radical-nationalist projects to change the world, and aimed to fill the carapace of political decolonization and the costly acquisition of formal state sovereignty with economic decolonization.

It is increasingly common to ask about the origins of this project. I want to pose the question slightly differently: what kind of world made such world-making possible? A second question: what were its strengths and what were its weaknesses? A third question: why could it not be tolerated by the imperialist powers? And a fourth: what can we use to build upon it today?

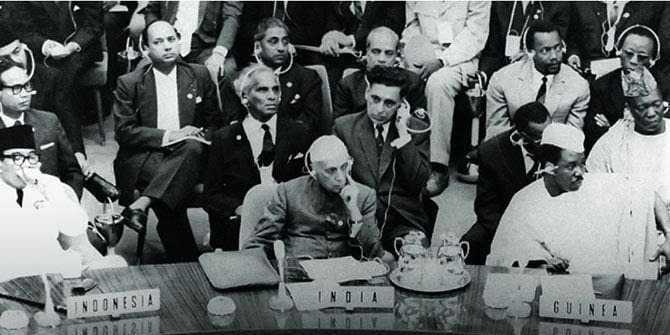

The NIEO was the fruit of the two great anti-systemic processes of the 20th century: socialist construction in the Soviet Union and China, and national liberation movements – often armed, emboldened, and ideologically colored by socialism and communism. Against this background, liberated states – eventually building common fronts with radicalized Latin American states – and Cuba, increasingly the lodestar, began to converge in a constellation of organizations which moved from strength to strength: the Bandung Conference, the Afro-Asian People’s Solidarity Organization, the Non-Aligned Movement, and the Tricontinental.

Such meetings had distinct ideological colorations with different but overlapping participants and goals: from Bandung-era interest in economic development and cooperation, and self-determination; to the NAM’s wish to avoid hot wars and coups burning across its member countries; to the Tricontinental’s increasing unity around anti-imperialism and national liberation.

The movements were complemented with radical critiques of the existing system: Amilcar Cabral1 and Mehdi Ben Barka’s2 theories of neocolonialism, Latin American structuralism, then Samir Amin’s3 dependency theory. And they began to wrest control of international institutions and build counter-forces within them (the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, for example). It was against the background of surging socialist construction, alongside ongoing neocolonialism – cheap Northern imports of oil, coffee, and cacao – that the NIEO emerged as a revolt against prevailing terms of trade and of unequal exchange, which the countries of the South saw as looting their national wealth.

The strengths of this project were numerous. One, an explicit challenge to the terms of economic order, de-naturalizing the price system as a legitimate matrix by which to allocate wealth and poverty. Two, the unity of large numbers of the countries of the South, all absolutely necessary for rupture with the established order. Three, a rising discourse of self-reliance, questioning the automaticity of integration into the world economic system as it stood. Four, the leveraging of political decolonization into bids for economic decolonization.

The weaknesses were two-fold. On the one hand, they sought to challenge the terms but not the nature of the world economic system. They were against the imperialist political architecture of capitalism. Yet, some sought to build self-reliant national capitalisms, while others had a socialist orientation. They wanted self-reliance — often collective self-reliance — without a shared notion of the system they sought to erect in place of the one they wished to dismantle.

The second weakness was that the front, within which Third World oil producers were central, was necessarily a fusion of parts which could not but break apart: other than tremendous oil wealth, post-national liberation states like Algeria had little in common with imperial sheriffs like Saudi Arabia.

Such a front was brittle, and its joinings easily shattered.

Western states were eager to draw the South into fruitless convenings shorn of serious commitments, and to throw up endless smokescreens to divert discussion of development and underdevelopment to technocratic nostrums around basic needs.

If the front was not radical enough to win, it was too radical for the imperialist powers. If national capitalisms in the periphery were not possible because of the nature of accumulation on a world scale, which demanded subordination, labor reserves, and value transfer, and relied on peripheral disarticulation for markets and commodities, it was far too radical from the perspective of northern monopoly capital. Why, after all, would northern monopoly capital accept changing terms of trade which were to its advantage? Why would it allow for draining labor reservoirs which depressed peripheral wages and were central to the systemic stability of capitalism? Why would it allow peripheral sovereign industrialization when there were so many gains to be secured from disarticulated industrialization, subcontracting, and other modes of turning southern industrialization into labor arbitrage?

So, what lessons can be drawn?

It is useful to juxtapose the lessons that can be drawn from the lessons which are being drawn. On the one hand, proposals for various forms of global Green Keynesian policies abound, including focus on supply-chain justice in the form of changes in global terms of trade; breaking peripheral fiscal straightjackets to allow for anti-cyclical spending; even some belated and inadequate attention to fiscal transfers from North to South, reversing centuries of colonial and neo-colonial looting.

In principle the policies themselves would make (some) human lives better. However, policies are being seized upon without an analysis of the social context which made those policies possible: the existence of actually-existing attempts as socialist construction, which, as with all attempts by humans to change the world, were marked with flaws, and could not be otherwise. These policies, essentially attempts to make peripheral capitalism tolerable and developmentalist, not only faced savage opposition from the imperial core, but foundered on internal contradictions: domestic super-exploitation was intimately connected to neo-colonialism: unequal agrarian structures and massive labor reservoirs benefited domestic and foreign capitalists in equal measure.

Furthermore, these ideas developed in a fertile international environment, where movements newly taking state power continually advanced the global class struggle. Contemporary resurrection of those proposals, absent any analysis of the social context which made them possible, is deeply mistaken if not actively confusing and confused. They are not models to be copied, but history from which we can learn.

What can we learn?

One: national liberation remains the necessary framework to interpret peripheral (eco)-development. In a world structured by nation-states, nation-states remain necessary carapaces to shield popular development, to protect social movements from external counter-revolution, and to orchestrate or provide political, fiscal, and, if necessary, military architecture for popular development.

Two: popular development will not be built by states alone, but states in dialogic interaction with semi-autonomous or autonomous social movements. The people are the keepers of the keys.

Three: contemporary bids for national capitalisms with aspects of accumulation from below, capitalist land-to-the-tiller agrarian reforms, or non-socialist liberation movements in states colonized or aggressed by the imperialist core need principled support. Constructing a new world is a battlefield, and those who wish to win need to support advances as they occur, rather than holding them up to the standard of a perfect revolution that no struggle will ever meet.

But four: the fundamental orientation of the struggle to forge a new NIEO, a new Bandung,4 or a new Tricontinental cannot be left in ideological uncertainty. Capitalist developmentalism in the periphery is and proved to be a chimera and in the core has been a nightmare.

Production of goods under the law of generalized commodity production, accumulation of value, and for exchange value cannot deliver a decent world. Capitalism cannot be reformed. There must be a shared horizon of production of goods and services for use, with prices engineered to achieve a world-wide just distribution of these goods, social rights guaranteed, and political institutions created to allow for the human reproduction of the ecology. There must be appropriate and ecologically modulated sovereign industrialization alongside regional collective self-reliance.

Venezuela’s communes must be supported. The US war on Yemen must end. Campaigns against the sanctions hammering Venezuela, Iran, and Zimbabwe must succeed. The US terror lists, meant to isolate, criminalize, and mop up remaining national liberation armed forces, must be abolished. Caribbean demands for reparations must take center-stage.

Are these transformations possible in the current context? Yes and no. We are in a state of permanent insurrection. In times like these, the task is to rise to the challenge posed by capitalism’s structural incapacity to guarantee the social reproduction of most of humanity, and to be as radical as reality demands, rather than diluting any such radicalism in calls for pragmatism to reach a future which pragmatism has never and could never achieve.

Max Ajl is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Ghent and an associated researcher at the Tunisian Observatory for Food Sovereignty and the Environment.