As a Unite Scotland delegate on the Cuba Solidarity Campaign’s 2023 May Day Brigade, I spent 2 weeks visiting the island that — since Columbus first spotted its coastline aboard the Santa María in 1492 — has so attracted the wrath of the imperialists. Exactly two centuries after the Monroe Doctrine was first declared, however, Cuba continues to defy Washington’s laws of gravity.

This was my first visit to Cuba. My preconceptions had been shaped by Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s rich portraits of the revolution and Eduardo Galeano’s flowing prose. But our time in Cuba would dispel these romantic ideas while deepening my faith in the socialist mode of development.

‘Revolutions lose something with intimacy’, noted a 25-year-old Che Guevara when he first arrived in Jacobo Árbenz’s Guatemala in 1953 – mere months before United Fruit ordered the US-sponsored coup. This was undeniably true too of our brigade’s time in Cuba, but that was no bad thing. Misconceptions that the revolution had solved all of the island’s problems quickly vanished as the reality of the blockade became clear. Stepping out of the airport and onto our coaches, I noticed queues of cars crawling along the road. At their head was a petrol station with a singular operational pump. Fuel was in extremely short supply. The Trump administration’s 243 new sanctions, Cuba’s designation as a state sponsor of terrorism, falling imports from Venezuela and the impact of the pandemic on the tourist industry had left the island with only two-thirds of the fuel it required. “If the Cuban people are hungry, they will throw Castro out,” said President Eisenhower in 1960. Sixty three years later scarcity remains the US’ weapon of choice.

We were international delegates and well-accommodated but reminders of the stated US mission to “bring about desperation” were unavoidable. The difficulties of Cuban life weren’t hidden from us, far from it. “Truth is always revolutionary,” journalist Michel Enrique Torres Corona told our brigade. During our inaugural seminar, Gladys Hernandez, an economics professor at the University of Havana, explained the “unparalleled crisis” facing Cuba. The island was unique. It faced all the challenges of other developing nations in an erratic international system but with the additional imposition of a sixty-year blockade from its nearest neighbour, the most powerful state on Earth.

On the climate crisis, Hernandez was blunt. “Our people will drown if Cuba does not prepare,” she said. To brace for rising sea levels, the government has launched ‘Task Life’ to protect the 10% of land projected to be underwater by 2100.

We left that lecture hall with utopian conceptions of Cuban life a distant memory and a refreshed admiration for the resilience of the Cuban people. “This is a country that lives to enjoy life,” Hernandez had told us. “We do have problems, but we will never give up.” Over the next two weeks, everywhere we visited exhibited this resistance. We witnessed an alternative way of organising society which strove to offer dignity rather than strip it away. For centuries, Cuban resources had fueled profits in Europe and the United States as the engine of imperialism sweetened the oppressors’ tea. 1959 broke this cycle of dependence, putting the people in charge.

Cuba’s privatised pre-revolutionary agriculture ‘multiplied hungry mouths not bread,' wrote Galeano. In Havana, we spent three mornings working on the cooperative farms that today steer Cuba toward self-sufficiency. In the capital, urban gardens – Organoponicos – take up 10% of the cities’ land and have revolutionised sustainable agriculture. When Cuba was the world’s largest sugar producer, these same fields fed the development of industrial capitalism in the global north. Now, these gardens provide 60% of Havana’s fruit and vegetables. We were in the middle of the city but fields sprawled in all directions, eventually hemmed in by trees or hedgerows. Meagre though our efforts were, this example of how collective, under-resourced ingenuity not only alleviated but innovated is not something I’ll forget.

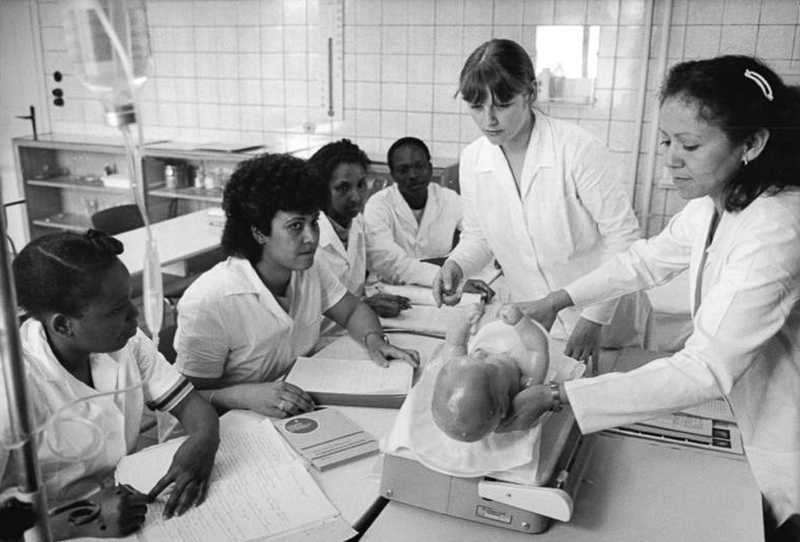

Revolutionary innovation extended well beyond agriculture. Our seminars took place at Havana’s Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology Center where against all odds Cuba had developed its own COVID-19 vaccines. While the US and Europe hoarded their stock, Cuba sent millions of doses to other developing nations. This wasn’t our last encounter with medical internationalism. While visiting a hospital in Sancti Spiritus province, a member of our brigade asked if the staff participated in Cuba’s famous health brigades. Addressing the rows of white coats sitting behind us in the auditorium, the hospital’s director asked those who had been on international missions to stand. Not one person remained seated. At that moment, the director explained, staff from the hospital were working in 10 countries.

This is a commitment that stretches back through the revolution’s long history, but won global attention during the COVID-19 pandemic. On March 22nd 2020, Cuba’s ‘army of white coats’ landed in Lombardy, Italy. As the spread of COVID-19 forced international shutdown, 53 Cuban doctors flew to the epicentre of the pandemic to assist the overwhelmed Italian health service. This was the same brigade that travelled to Sierra Leone in West Africa to fight the Ebola virus in 2014. By 1 April 2020, nearly 600 Cuban medics had been dispatched to 14 countries to help deal with the impact of the pandemic.

In industry as in agriculture, wealth is shared by those who produce it. Standing on the roof of an electronics factory in Havana, I noticed what looked like one-quarter of a small football stadium on the grounds. “That’s where we hold our union meetings,” said our guide. Everyone at the factory was a member, managers were elected and could be removed every month. “They are my bosses,” said the factory’s director, gesturing to the union branch’s leadership. The union worked in the community too. Most of the workforce lived in the neighbouring barrio, where factory revenue funded development projects and maintained workers’ houses. While 3,000 solar panels made the workplace self-sufficient, the energy that remained was used to power the neighbourhood. The Cubans used the circular economy as a means of insulating themselves from the blockade. In contrast, although Scotland seeks to become a ‘circular economy’, soaring energy bills thrust workers into the jaws of loan sharks and landlords hover like vultures over rented properties.

Returning from the factory visit, a group of us taxied into Havana’s city centre for the evening. There were too many of us for one cab and not enough fuel for 2 cars. We would need to make two trips. As we drove, our driver explained that, while unconvinced by the government, he loved Cuba. “Biden is worse for us than Trump,” he said as we passed the steel fence that surrounded the closed American embassy. Biden, unlike his Democratic predecessor, has done nothing to ease the embargo. Obama on the other hand, as Gladys Hernandez explained, ‘had realised it was impossible to defeat Cuba with traditional methods.’ Life, said our taxi driver, was harder than ever.

Losing ourselves in the revolutionary tour, we had let the daily difficulties of life slip from our minds. For its refusal to bow to the forces of imperialism, Cuba has lost more than $130bn. Power cuts punctuated our days. We queued at supermarkets while ration cards were stamped. Food was expensive. Fuel was scarce. In April, President Diaz-Canel had been honest with the Cuban people. "We still don't have a clear idea of how we are going to get out of this situation," he said. Some we spoke to feared the dawn of a second special period. Young people’s aspirations were higher than in the 1990s. The creep of Americanisation and the weaponisation of social media threatened instability as with the protests of July 2021. Grounded once again, our conversation turned to the importance of material solidarity. Soon we would see exactly the difference it can make.

Nestled on a quiet street corner in the Playa district of Havana sits the Miramar Theatre. The building stands out as distinctly newer than those surrounding it. Opened in 2012, this £350,000 renovation was funded entirely by solidarity donations from the UK through the Cuba Solidarity Campaign and the Music Fund For Cuba. Miramar has no other spaces like it. The Theatre provides performance space to local art students but also a venue for the community to gather and hold meetings. The theatre is home to the ‘Sala De La Kirsty MacColl’. Devoted to a great friend of Cuban culture and the island’s people, the 450-seat auditorium serves as a testament to the strength of British-Cuban solidarity. Plaques honouring those who made contributions to the project adorn the theatre’s seats. “In memory of Kirsty MacColl and in tribute to El Commandante Fidel Castro,” read one.

We left Havana two days later. As we drove into Santa Clara on deserted roads, I was still thinking about the theatre. Sixty years ago, it was in this city that British-made Sea Fury fighter jets had strafed Che Guevara’s forces in the final days of the revolutionary war. I recalled Che’s words: “Make sure that we never trust imperialism, not even a little bit.” Eduardo Galeano echoed Che when he wrote that this paranoia forced the Cuban Revolution to “sleep with its eyes open.” His words speak to something it’s easy to forget, or ignore. The Cuban revolution is ongoing. Cuban socialism is a process always seeking to progress. The revolution’s opponents understand it as a bygone epoch survived by iconography alone. But the revolution is alive, constantly struggling for survival against those intent on banishing it to history. It makes mistakes and learns from them, assessing every new challenge through a framework rooted in theory but, importantly, practice.

We were surrounded by statues and literature, but only after leaving Cuba did I understand what prose can barely communicate. When past visitors said the revolution lives, they meant that Cuban socialism is moved forward by the everyday work of the people, not achieved overnight or imposed by decree. As international crises intensify, the task of international solidarity is to fight the blockade, help Cuba access what it needs to survive and, ultimately, keep the revolution alive. The Miramar theatre did this, but so too did the £100,000 worth of vital educational aid recently raised by the UK’s National Education Union and others.

In the closing days of our trip, we attended a street party organised by the local Committee For The Defence of Revolution (CDR) in Sancti Spiritus. The CDRs, formed in 1960 to defend the new government from counter-revolutionary violence, have evolved with the revolution. Today committees across the country provide vital community services. The entire neighbourhood poured onto the streets. We met young people who wanted to leave Cuba but said things would be different without the blockade. The US, they said, robbed ‘us of our future.’ Gathering everyone around, the CDR’s chair told us that in this neighbourhood people were not wealthy. The difference in Cuba, she said, “is we share what we have, not what we have left over.”

The next day we celebrated May Day. In the early morning sun, we marched through Sancti Spiritus. People partied to the tune of a samba band. Children played, weaving their way between banners and portraits of Che, Fidel and Jose Marti. The fuel crisis had scaled down Havana’s famous parade and heavy rain had cancelled the scheduled smaller celebrations. Workers’ Day was still marked but on May 5th. The Cuban revolution adapted, as it always did.

Back at the airport, we reflected on our experience. The US has stepped up its war on Cuba. The fuel shortage was crippling. Two centuries after the Monroe Doctrine was coined, Washington’s determination to control its ‘backyard’ remained unabated. People were angry but faith in the revolution’s capacity to offer dignity in times of crisis remained. “You are our messengers,” we were told when we first arrived. It is the task then of all those who reject Monroe’s politics of subjugation to build solidarity with the Cuban people so that the revolution may continue to defy imperialism’s gravitational pull.

You can support the Cuba Solidarity Campaign here.

Coll McCail is a Scottish activist, member of Unite the Union & Progressive International’s Secretariat.