The headline of a recent World Bank press release comes across as very dramatic: “70% of 10-year-olds are now in learning poverty, unable to read and understand a simple text.” Learning poverty, as the headline suggests, is defined by the portion of 10-year-olds unable to read with basic comprehension skills. This figure, the report continues, has increased threefold worldwide, and it warns that we are facing the unprecedented challenge of a global learning crisis—rooted in the Global South—that is deep, widespread, and urgent. These things are all unequivocally true, but what the report fails to mention is that this crisis is anything but new. In fact, in sub-Saharan Africa, the effects of the pandemic have been much smaller than in other parts of the world, for no other reason than that learning poverty has been alarmingly high in the region since long before our pandemic days.

Doing a Google search of the “global learning crisis” will leave you believing that this pandemic-induced schooling crisis is costing countries catastrophic amounts of future productivity levels and, by default, of economic growth. The consultancy firm McKinsey & Co. published recent estimates of the toll that learning losses will have on schooling systems across the globe, contending that by 2040, the economic impact of pandemic-related education delays will be a staggering $1.6 trillion.

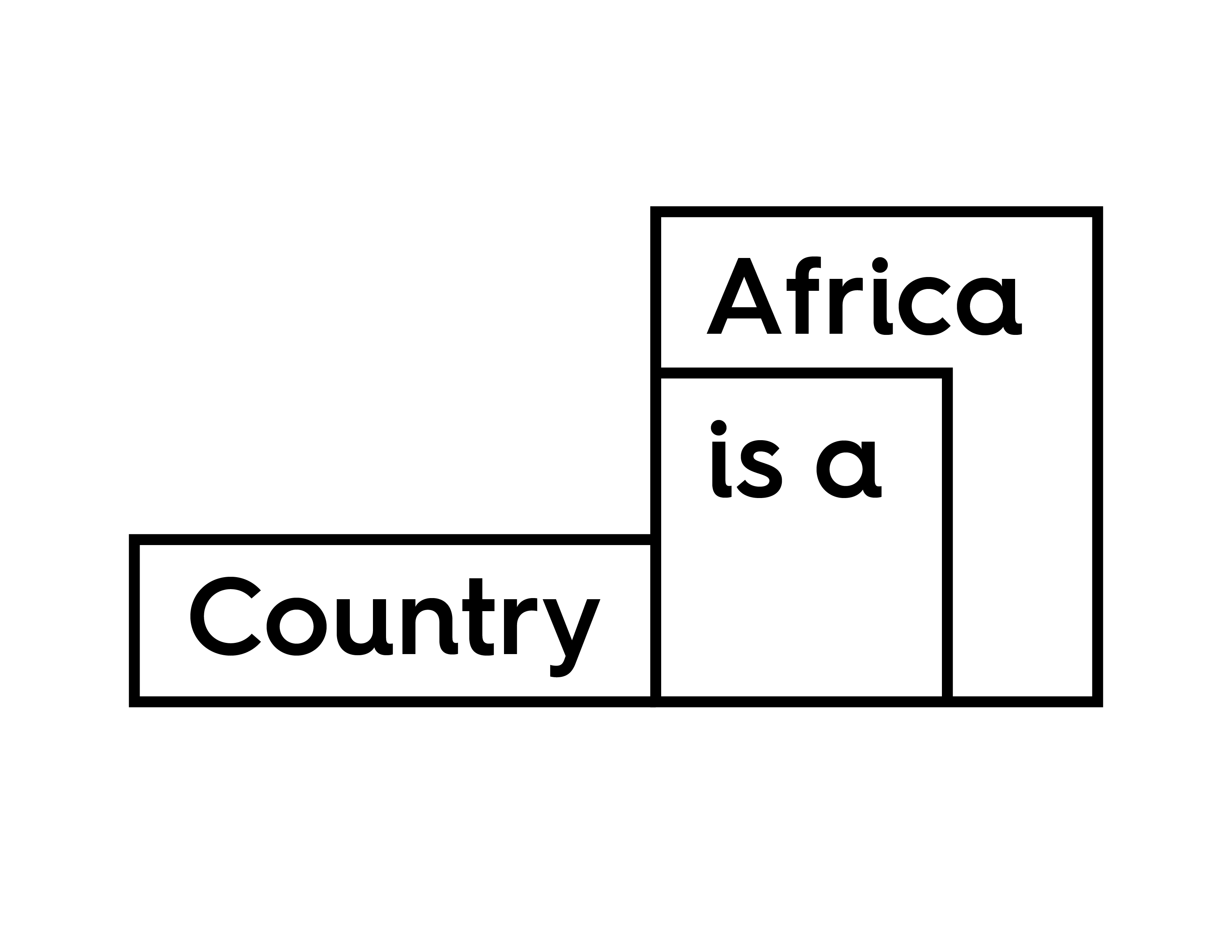

What both the World Bank report and the Google search fail to address in any substantial way is that education systems in many of the world’s poorest countries have been struggling with learning outcomes for decades, in no small part due to the pressures of an international education agenda that bends the schooling priorities of resource-constrained countries to its whims. The story of education in postcolonial Tanzania sheds light on the lesser-told—but hugely problematic—reality of how the global education elite have been eroding the quality of schooling for decades with their conditional aid and imposed neoliberal policies.

When Tanzania gained independence in 1961, it did so with the poorest learning levels of any of the ex-British colonies. At least 85% of its population was illiterate, making universal basic education a priority for its socialist government. By the late 1970s, the country had made great progress in both access and learning attainment, with illiteracy down to an impressive 10%. The 1980s and 1990s, however, were not kind decades for growing nations like Tanzania. The economic crisis caused by the Global North wreaked havoc on the struggling South, with hugely consequential effects for Tanzania’s long-run economic and educational development. Faced with severe fiscal shortages—in large part because it defaulted on previous loans—Tanzania took additional assistance from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. With these funds came significant conditions designed to liberalize the Tanzanian economy—including its education sector.

Schooling fees were introduced and education was turned into a for-profit enterprise, with immediate impacts on enrollments, dropout rates, and sector oversight capabilities. The learning losses were devastating. When the international community caught up to these effects, it overcompensated with a push for renewed commitments to universal primary education (UPE). Tanzania thus succumbed once more to the global order of education policy. Throughout the 2000s, it implemented a series of fee-free education policies meant to get all its children into schools. And that it did. But with it, an under-resourced system was flooded with new learners it wasn’t equipped to teach. With increasing enrollments came rising pupil-teacher ratios, fewer learning hours as classrooms were split into shifts, and countrywide textbook scarcity. The UPE push was so detrimental to learning in Tanzania that the colloquial term for it—its acronym pronunciation in Kiswahili, “oopay”—became synonymous with low-quality education.

The story of declining education quality in Tanzania is a decades-old reality. In Tanzania, learning poverty is well above the global average, but it is representative of a broader regional trend that has left over 77 million children scoring well below minimum proficiency learning levels. This is both an old story and a well-replicated one. In country after country across sub-Saharan Africa and the “developing” world, education systems were liberalized in the 1990s through imposed structural adjustment programs that slowly corroded any of the learning gains made in previous decades. COVID-19 learning losses have undeniably had an alarming effect in many countries—both rich and poor—but the greater, less talked about disaster is that this crisis has been brewing for years in countries like Tanzania that have, time and again, been stripped of the right to emancipated schooling agendas. If the cost of learning losses in the span of the pandemic is trillions in productivity (not to mention human and social well-being), how and when do we start measuring the losses accrued over decades of detrimental policies peddled by an international education elite that monopolizes not just the schooling agenda, but also the power to determine what is or is not a crisis?

Regina Guzman is a doctoral student at the University of Cambridge researching the former British education system in sub-Saharan Africa and in Tanzania specifically.

Photo: ICT4D.at / Flickr