The Internationale Forschungsstelle DDR (IF DDR) is a Berlin-based research centre dedicated to the re-examination of the history of the German Democratic Republic (DDR) and its enduring relevance for progressive movements today. Their new research platform “Friendship!” hosts contributions on the study of the socialist states’ internationalism and anti-imperialism during the 20th century. The following article is an extract from a longer analysis, which can be found on the IF DDR’s website.

Howard Catton of the International Council of Nurses recently warned of the devastating effects that the poaching of nurses is having on Ghana: "My sense is that the situation currently is out of control … We have intense recruitment taking place mainly driven by six or seven high-income countries but with recruitment from countries which are some of the weakest and most vulnerable which can ill-afford to lose their nurses."

For countries like Ghana, the brain drain of skilled medical personnel to the West only adds insult to the injuries inflicted by colonialism. As the imperialist powers withdrew from their colonies in the late 1950s and 1960s, they took their personnel with them, leaving massive gaps in the already-weak infrastructure of these countries. The newly liberated states were subsequently faced with the task of overcoming the deformities left behind by colonialism and rebuilding their societies. Health infrastructure was crucial in this regard: where basic medical care is lacking, there can be no social progress. As the former colonizers began turning to new “neocolonial” methods to preserve traditional dependencies, the national liberation movements found allies in the nascent socialist camp.

The emergence of a socialist world system after the Second World War meant that support for the national liberation movements could take on new dimensions. The people’s democracies of Eastern Europe and the People’s Republic of China now joined the Soviet Union in the assistance of the anti-colonialist struggle. Their solidarity was guided by the principle of delegation: through extensive education initiatives, young students from the former colonies acquired the skills and equipment they required for the construction of national infrastructure back home. The training of those who had hitherto been systematically denied educational opportunities thus had a fundamentally different character in the socialist states. The focus lay not primarily on the fulfilment of individual life plans or the realisation of a career; the objective was to bring an entire society out of the educational deprivation that had been imposed by the colonial powers.

An East German medical school dedicated to internationalism

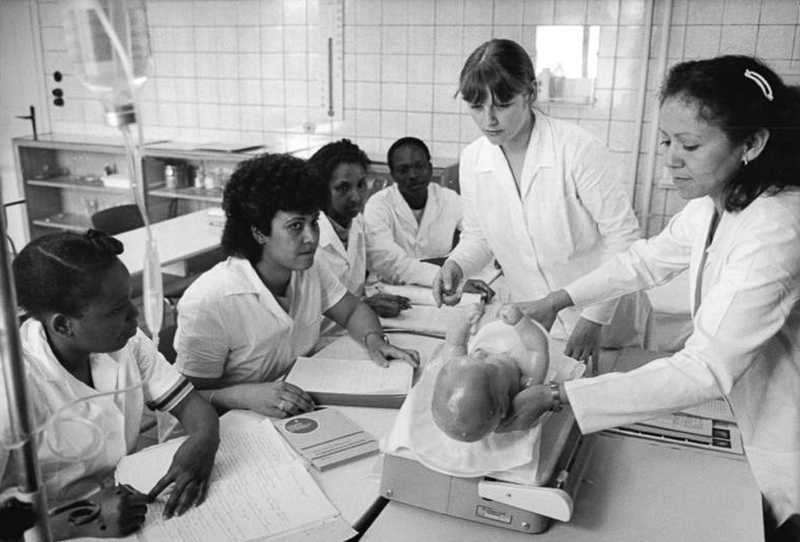

To better understand the character and methods of the socialist camp’s solidarity, we recently investigated how the principle of delegation was put into practice by the German Democratic Republic (GDR) in the medical field. Our research led us to the East German town of Quedlinburg where, from the 1960s onwards, the GDR operated a medical school explicitly for young students from the newly liberated states and national liberation movements.

Students came to Quedlinburg from Lebanon, Jordan, Syria, Mali, Tanzania, Laos, Egypt, the People’s Republic of Yemen, Madagascar, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Guinea-Bissau, Cape Verde, Palestine, Nicaragua, El Salvador, Laos, Cambodia, and many other countries. For the approximately 2,000 graduates of the school, the financing of their education was typically part of comprehensive trade or cultural agreements between the GDR and other states or political organisations. Many of these students came to Quedlinburg at a time when their movements were still fighting for independence. For some countries, the medical school in Quedlinburg trained their first native medical personnel.

Unlike in the West, where individual foreign students had to organize their own education, the GDR organized its training programmes through joint agreements and could thus tailor its curricula to the respective needs of the partner countries or movements. At the same time, foreign students in the GDR received sufficient scholarships to finance their living expenses and were directly integrated into the GDR’s health and social system, guaranteeing them free medical care during their studies. This contrasted with the system in capitalist West Germany where students were entitled neither to state assistance for students nor to the social programmes offered to FRG citizens. Thus, while education in the West was open to only the privileged classes of wealthier Global South countries, the socialist states made it possible for the “wretched of the earth” to take up an education. As one Palestinian graduate of the medical school in Quedlinburg told us: “Without the help [of the USSR and the GDR], I and thousands of others from countries all over the world would not have had access to an academic education. And this changed the outlook of the health services in the Third World.”

Indeed, the composition of the student bodies in the two German states vividly demonstrates this fact: In West Germany during the early 1980s, about 50 percent of all foreign students came from developing countries, of which just 6 per cent from Africa; during the same period in the East German workers’ and peasants’ state, non-Europeans made up more than two-thirds of the international student body, and almost a quarter of them were from Africa.

The medical school in Quedlinburg – or the “Medifa” as it was referred to by the former students and teachers that we interviewed – refined its training programmes over the years to adapt to the specific conditions in the students’ home countries. The students themselves were incorporated into this process and helped to develop their own curricula. Alongside nursing, midwifery, physician assistant training, and orthopaedic mechanics, the field of medical pedagogy became a core programme at the Medifa, for it enabled students to act as multipliers upon returning home; they could pass on the knowledge they had acquired in Quedlinburg and thus begin to erect self-sustaining health care systems.

Lived Solidarity

The Medifa’s core internationalist purpose was to train students for future responsibilities in their home countries; their stay in the GDR was limited by nature. Yet, diverse relationships grew out of everyday life at the school. The fact that these connections were often developed organically by those involved in and around the Medifa reflects a basic characteristic of the GDR, namely, that educational institutions were not isolated but closely linked to other areas of society.

The students from the Global South were not strangers to society, nor were their struggles. Many GDR citizens were well informed about their political movements and expressed their solidarity in private contacts as well as public manifestations, such as May Day demonstrations, where Medifa students marched as the first block in Quedlinburg. At the school itself, students also organised their own political events, cultural evenings and celebrations for their national holidays. A powerful example of these reciprocal contacts were the Patenbrigaden (“partner brigades”) between Medifa students and the workers in public enterprises around Quedlinburg. These brigades – which Medifa instructors had organised on their own initiative – gave students the opportunity to visit the socialist enterprises and experience in a very concrete way the different practices that the changes in ownership relations had brought about in East Germany. The students could participate in the production processes and learn about how the enterprises maintained their own health, childcare and sports facilities. East German workers, in turn, could attend German classes at the Medifa and discuss with students the developments in their home countries and movements.

The students were also able to go on holidays and excursions in the GDR, attend cultural events and get to know the everyday life of the population. It was common for students to be invited to parties or even family homes over the holidays. “We were mothers, we were sisters, we were friends, acquaintances, everything,” recalled Hilde, one of Medifa’s German instructors. Such personal relationships reflected and strengthened the ties between the countries and progressive organisations.

One building block in the worldwide anti-imperialist struggle

With the end of the GDR, the Medifa’s doors were also closed in 1991. The school and its international significance were erased from public memory thereafter. The students, teachers, and staff we met all associate positive and exciting life experiences with Medifa, yet its political significance and impact are given no recognition in the public sphere today.

The training of young students at the Medifa was not an act of selflessness or charity, as “development aid” is often portrayed to be today. The social and political progress of socialism depended on the advancement of the struggle against imperialism worldwide. Conversely, the liberation movements and former colonies were dependent on the assistance of the socialist states in the construction of independent structures and the emancipation from imperialist dependencies. The GDR’s approach – vividly illustrated by the Medifa – was thus based on genuine assistance that simultaneously functioned as an instrument in the common struggle against imperialism. As the Mozambican revolutionary Samora Machel described it: “International solidarity is not an act of charity: It is an act of unity between allies fighting on different terrains toward the same objective. The foremost of these objectives is to aid the development of humanity to the highest level possible.”

When researching the Medifa and the GDR’s solidarity work, we often tried to determine the concrete impact that such initiatives had on the newly independent states and liberation movements. Yet we came to realize that this question ultimately overlooks the historical significance of the socialist states’ internationalism. In the face of centuries of colonial maldevelopment, the impact of individual institutions like the Medifa was certainly limited. What is decisive, however, is that the direction of development was reversed: Not underdevelopment but reconstruction, not subjugation but sovereignty, not brain drain but education – these became the benchmarks of international relations. This reversal of the historical tendency marks the great achievement of practical solidarity, and it can still serve as a guide for an internationalist and anti-imperialist perspective today.