Tanya Singh: Hi Saša, thank you for joining me today.

Saša Savanović: Hello, thank you for having me.

TS: Could you contextualize the recent student protests in Serbia for our readers? How have the protests impacted the political landscape in Serbia, particularly in terms of public opinion toward President Aleksandar Vucic and the ruling Serbian Progressive Party (SNS)?

SS: The newest in the series of crises striking the country in recent years was ignited after fifteen people lost their lives and two were severely wounded when the concrete awning of the recently renovated train station in Novi Sad collapsed. Government’s initial denial of any responsibility for the tragedy and utter lack of transparency concerning the station’s reconstruction, reheated the long-standing concerns over regime’s corruption and general disrepair and mismanagement of public infrastructure and services.

In response to the repeated physical assaults on protestors (many times by members/officials of SNS) and extreme policing (dozens were arrested, many beaten) students occupied large majority of the country’s university departments, demanding publication of all documentation pertaining to the station’s reconstruction; prosecution of those attacking protestors and dismissal of charges against those who protest; and a 20% increase of higher education budget.

Since then, the students are leading the protest with opposition parties taking the backseat (an important feature of the protests, keeping in mind that they enjoy little confidence). Although subjected to tremendous pressure, physically attacked, threatened and harassed by police, and targeted with vicious smear campaigns by the regime media, students continue to occupy their faculties, gaining ever greater public support: while protests they organize gather hundreds of thousands and wide support networks—providing students with logistical support and legal help, organizing preparation and distribution of food, hygiene products and similar—have been put in place.

The support is so overwhelming that it resulted in a general strike, or the closest possible resemblance of it. An extremely difficult endeavour since the regime controls more or less every public institution, including labour unions (while unionization in the private sector is practically impossible). An illustrative example is the education unions, which at first announced they’ll strike to give up on it after the government agreed to their terms. However, individual schools, hundreds of them, did join the strike, as well as national bar association, parts of EPS (the public power company), many cultural institutions and even small private businesses, while major streets of Belgrade and Novi Sad were blocked throughout the entire day. Day-long road and bridge blockades are announced for the days to come.

While there’s been no attempts to forcibly remove the students, the many and increasingly violent assaults on them that keep on occurring have led some commentators to describe the situation as “law intensity civil war”.

TS: In what ways have the protests highlighted or exposed broader issues within Serbia’s governance and infrastructure development, and what lessons can be drawn from these revelations?

SS: The current, students-led protests need to be looked at in the context of a wider anti-government atmosphere and the regime’s increasingly obvious authoritarian methods. The total capture of institutions and the media, deep-seated corruption, blatant election fraud comprise the commonly-cited repertoire of regime’s sins. Increasingly however, the regime is also denounced for its developmental approach which centres on foreign investment (supported by government subsidies), privatization of public infrastructure/services and stark deregulation. Besides the so-called investor-led urban development, there is a rising dissatisfaction with how the government is handling and in fact contributing to growing environmental degradation—for instance, air pollution in Serbia is so severe that many of Serbia’s cities regularly score among the top five most polluted cities in the world.

Most important of these controversial endeavours is Rio Tinto’s Jadar project, the proposed exploitation of the lithium/borate deposit found in the Jadar river valley in Serbia’s Mačva region. The resistance to the project—pointing out to grave environmental risks such as the release of toxic acids into the atmosphere, pollution of rivers and groundwater, the destruction of agriculture, as well as Rio Tinto’s terrible track-record, all of which far exceed potential economic benefits—started in 2019 and escalated in 2022 when the government caved in to public pressure and cancelled the project only to resurrect it again in 2024.

Thus, the protests engulfing Serbia should not be read simply as mobilizations against the present government and its corrupt, life-endangering, dubious deals, but also as an effort to challenge the neoliberal hegemony and question its maxim that profit comes before anything else.

What the tragedy in Novi Sad once again exposed is that the regime is not acting in the interest of the country’s people, but in its own interest and the interest of capital, no matter its origin (Chinese and local contractors in the case of the station, German auto industry in the case of Rio Tinto). All the while, the regime’s political opponents (opposition parties) do not offer any alternative political/economic vision, but simply imply that they will steal less and perhaps better regulate the machinery.

TS: In your opinion, what are the potential long-term implications of these protests for Serbia's political and social systems, especially regarding youth engagement and activism in the country?

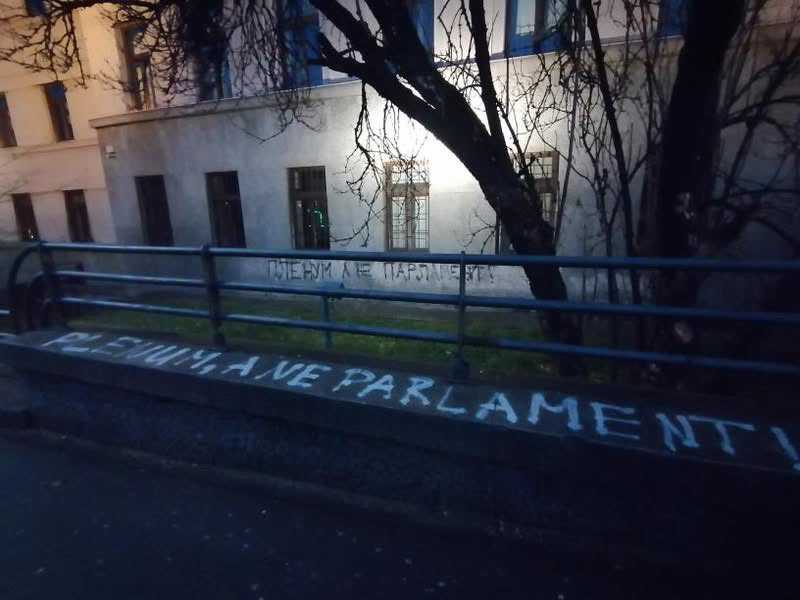

SS: The most important implication is certainly the political subjectivation and a grand entrance into politics by a generation that was previously considered anything but political. The ways in which their subjectivation plays out will ultimately determine Serbia’s future. What gives hope is that students have established their occupations through democratic self-governance, in the form of plenums, and that they continue to put forward principles of justice, freedom and solidarity.

The protests point out to the huge political vacuum left in the wake of liberal democracy’s collapse and the desperate need to formulate alternative societal and political imaginaries, which are lacking in Serbia as much as globally. The politics that saw the establishment of a functioning liberal democracy as its furthermost goal is entirely exhausted; not only that liberal democracy is on retreat before the superior forces of illiberal democracy, political capitalism, authoritarianism and similar, it is actually facilitating their rise, as mainstream parties keep sliding to the right.

The occupation of universities and their democratic organization, have also created a new political field, a new space and new means for the political to be enacted, going beyond the confines of the petrified institutionalized politics. The students have created what might be called a “disobedient institution”, partly within the system and partly outside of it, which proclaims its own political sovereignty, defines its own rules, pursues its own agendas. I think this is a huge event, especially in time when political and economic sovereignty of the nation state has become the thing of the past (at least for the peripheral ones such as Serbia). I see in it a potential for thinking and building new political institutions and a new organization of the political (imagine if the universities remained self-governed by their students even after the crisis has past).

TS: What role could international media and organizations play in highlighting the protesters' demands and the issues of corruption and governance in Serbia, potentially influencing both local and global responses?

SS: The fact that Western media is barely reporting on the events in Serbia, or portraying them in a highly distorted manner (as a conflict between pro-EU and pro-Russia/China forces, or even more idiotically as an introduction into a new Balkan war) is telling.

EU’s continued support to the regime, particularly its direct involvement in the Jadar project, demonstrates that the Union had given up on any pretence that its agenda is one of human rights, democracy and similar. Their policy towards Serbia has become brazenly colonial (no need to pretend anymore after Gaza). The only thing they see in Serbia is lithium.

Given this, the role of international media and organizations, those good-intentioned, is to stop reproducing orientalist stereotypes and actually understand what is happening. Secondly, their role is to place the struggle in Serbia within the global map of crisis hotspots, which challenge the status quo of undisguised imperialism and the “stability” provided by its adjacent comprador elites as well as the common wisdom that profit simply trumps all. As Columbia’s President Gustavo Petro said at the very start of Israel’s decimation of Gaza and its people: “The life of humanity, and especially of the peoples of the South, depends on how humanity chooses the path to overcome the climate crisis produced by the wealth of the North. Gaza is only the first experiment in considering us all disposable.” People in Serbia are waking up to the fact they too are disposable.

In their “Letter to students around the world”, students of Faculty of Dramatic Arts write: “The world is on the brink of collapse, representative democracy is failing and our future is at risk. (…) There are countless reasons for a blockade, and you know best what yours is.” While students call on their colleagues to join the blockades, their call certainly goes to all those who fight the same fight. Join in, do what you can.

Editorial note: At the time of first publishing this interview, we received information that Miloš Vučević, the Serbian Prime Minister, and Milan Djurić, the Mayor of Novi Sad, have both resigned from office.