Editorial note: The southern Italian town of Riace may be small, but during Domenico “Mimmo” Lucano’s spell as mayor it became known around the world for all the right reasons. During the postwar decades, inhabitants in this Calabrian town slumped from 2,500 to just 400, mostly because of locals emigrating in search of work. This trend was reversed under Mimmo’s leadership as, faced with increasing refugee arrivals on Southern Italian shores, Riace became known as a “model” of integration. Last year, however, Mimmo was sentenced to thirteen years and two months in jail for the crime of helping human beings in need. PI’s Wire team spoke to Mimmo about the ‘Riace model’, his persecution, his political ideals and why an Italian TV series about Riace was cancelled.

What is the ‘Riace model’?

The ‘Riace model’ is very simple. In Calabria, villages abandoned by emigration are known as ‘fragile areas’. Very few people remain in these inland villages and Riace was destined to end up like this – even my own children left. When the first Kurdish refugees arrived in 1998, we found ourselves in this situation and it felt natural to start hosting people – it was even suggested by one of the refugees who pointed out that these places are very similar to Kurdistan. He said “We would like to stay here in Riace”, he looked around, and then, after a silence, “Why don't we ask?” So that’s what I did, I spoke to the bishop, Mr Brigantini, who told me it was “prophetic intuition”.For me, this validation gave the issue a certain depth. Not only to the specific circumstance, meaning the arrival of people and the logistics involved, but at the level of political consciousness. I realised that the bishop and I shared a vision and beliefs in terms of social equality and fraternity.

This story was also born because the bishop thought it possible and it was born at a time when everyone here, including young people, was saying it was time to leave. This seemed to be the fate that would befall all the families in Riace but Mr Brigantini sparked hope and lit a light. This also gave me enthusiasm to go into local politics, not directly as mayor but as a town councillor at first. Later, I became mayor in 2004, in 2009 and 2014, making me a ‘protagonist’ while migratory flows into Italy simultaneously increased. Refugee reception policies and I crossed paths almost by chance. It really did feel like destiny.

Was crossing paths with Lega, Matteo Salvini’s political party, something that also seemed predestined?

This was not just Italy’s destiny, but that of Europe.

The problems arise from two schools of thought clashing in Riace. Salvini claims that I was careless as mayor. Now, Riace is a municipality of only 500 inhabitants, an insignificant number in a country as big as Italy, so why did he care? It is because the message of solidarity and community it conveyed was universal and has no borders. Even more so when the message is coming from a land that has almost nothing for its own and where everyone emigrates.

I am not a member of a political party and I have always thought that leftist radicalism is not intrinsically linked to the political party format. I feel being political is about more than elections because everything is political. It is a condition of society, of human relations and of the choices you make to help build something.

It would’ve been easier to tell the refugees to ‘go away’ but the bishop taught me that every person who comes through the door, every foreigner, can be a god. That's what we were taught – that’s the culture of ancient Magna Graecia, isn't it? Salvini accused me of being the mayor who “wants to colonise and fill these places with immigrants, with people from Africa”. But why the accusation and, what did he really want to say? He was really opposing the undertaking of such a political programme in a place impacted by emigration. In response I can only say that at some point during my tenure the issue of immigration became the driving force and mission of all local governance. Many of the projects involved local people who were out of work for example. There was hope and belief in an opportunity to improve the world.

Why did people take an interest in Riace, to the point of achieving international fame?

As I mentioned before, I believe that two ideologies clash in Riace. One revolves around brotherhood, solidarity and spontaneity, the other around egoism and the idea of ‘we come first’. But it is unacceptable to say ‘I come before another human being’. We all belong to the same earth and we all, in my opinion, have the same rights and hopes for the future. That’s why people are interested in Riace.

Could you tell us how the project was born and how the accusations against you came about?

The judicial problems started in 2016 but the story begins in 1998 when Kurdish refugees landed and a spontaneous refugee reception system arose in Riace. At that time I was not mayor but just a volunteer. I was talking to relatives in Buenos Aires and North America trying to find empty houses and so, together, we created a reception centre in the depopulated village. This is how Riace was born, through the spontaneous reception system that came about before there were any official projects.

In 1999, I became a minority councillor in the Riace Town Hall. We founded the association Città Futura, through which we gave abandoned houses to refugees following the method seen in Stignano and other municipalities in the region. We were inspired by the writings of Tommaso Campanella, a Dominican friar who wrote the utopian work The City of the Sun. Riace is a hamlet of Stilo, the town where he was born. Campanella wrote “I was born to defeat three extreme evils: tyranny, sophistry and hypocrisy”, this is the idea from which Città Futura was born.

Then, in 2002, Italy launched a national call for projects to host refugees and asylum seekers promoted by the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Ministry of the Interior. As I was a councillor and had gained experience through hosting Kurdish refugees in ’98, I took charge of setting up a hosting system. My initial concern was the wellbeing of this land destined to disappear in desolation. My family’s fate and Riace’s as a whole had been sealed for decades. This was the starting point.

What did you try to do in Riace to welcome refugees that was different?

Italy attempted to create a national hosting system with Rome acting as the national reference point for the participating municipalities. I insisted on the municipality participating and, in July 2001, refugee reception in Riace officially began. The first three municipalities to participate in the Ministry of the Interior’s call for applications were Riace, Isola di Capo Rizzuto and Badolato. It is not a coincidence they are all from Calabria and already had a common history of refugee arrivals. Our innovation was showing that it was possible to provide refugees arriving here with the opportunity to participate in a project anchored in solidarity.

At that time, in addition to Kurds, the first groups of people from sub-Saharan Africa, mostly women from Eritrea and Ethiopia, started arriving. In 2004, I became mayor of Riace on the basis of my previous experience and then people started to become interested in what was going on in Riace. They had seen how tourists were coming there to work out how a small place in Calabria had become so supportive of refugees. It became like a tourist attraction: you could almost say that solidarity-tourism was born here in Riace.

When did your widespread electoral success begin?

Not in the 2004 election because there were four lists at that time. The second and third time round, in 2009 and 2014, things went better. In 2016, the American magazine Fortune included me in their list of ‘The World's 50 Greatest Leaders’, which made the story go around the world. They even wanted to make a TV series about Riace with actor Beppe Fiorello, which would have brought us a lot of attention, but immigration was also receiving a lot of attention around the same time. Private television stations were trying to foment a form of collective hysteria by depicting immigration as the real evil of Italian society that was preventing us from making progress.

Did they make the TV series?

The TV series was blocked. They made it but never aired it because Forza Italia Senator Gasparri requested its suspension. My lawyers, who are defending me free of charge and among them the former mayor of Milan, Giuliano Pisapia, claim that one of the objectives of building a judicial case against me was precisely to prevent this series from happening. So it was suspended pending the judicial process because they were worried about broadcasting a series showing a successful refugee hosting project on prime time to about seven to eight million Italians, who would see that the Riace model is possible.

What was the reason for this political and cultural persecution of the Riace model?

Do you understand what the Riace model is? It is widespread refugee hosting and integration where everyone has their own home. The debate is currentlycentred around the right to live in depopulated places, which makes it so trivial because immigration is obviously needed to revitalise these areas. Why do we keep houses closed and abandoned and what use are they if they eventually get destroyed when it rains inside and they get damaged by the wind.

That’s why I turn the question on its head: I am convinced that the right to have a home is a universal human right of all human beings. How can we imagine creating absurd places like shanty towns when we have empty houses? Also, providing widespread refugee hosting in places where people still belong to a rural culture creates spontaneous and solidarity relationships with their neighbours, which has been the case in Riace too. No particular part of Riace has been set aside for hosting people so the land belongs to everyone. Even I, as mayor, am but one of many citizens. How could I think that I should have something more for my own personal enrichment? I find it absurd.

Could you explain how the ‘bonuses’ – a kind of local currency you created to help refugees – worked?

The numbers of refugee arrivals in Italy continued to grow as migratory flows became more significant and more consistent. This was no different in Riace so we went from a single managing body, Città Futura, to having six to seven managing bodies. As mayor, it was a little more difficult, because it is not easy to provide a social value and maintain an ideal, particularly when our societies are all structured around profit. We wanted to make sure that refugees had something but the Ministry’s programmes were always late in sending the funds for refugee hosting projects. That’s why I created the bonus system.

The bonus system was a copy of a project carried out at the Aspromonte Park in Calabria that set up a local currency called ‘Eur Aspromonte’. It was used mainly to promote tourism with a bureau de change where you bought these ‘Eur Aspromonti’ with real money. You were then entitled to a discount when spending them in the villages of the Aspromonte Park to stimulate the local economy.

We wanted to do something similar with the meal vouchers that were provided so I thought of giving them directly to the refugees so they could buy what they wanted. Each refugee received €200 and the project worked well because we gave them freedom. It was an innovation but everyone was scandalised – jurists and university professors all started investigating my life but all they found was continuity in the ideal of solidarity underpinning the projects. It was not the work of a criminal mind but even so they sentenced me to 13 years and 2 months as if I had committed a murder.

So what factors do you think led you to having judicial problems?

At some point, the government implemented a policy of giving €35 per capita and per-diem for each refugee, an absurd decision made by bureaucrats. These projects cannot be limited to the initial phase of refugee reception, but must also try to foster integration programmes. My idea was to do both, the initial phase and the integration phase, with projects such as the work grants for refugees through the oil mill projects, the social farm, the craft workshops and the houses for welcoming tourists. But now they are accusing me of embezzling money while also stating that ‘the mayor has not had any personal enrichment from these projects, but there are administrative distractions and carelessness’. But this is not ture! A terrible misunderstanding has led to this disorder and, in my opinion, this disorder is also due to bureaucratic difficulties. Meanwhile, I have done nothing for myself or my personal enrichment – in fact in some senses I have weakened myself.

All the judges read the case papers and so did the prosecution that proposed a seven-year sentence. Still the judges doubled the sentence. The strange thing is that the heftiest sentence is for embezzlement despite the evidence provided by the Guardia di Finanza colonel transcripts that said: ‘No, this mayor hasn't touched any money, he doesn't have current accounts, he doesn't have any property, he doesn't have anything, the interceptions show that his only interest was pursuing an ideal of refugee hosting’. The things I did as mayor in Riace, like the oil mill or the social farm, only enriched the territory. But in the end they turned it into a criminal offence and even a supposed abuse of power because of the so-called long-term stays.

How do long-term stays and the charge of abuse of power come into the picture?

Long-term stays were established by the Ministry guidelines and dictated that refugees were to stay in reception centres for a maximum of six months. But this is an absurd system. First, the Ministry of the Interior asked me for help finding contacts and then abandoned me when it suited them. They told me there was a very high number of arrivals and nowhere to put people because the centre and the north of Italy did not want them. The prefect, Mario Morcone, promised he would help but he also left me when it suited him. Then, worst of all, they told me that I had to kick people out after six months despite calling me once in September to help with refugee allocations – the number of arrivals is at its highest at the end of the summer. In Riace, we could maintain the local high school with the children of the refugees who were arriving. Instead, they wanted me to follow the guidelines set by the bureaucrats and kick them out after six months. That is why I still say today ‘Why don't we all have an open discussion about this?’.

So it was a heavy clash between morality and legality? What impact did it have on children's right to education?

What are we supposed to do if they tell us we have to kick people out after six months when there is an increase in arrivals in September? Do we integrate them in the schools and then kick them out again in February, depriving them of their education?

Yes, there was some carelessness but it is important to note that I did not break the law. I don't believe that the law can just be ignored, but I do feel sorry for people who use this word ‘legality’. Everyone talks about legality, but legality is also the companion of political power: is apartheid legality? Was the Third Reich legality? Mussolini? Legality in this sense is a strategy of power. I am surprised that there are even third-sector organisations that also push this ‘legality’ narrative. Legality can mean being consistent with the status quo, with those in charge. Weren’t Salvini’s security decrees against refugees legality? Is Salvini right? Inhumanity can be legality. Many say ‘but then anyone can make their own legal code’. But this is not what happened in Riace. What I was trying to do annoyed them mainly because in their eyes the reception project had to be perfectly in line with the set guidelines. But obviously I can’t accept kicking children out of the territory and out of the school system so I have disregarded this with conviction.

How do you respond to the criticism that you used the refugee reception system for your own political gain?

I always ask people what they think I gained from this apart from respecting people, especially children. If anything I weakened myself as mayor. The misunderstanding comes from trying to create a system of widespread refugee hosting based on freedom by creating work grants, and also to foster a multi-ethnic community as a model of integration.

The state is absent in this region and there are no factories and industries like in the north of Italy. The reality here is one of welfarism and mafia domination. We don’t have much so we had to create workshops for all things social things out of necessity. Nothing here was private. This is the Riace model.

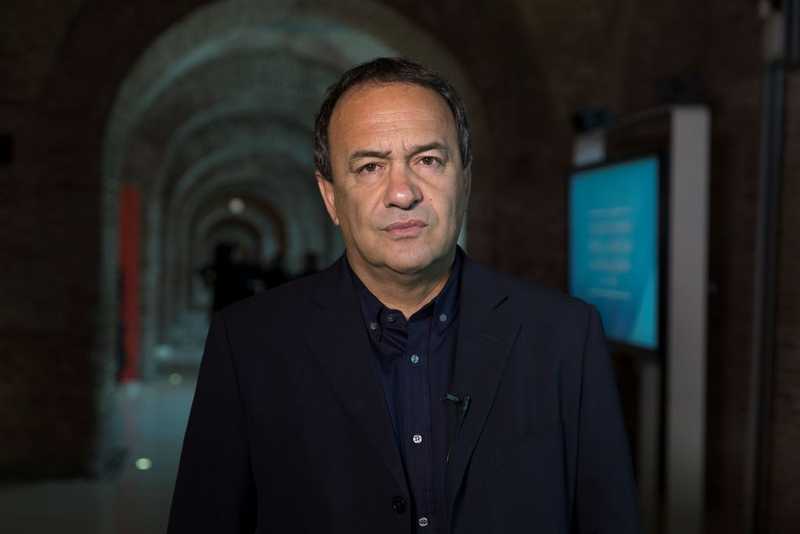

Photo: Flickr