The commune and its people, the comuneros, sit at the center of the Bolivarian revolution — acting together, they alone are capable of delivering its emancipatory project of rupture. Embracing that vision, the Alexis Vive Patriotic Force began to construct the Commune as an anti-hegemonic force, a new model of living that would chisel away at the status quo. Through novel forms of production and strategies for self-sufficiency, the Commune would resist the unrelenting assault on the Venezuelan revolution and build a new world.

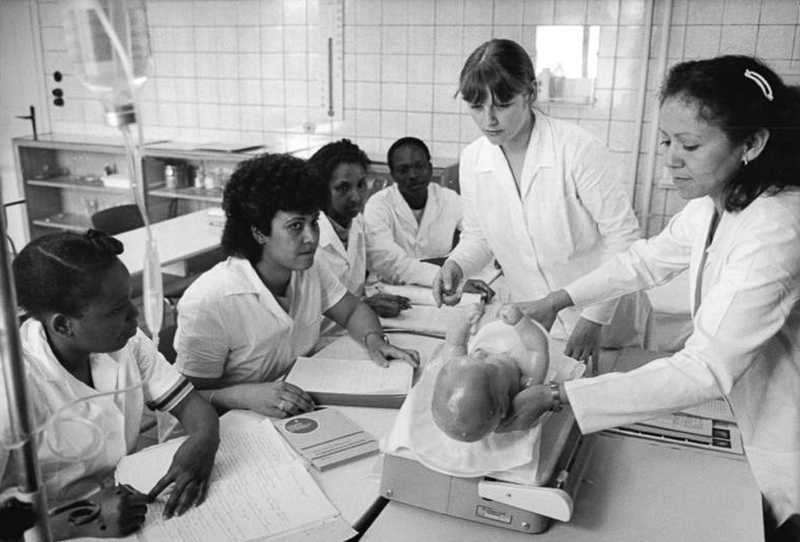

El Panal now houses 14,000 people. The comuneros have built their own schools, health services, community police, factory, and television and radio stations. The rent is free, and food is distributed door-to-door each day. Decisions are made through a communal council — a vibrant model of participatory democracy. Since the El Panal Commune was founded, the Venezuelan government passed legislation to support the formation of similar projects around the country. They now number in the thousands.

Like all nations in Latin America, Venezuela is in the midst of a protracted struggle for sovereignty. Last week, on 24 June, it commemorated the 200th anniversary of a landmark victory in the Venezuelan War of Independence: the Battle of Carabobo, where Simón Bolivar led South American patriots to victory over Spanish royalist forces. Five days later, Bolivar entered Caracas, from where he would mount further assaults against Spanish empire. These struggles for sovereignty would ultimately birth six Bolivarian states: Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, Peru and Venezuela.

The colonial power relations that sparked the Bolivarian revolutions two centuries ago continue to thread through the international system today. From unilateral sanctions to the rules of the World Trade Organization, the vaunted “international rules-based order” and the institutions that undergird it are little more than a codification of imperial dominance, carefully masked in legalese and appeals to democratisation. When the US asserted dominium over South America in 1823 in what became known as the Monroe Doctrine, Bolivar recognised that it was destined “to plague America with misery in the name of liberty.”

That misery runs deep. According to Alena Douhan, the UN Special Rapporteur on Negative Impact of Unilateral Coercive Measures on Human Rights, US sanctions have reduced Venezuela’s government revenue to 1% of its pre-sanctions level, underscoring the need for projects of popular sovereignty like the El Panal Commune. Now, the US is using the global economic and health system to weaponise a public health crisis. Venezuela is struggling to access vaccines, and Cuba is constrained in its ability to produce and deliver them.

Venezuela has long sought to build regional unity in South America as a bulwark against US influence in the region. Through initiatives like the Bolivarian Alliance for Peoples of Our America (ALBA), founded in 2004 by Hugo Chávez, it sought to advance regional integration through an intergovernmental system premised on social justice and sovereignty. In that spirit of collective resistance, the government of Venezuela convened two historic meetings last week, on the anniversary of the Battle of Carabobo, which I attended as a representative of the Progressive International.

The Bicentennial Congress of the Peoples of the World brought together some 500 delegates from 57 countries to chart a common agenda for movements around the globe. After three days and 27 working groups divided by geography and focus, the Congress agreed a Manifesto that includes declarations against vaccine apartheid, sanctions, and US militarism (the full manifesto is available here). It also includes a commitment to developing a global infrastructure for political education that would articulate the diverse agendas of Congress participants, and to strengthening the organisations and movements taking part, enabling them to implement the common proposals.

The ALBA-TCP Summit, held on 24 June at the Miraflores Palace, brought together the leaders of the ALBA nations — Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, Nicaragua, Dominica, Antigua and Barbuda, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Granada, and Saint Kitts and Nevis. In attendance were former Bolivian President Evo Morales and former Ecuadorian President (and PI Council member) Rafael Correa as well as participants of the Bicentennial Congress. As a vicious storm pummelled the Palace, the leaders of the ALBA governments spoke at length about the challenges they face to their nations' sovereignty. They adopted a 33-point Declaration, reaffirming their commitment to regional integration and unity in the face of escalating external attack, "to jointly face the attempts of imperialist domination and the growing threats to regional peace and stability".

The stakes of the struggle for sovereignty could not be clearer. The Cold War — here, cold only in name — revealed US empire to be no less brutal than its colonial forebears. Through anti-communist programmes like Operation Condor, the US-sponsored the extermination of hundreds of thousands of leftists across the continent.

The legacies of these policies exist in Brazil, where Jair Bolsonaro, heir to the US-backed military dictatorship of the 1980s, has turned the Covid-19 pandemic into a genocide. More than half a million Brazilians have lost their lives to the virus. They exist in Ecuador, where International Monetary Fund policies compelled the state to lay off nurses and other healthcare workers just before the pandemic. When Covid-19 struck, families would leave the bodies of their dead relatives in the streets because there was no one left to take them away. They exist in Colombia, where a US-backed dictatorship has exterminated scores of indigenous and social leaders in a prolonged campaign of repression that has taken an alarming turn in recent months.

But, from Bolivar to Chavez, revolutionary leaders have shown that it is possible to break away from the yoke of colonialism and imperialism. Their revolutions thrust open the window of political possibility, setting the stage for the long and arduous process of building a new world based on national sovereignty and international solidarity. Projects like the El Panal Commune show that this world — a sustainable, democratic, communal, and sovereign world — is possible.