Samkharadze has silver hair, faded tattoos on his forearms, and heads the Trade Union of Mining, Metallurgy and Chemical Industry Workers of Georgia (TUMMCIWG) in Chiatura. Tragically, deadly accidents are all but typical in mining towns like this one, in Georgia’s lush and hilly Imereti region.

While Georgia’s status as a hip new travel destination for western Europeans has led to a tourism boom, the country’s mining sector is in stagnation. After years of neoliberal reforms that left unions weak and workers’ rights degraded, desperate wildcat strikes have become a frequent feature in the local miners’ struggle for survival. Chiatura and neighbouring Tqibuli, where practically all households depend on the industry, have been particular flashpoints in recent years.

It was in the late 1800s that rich manganese deposits were discovered in the canyon walls enclosing Chiatura. When a young Joseph Stalin arrived there in 1905, to agitate among the miners, they were responsible for half the world’s manganese production. Back then, 18-hour shifts were the norm, and Chiatura soon became a Bolshevik stronghold. Under Stalin’s reign, many years later, the town experienced its heyday. An expansive network of cable cars was set up to facilitate the transportation of workers and ore between living quarters, mines and processing plants on both sides of the river.

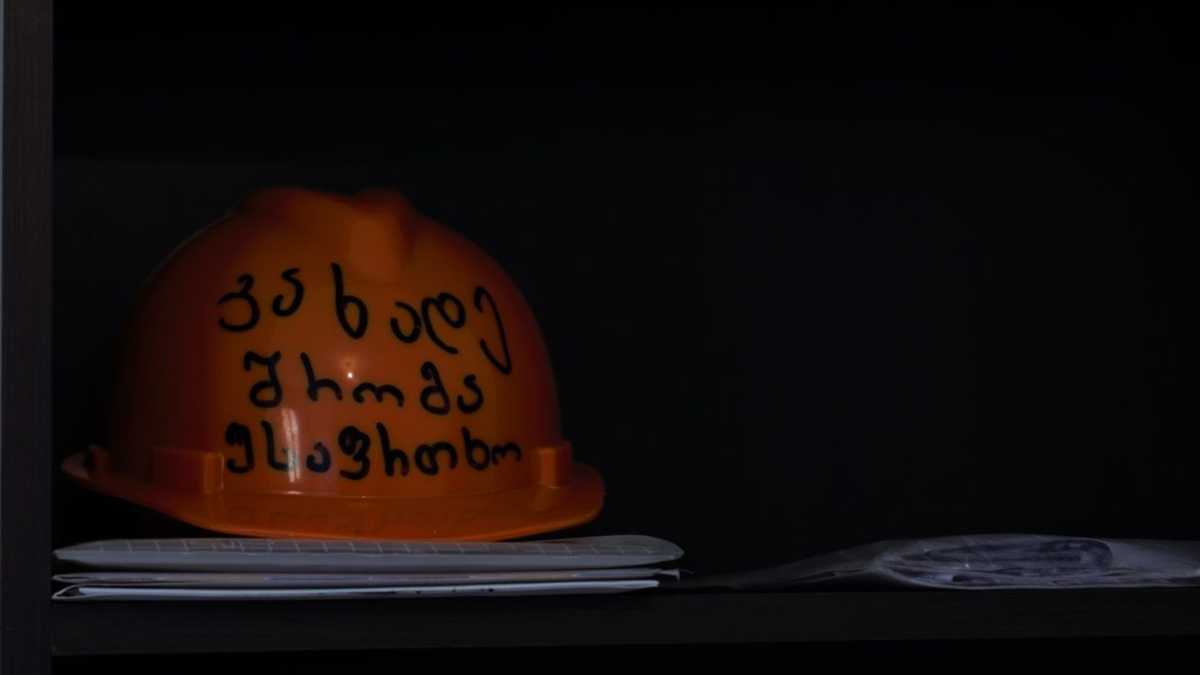

Much has changed since then. The mines are now operated by a Miami-based company called Georgian American Alloys (GAA). Most of the cable cars have stopped running, their gondolas suspended in midair. In terms of working conditions, the clock has been turned back as well. In 2016, GAA introduced a new schedule at several of its mines that entails 12-hour shifts, for 15 days in a row, during which workers are required to live in on-site dormitories. Management justified the new regime as a cost cutting measure, necessitated by the tough international competition.

“It’s crazy. Not even those with apartments just a short walk away are allowed to go home to their families,” union rep Samkharadze explains, “supposedly to prevent them from doing other work on the side”.

While Samkharadze’s union was opposed to the new system, it wasn’t able to muster any successful resistance.

In today’s Georgia, unions are notoriously weak. Though 90% of GAA’s roughly 3000 workers are union members, only 10% belong to Samkharadze’s organization, about as many to a company-controlled yellow union, and the rest to the surviving Soviet era union, which continues to focus mainly on handing out holiday resort vouchers and similar perks, rather than fighting for improved conditions. Although Samkharadze’s TUMMCIWG comes closest to being a proper union, they too are often sluggish in capitalising on the feisty sense of solidarity that mining communities like Chiatura are known for.

This became especially clear last May: A group of miners fed up with living conditions at their dorms, occupied Chiatura’s town square and initiated a hunger strike – without backing from any one of the three local unions. “The whole thing was spontaneous and illegal,” Samkharadze recalls with a hint of irritation and embarrassment.

After GAA-management responded with threats, things escalated further. Local shops stayed shut and thousands of townspeople marched through the streets to support the miners’ demands, and add some of their own, concerning the ore processing plants’ impact on the local air and water. Eventually GAA ended the standoff by promising better working conditions and new routines to minimise emissions.

Even though many in Chiatura remain skeptical toward the company’s promises, things seem more hopeful than they do in Tqibuli, a coal mining community a few hours west. That town’s post-war golden age seems even longer gone than Chiatura’s. Central Tqibuli, built by POW’s and thus vaguely reminiscent of provincial Germany, is partly abandoned today. Once bustling with life in multiple Soviet languages, brought here by the influx of miners from across the Soviet empire, it is today rare to hear anything but Georgian on the now much quieter streets. The football stadium, with a capacity of 18,000, could now accommodate the entire town’s population.

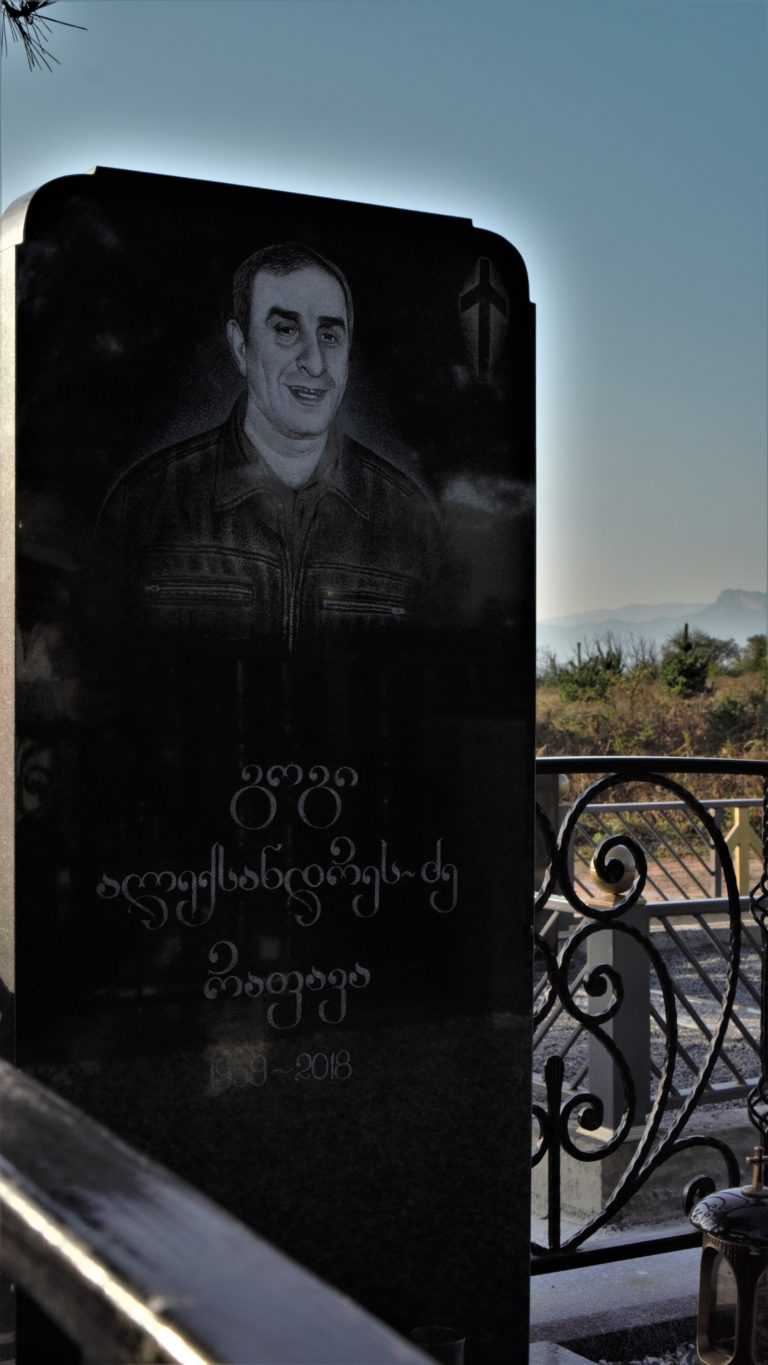

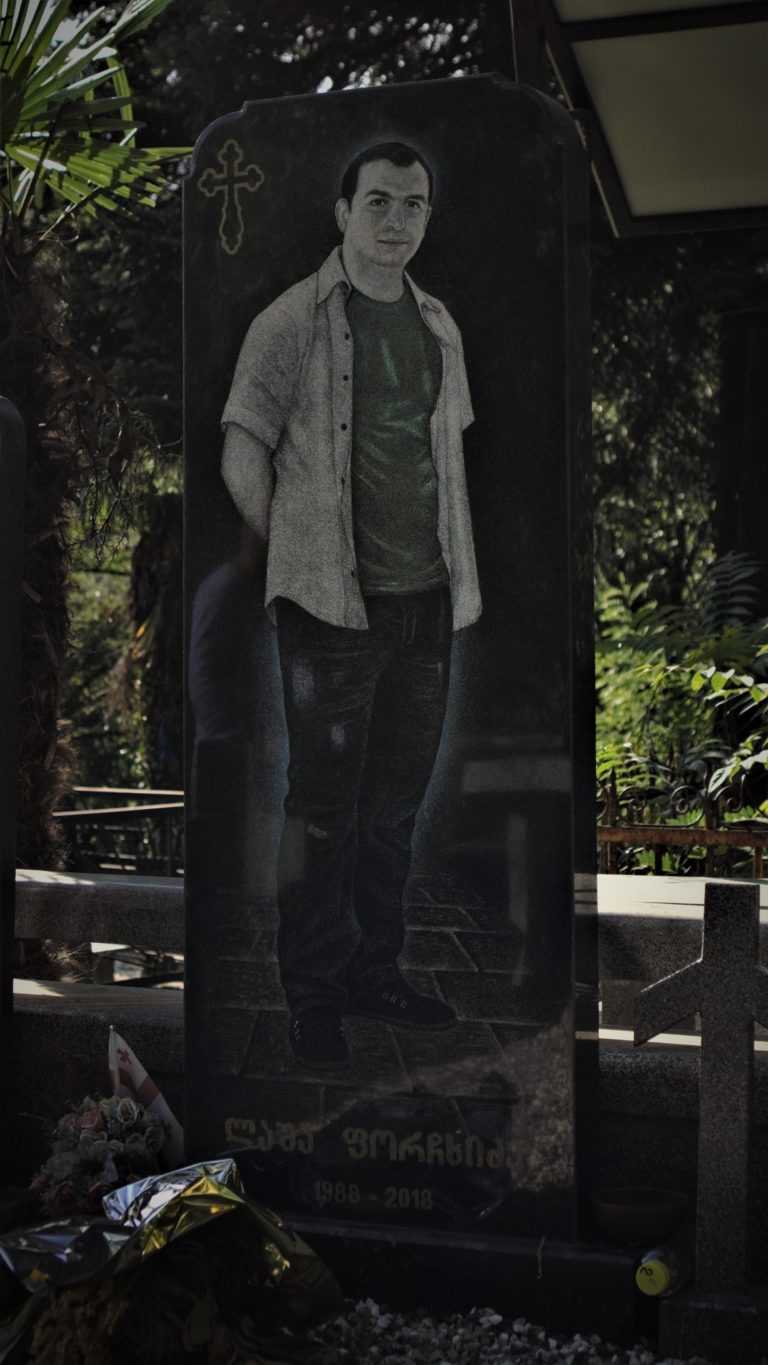

Tqibuli is dying with its mines, in more than one sense. With Georgian gravestones traditionally portraying the person buried beneath them, a walk through Tqibuli’s cemeteries means coming face to face with the many young men who have fallen victim to the mining industry’s deregulation. Men like Mirab Kolondadze, who was killed at 37, in an underground explosion one January night in 2011. “We were preparing the last blast of our shift”, his former colleague Vitaly Turdziladze recalls over a glass of sticky homemade plum vodka, sitting in his living room couch. “But everything blew up early.”

Turdziladze himself barely survived, with burns to 60% of his body. To this day, he has trouble making his scarred hand into a fist. He now lives on a disability pension of around £50 a month.

Like in Chiatura, miners in Tqibuli have repeatedly stood up against their deadly working conditions. During a 2016 wave of protest they even stormed the local offices of the mining company Saknakhshiri. But the dying continued, with 10 miners killed in 2018 alone. According to Gaga Isakadze, the local chair of TUMMCIWG, which unites 90% of Tqibuli’s roughly 1500 miners, aside from aging equipment, a key reason for the staggering fatality rate in the mines is performance-based pay. “You have to rush and ignore safety procedures to make a decent paycheck,” he explains.

If the situation in Chiatura and Tqibuli makes one thing clear, it is the human cost of Georgia’s push for neoliberal reform that peaked around a decade ago. Mikhail Saakashvili, the president at the time, abolished the labor inspection authority and curtailed various workers’ rights. Studies have shown that workplace fatalities nearly doubled after the reforms. A Human Rights Watch report looking at labor safety in Chiatura and Tqibuli, published this fall, concludes that lacking workers’ rights among miners is a key reason for the sector’s fatality rate. While the labor inspection office was restored in 2015, critics still consider it too weak to effectively ensure decent labor conditions.

It seems that until Georgian workers find ways to make their power felt more effectively, they may continue to pay for the country’s neoliberal experiment with their lives.

Volodya Vagner is a freelance journalist covering culture and politics.

Photo: Marco Fieber, Flickr