In 1888, the “Russian flu” pandemic occurred. Thirty years later, in 1918, came the “Spanish flu”. Between these two dates, in 1893, the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch completed his masterpiece, The Scream. Munch wrote of his inspiration for creating it: “One afternoon I was strolling along. The city was on one side and the fjord on the other. I felt sick and tired. I stopped and looked out over the fjord — the sun was falling and the clouds were reddening in blood. I sensed a scream running through the wilderness; and then I heard a scream.”

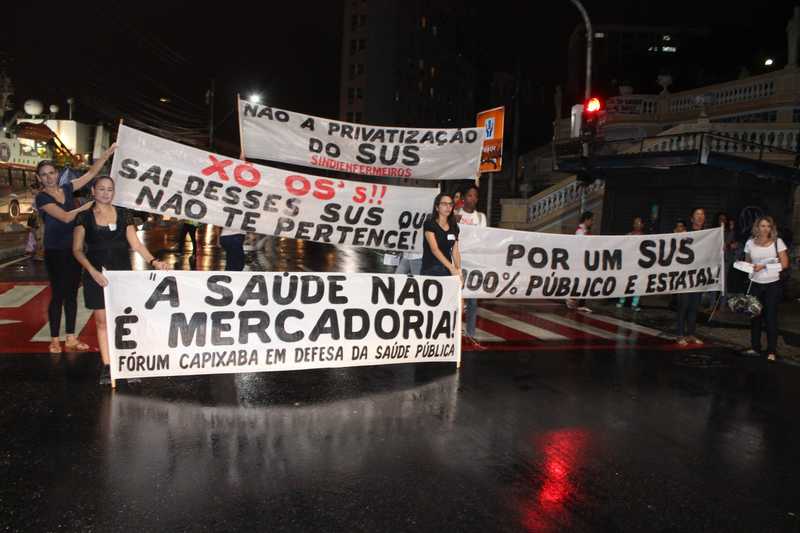

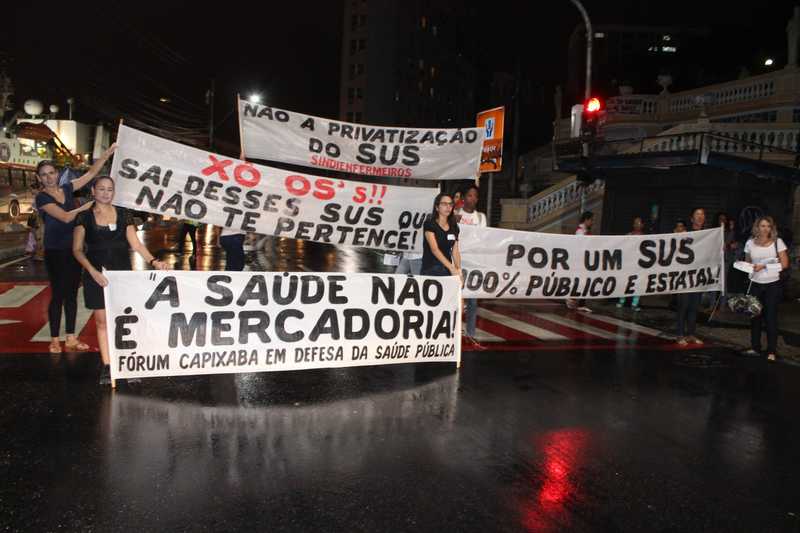

The Covid-19 pandemic, like all previous and future pandemics, will be remembered as personal, not collective; not as a historical disaster, but in millions of private and discrete tragedies. Munch's cry is an example of that collective suffering in an individual experience. In this sense, the State, as guarantor of human rights, must protect the collective experience and public health.

With this vision, Mexico, as pro tempore president of the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), asked the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) to draw up a plan for health self-sufficiency in the region. The plan points out that Latin America has been one of the areas hardest hit by the Covid-19 crisis. Despite representing 8.4% of the world's population, by the end of August 2021 it accounted for 20.1% of infections and 32% of deaths1.

Undoubtedly, the figures simplify the complex problematics of health systems in the region. But their compilation and analysis provide an opportunity to re-evaluate productive and technological capabilities, as well as to reformulate strategies and policies that encourage innovation in health systems.

When health regulation is discussed, it is generally seen as an instrument to solve market failures and an intervention mechanism to promote economic competitiveness. In a broader and multidisciplinary light, in this article we propose a new approach, one that promotes — in the field of health — the productive and technological capabilities of the region through the strengthening of health regulation. This would thus be understood not as a mercantile tool to be wielded in defense of capital, but also the economy, with a decisive impact on the drug supply chain. Regardless of the urgency generated by a pandemic reality, health regulation is one of the most mature responsibilities of the State, since people's health and eventually their lives are at stake. The absence of regulatory standards or their deficiency puts the safety of the population at risk.

The Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) has developed a tool to evaluate health regulatory capacities. It classifies national drug regulatory authorities (NRAs) into four categories, ranging from a non-existent level I to the highest, level IV, defined as the National Regulatory Authority competent and efficient in performing the recommended health regulatory functions to ensure the efficacy, safety and quality of medicines"2.

PAHO has evaluated 27 regulatory systems and only six countries in Latin America and the Caribbean meet the requirements for their NRAs to be designated as level IV. These are, in Argentina, the National Administration of Drugs, Food and Medical Technology (ANMAT); in Brazil, the National Health Surveillance Agency of the Ministry of Health (ANVISA); in Chile, the Public Health Institute (ISP); in Colombia, the National Institute for Drug and Food Surveillance (INVIMA); in Cuba, the Center for State Control of the Quality of Medicines, Equipment and Medical Devices of the Ministry of Public Health (CECMED); and in Mexico, the Federal Commission for Protection against Health Risks (COFEPRIS).

According to PAHO, the main functions of these entities are the registration (licensing) of products, inspection and licensing of manufacturers, inspection and licensing of distributors, post-marketing surveillance, regulation of claims that can be made for the commercial promotion of products, and authorization of clinical trials. Health regulation thus cuts across economic activity, the development of the health industry and also access to medical devices3.

What about countries with a lower level? Those that do not have a level IV have no capacity to authorize new products or drugs. This limits the entry of medical products into their market and, ultimately, their reach to the population in need.

In Latin America, inequity is systemic, but access to health supplies is an alarming phenomenon. The geopolitics of vaccines is, therefore, where our real sovereignty is at stake. Inequity in access to essential resources reveals a map of world power plagued by abuses, greed and injustice, but it also offers a path of cooperation to deploy our immense potential. Covid-19 showed the real dimension of sanitary regulation in Latin American and Caribbean countries and, in order to improve it, it is necessary to harmonize their technical decisions in order to boost production and scientific exchange in the region.

With a hint of utopia, and with the idea of moving towards a health system where all people everywhere have access to health supplies and services, we are talking about the construction of a Latin American Drug Agency. This agency would allow for the multilateral recognition of sanitary registrations and regional regulatory convergence among drug authorities. We would have a region in which — in the next pandemic, for example — a drug authorized in one country could, through a standardized procedure, be recognized in the rest of the region. This would decisively improve access to health supplies with the quality, safety and efficacy that we all deserve.

If Latin America and the Caribbean have six national regulatory authorities at level IV and they bear the entire burden of health authorizations and timely access to quality, effective and efficient drugs and vaccines in the region, let us take advantage of solidarity: in the event of health emergencies — when efficient and agile models of action are needed to provide medical supplies — this collaboration between sister nations through a Latin American Drug Regulatory Agency is essential. In order to generate those models of efficient action that strengthen our national health systems and our right to health in the region, we propose to break through on two fronts: first, to establish a critical path that generates tools and parameters in the region; second, to create a Regulatory School that begins with a program for the exchange of experiences.

Designing and establishing a critical path will be the detonator of the process that will lead us towards a Latin American Regulatory Agency that will facilitate access to health supplies. It consists of six essential steps that integrate communication, collaboration, trust, harmonization and regulatory convergence in the region, while improving drug and vaccine pharmacovigilance and decision-making:

- the establishment of a working group with all the regulatory authorities of Latin America and the Caribbean;

- the determination of all the indispensable criteria for countries with mature NRAs such as those of lower level;

- the identification of the necessary regional regulatory processes;

- the generation of agreements and their correct execution in each regulatory authority;

- the establishment of a package of tools towards a Latin American Regulatory Agency; and

- a convergence charter.

Establishing a convergence charter will improve the efficiency of resources, shorten timeframes and facilitate access to medicines and vaccines throughout the region. In the context of current (such as Covid-19) and future health emergencies, strengthening communication, coordination, harmonization and regulatory convergence is key to improving the health of our populations.

The second front we propose to open is the creation of a Regional School of Health Regulation. The professionalization of the knowledge generated in this sector is limited. In order to strengthen the capacities of the region's NRAs with an integral approach, it is necessary to broaden regulatory knowledge to include social dimensions such as education, employment, housing, food and the environment. At the same time, the aim is to reduce the structural deficit of human resources in health and reduce the gaps in access to education and training of specialists and professionals in the region.

Therefore, with a view to a future in which our region has highly trained personnel, the creation of a Regional School of Sanitary Regulation would contribute to the training of human resources with the capacity to carry out regulatory, control, surveillance and sanitary promotion activities with a comprehensive approach and excellence, for the benefit of human beings, the environment and the protection of sanitary risks derived from the products that are used and consumed.

Sharing experiences, achievements and common challenges is essential. This will allow us to expand our knowledge of sanitary regulation not only at the national level, but also as a region, in order to draw a regional diagnosis of the sanitary promotion and education capacity of the different NRAs, as well as diagnoses of each country on the academic level or subject of specialization of the workers of each NRA. We can also identify the knowledge gaps and broader capacities to begin with, as well as develop a program of institutional stays and exchanges between the different NRAs. In this Latin American spirit, implementing the latter program will strengthen the institutional capacities and efficiency of the different authorities and promote communication between counterpart agencies.

We propose these two parallel paths, the critical path and the creation of a Regional School of Health Regulation, based on what the recent experience of the Covid-19 pandemic has taught us. Mexico and Argentina joined forces to promote the first Latin American vaccine, which was possible thanks to regulatory alliances between the two countries: Argentina authorized the active substance and Mexico, taking advantage of the opportunity for industrial scale-up, approved the final product in its National Reference Laboratory. As a result, more than 100 million doses were distributed in all the countries of the region.

Health is an inherent right of the population and, at the same time, a strategic aspect for the productivity and well-being of our society. We may have to overcome resistance, both internally (our way of thinking) and externally (our way of living together), because we seek a stronger community, a stronger country, a stronger region through health regulation. When it comes to medicines and vaccines, we need an integral and sustainable paradigm. Comprehensive in the sense that it includes intellectual property rights, timely technology transfer and regulatory harmonization. And also sustainable, by applying financial instruments that provide incentives for research, development and innovation, that support long-term investments in local production and that ensure predictable demand.

We believe in protecting all our peoples from health risks through the technical and scientific strengthening of sanitary regulation. And we commit ourselves with conviction to fight against the indifference and inequity that overshadow our regional solidarity.

Alejandro Ernesto Svarch Pérez, Nemer Alexander Naime Sánchez-Henkel and Jorge Carlos Alcocer Varela. Respectively, head of the Federal Commission for Protection against Sanitary Risks (COFEPRIS); subdirector of Health Development at COFEPRIS; Mexico's Secretary of Health.

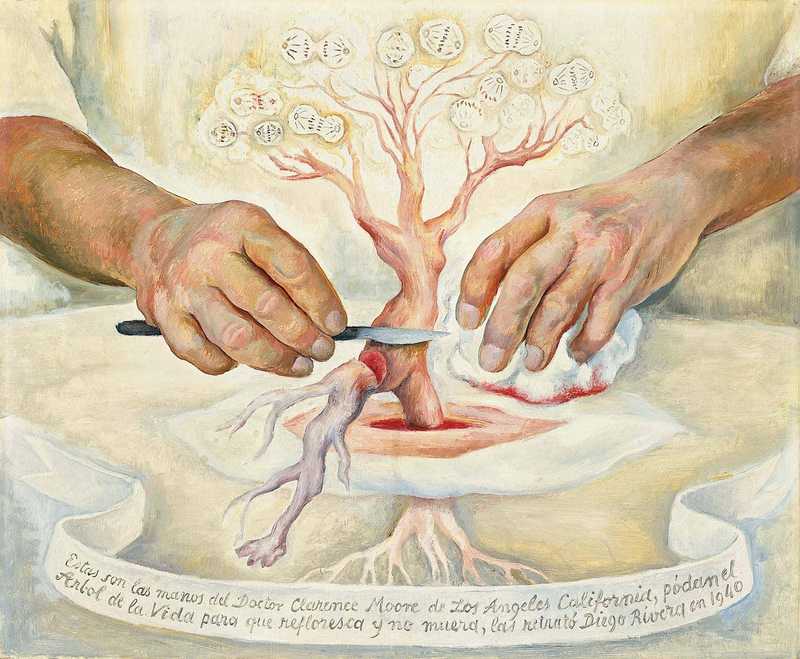

Image: The Hands of Dr. Moore, 1940, Diego Rivera