In November 1979, U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Ronald Spiers urged Congress not to cut American funding for the Turkish military.

His request was unremarkable at the time. Strategically located on the Mediterranean and sharing a land border with the Soviet Union, Turkey had been a member of NATO for nearly 30 years and functioned as a key front-line state in American Cold War strategy. The United States built close relationships with Turkish security and intelligence services to achieve its goals, strengthening them at the expense of elected civilian authorities.

The International Military Education and Training (IMET) program, a security assistance program that paid for foreign military personnel to train in the United States alongside their American counterparts, was one element of that strategy.

Spiers saw IMET aid as an investment worth writing home about. The program “inevitably results in a very large return for the relatively small amounts expended,” he said.

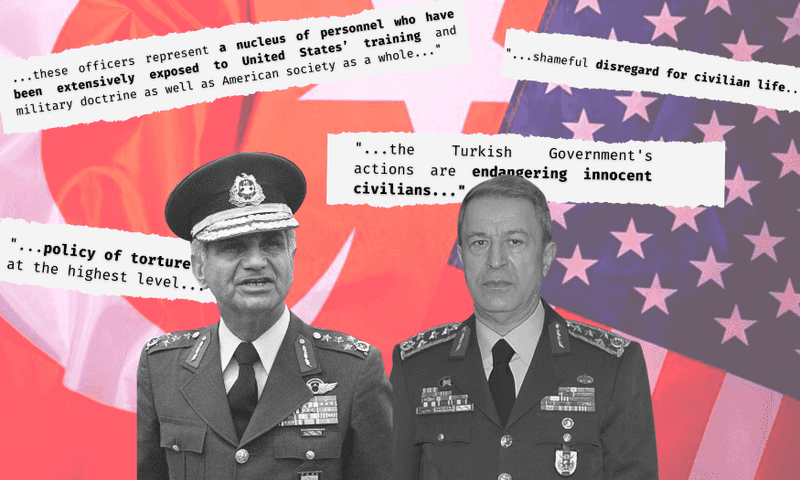

As an example, he named several high-ranking Turkish officers who had been “trained in the United States under IMET auspices:” Necdet Üruğ, Selahattin Demircioglu, Bedrettin Demirel, Tahsin Sahinkaya, and Nejat Tumer. Spiers described them as a “nucleus of personnel who have been extensively exposed to United States' training and military doctrine as well as American society as a whole.”

The return on American investment in the careers of this pro-Western ‘nucleus’ would come less than a year later. On September 12, 1980, all five men participated in the violent overthrow of Turkey’s elected government—ushering in an era of brutal political repression and endless war that would shape Turkish politics for decades to come.

Tahsin Sahinkaya, commander of the Turkish Air Force, and Nejat Tumer, commander of the Turkish Navy, were among the leaders of the coup and members of the National Security Council that ruled by decree for three years afterward. In 2014, a Turkish court found Sahinkaya guilty of crimes against the state, alongside coup leader Kenan Evren.

Necdet Üruğ, commander of the 1st Army, was responsible for the martial law command in Istanbul in the aftermath of the coup. He became Chief of the General Staff in 1983, a position he held until 1987.

Bedrettin Demirel, commander of the 2nd Army, was responsible for the martial law command in the provinces of Konya, Niğde, Kayseri, Nevşehir, Kırşehir, and Yozgat. Selahattin Demircioglu, commander of the 3rd Army, was responsible for the martial law command in the provinces of Erzincan, Gümüşhane, Giresun, Trabzon, Rize, Ordu, Sivas, Tokat, Amasya, Çorum, Samsun, and Sinop.

The 1980 Coup and the War in Kurdistan

The alleged role of the United States in military coups in Turkey has been discussed at length. The Spiers cable, which was released by Wikileaks in 2016 but has not previously been reported on, establishes something new: a direct connection between US training and leaders in a military regime that sent Turkey barreling down an autocratic and violent trajectory it has not yet been able to escape.

The 1980 coup crushed what little democracy existed in Turkey. The country’s elected parliament and political parties were dissolved. Labor unions and civil society organizations were outlawed, and newspapers were banned from publishing. More than half a million people were arrested on politicized charges. Torture was so brutal and pervasive that Human Rights Watch described it as a crime against humanity. Hundreds of people were known to have died in prison, and the real number was likely much higher.

Kurds were hit the hardest. They had already been subjected to campaigns of outright ethnic cleansing beginning in the 1920s and 1930s. The coup regime sought to finish the job by denying Kurdish existence and criminalizing every expression of Kurdish identity.

Barred from all other avenues to demand basic rights and facing assimilation at gunpoint, some Kurds chose to fight back. The Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), founded by a group of university students in the late 1970s, began its armed struggle for Kurdish national liberation in 1984.

In response, the Turkish regime razed thousands of villages, displaced millions of civilians, imposed military rule on Kurdish-majority provinces, and oversaw a campaign of extrajudicial killings and enforced disappearances carried out by state forces and shadowy paramilitaries. The PKK’s calls for ceasefires never turned into substantial negotiations. Out of the first 22 pro-Kurdish MPs elected to parliament in 1991 to try to address Kurdish concerns peacefully within the Turkish political system, six were jailed during their term and one was shot dead.

Funding Repression

From Washington, the violence may simply have looked like the price of a Cold War victory. Turkey was far from the first country where graduates of U.S. military training programs went on to wage war on popular movements and commit atrocities against ethnic minorities, dissidents, and the left.

The IMET assistance that the Spiers cable claims benefitted Turkey’s coup plotters also bankrolled the infamous School of the Americas, where the U.S. trained military dictators and death squads that terrorized countries from Chile and Argentina to El Salvador and Honduras.

“U.S.-backed military dictatorships ruled most of Latin America throughout the 1970s…Flush with U.S. military assistance, the heads of these armed forces found themselves in a position to send large numbers of troops to the School…a mechanism for subsidizing the training of foreign soldiers, called the International Military Education and Training (IMET) program, facilitated the flow of soldiers to the SOA,” Lesley Gill writes in The School of the Americas: Military Training and Political Violence in the Americas.

One Congressional Research Service report claimed that “the majority” of personnel trained at the School of the Americas were “funded by International Military Education and Training (IMET) program funds, provided through foreign assistance legislation.”

The release of a list of names of SOA-educated personnel involved in gross human rights abuses and the revelation that training materials used at the institution advocated torture and extrajudicial killings prompted outrage in the 1990s. Protestors demanded the school’s closure and an end to military training programs and other forms of support for repressive regimes in Latin America. Members of Congress introduced legislation to cut funding to the School and called on the Clinton administration to shut it down.

IMET and Turkey Today

A similar reckoning with the role of U.S. military training in fueling the worst abuses of Turkey’s war on the Kurds has not yet occurred. But one may well be in order. Though the Cold War is over, the U.S. continues to support the most militarist and nationalist elements of the Turkish state—with little regard for the consequences.

Between 1950 and 2020, Turkey was the single largest recipient of IMET funds worldwide. The State Department allocated $220,650,000 to train Turkish personnel during that time period. In fiscal year 2004, Turkey received $5,000,000 in IMET assistance—the highest yearly total not only for Turkey, but for any IMET recipient during the 21st century.

Turkey’s approach to the Kurdish question has scarcely changed during that time. Though the PKK’s armed campaign, mass mobilizations by Kurdish civilians, and an embattled but tenacious civilian pro-Kurdish political tradition have made 80s-style denial of Kurdish existence impossible, the far-right Justice and Development Party (AKP) regime still sees the issue as a military problem with a military solution, much like its coup-era predecessors.

In the name of “fighting the PKK,” Turkey currently occupies swaths of territory in Iraq and Syria, carries out ethnic cleansing of Kurds, Yezidis, Assyrians, and other minorities, empowers jihadist militias, hinders the fight against ISIS, and jails tens of thousands of civilians on spurious “terror” charges, including democratically elected MPs and mayors from the progressive pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) and its predecessors.

U.S.-trained officials continue to lead these policies. A Department of Defense document created in or after 2018 to track IMET-trained officials who rose to positions of prominence in their home countries includes nearly 70 Turkish personnel. The first and highest-ranking Turkish official on the list is identifiable as Defense Minister Hulusi Akar, who is recorded as having trained in the United States between January and June of 1987.

Since taking over Turkey’s Ministry of Defense in 2018, Akar has overseen a particularly violent era of Turkish foreign policy: a devastating invasion and occupation of northeastern Syria, multiple attacks on Iraqi Kurdistan, and an escalating campaign of extrajudicial killings of Kurdish and Yezidi leaders in the fight against ISIS and the effort to stabilize their homelands.

In an ironic twist, both Akar and the Defense Ministry as a whole were sanctioned by the United States for “endangering innocent civilians” and “undermining the campaign to defeat ISIS” during the October 2019 invasion of the Syrian cities of Serekaniye and Tal Abyad.

Today, as Turkey launches a new military invasion of Iraqi Kurdistan and cracks down harder than ever on Kurdish and non-Kurdish political opposition alike, the State Department has requested $1,450,000 in IMET aid for the country for fiscal year 2023. Given the program’s track record, it is difficult to see this as anything other than an investment in dictatorship, endless war, and a military solution to the Kurdish question—failed policies that have brought nothing but death and destruction to the region.

Meghan Bodette is the Director of Research at the Kurdish Peace Institute.