The celebrated 1889 dockers’ strike was nearly beaten when, out of the blue, money began to pour in from Australia to support the London strikers. Money came from the Wharf labourers of Brisbane, from almost every Australian trade union, even from Australian football clubs.

“The grip of brotherhood the world o’er”: the action exemplified the internationalism inherent to the trade union movement. Later, the (still active) International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF) built on this informal act of solidarity. There is something pleasing and right in the solidarity among those who make trade happen within nations and across borders. On this point, trade unionists have always been clear-sighted about the realities of the global economy. Edo Fimmen, the ITF General Secretary from 1919-1942, saw employers “practicing the division of labour on an international scale”, and urged workers in the west to recognize that the “struggle of workers in China, Japan and India was their own struggle”.

Today the International Trade Union Confederation is at the front line of the same struggle. Trade unionists share the goals of the Progressive International.

Critical to these goals is confronting the climate crisis, and the labour movement has developed and promoted the idea of “just transition”:

Workers must be involved in the design of their future through dialogue, consultation and collective bargaining. We want to see the transition happen on the ground, including through investment in new green jobs, skills, income protection and other necessary measures implemented with adequate funding for transforming local economies, and securing support for the poorest and most vulnerable nations.

Last year the Trades Union Congress (TUC) issued a statement that opens as follows: “the trade union movement recognizes that there is overwhelming scientific evidence of the need to decarbonise our economy”. These are big steps for a movement that has been justifiably fearful that unmanaged decarbonisation means unemployment: decarbonisation hits industries at the very foundation of the trade union movement, and green industries’ record on trade union rights is unproven. But the trade union movement recognizes that a decarbonized economy can be a part of a better economy, with better work and a better standard of life. Only outdated economics stands in the way.

Covid-19 and the economics of transition

Tragic and terrible on a human level, Covid-19 has immediately brought the more general economics of transition into sharp relief. Most obviously, the transition from lockdown should begin a just transition. But first we need better to understand the lockdown economy.

Unusually, governments have for the most part put the perceived interests of the economy in second place. Trade unions might contest whether the measures go far enough, and fear the hardship and stress suffered by sections of the public, but few doubt that the right thing has been done. Almost instantaneously a different economy has been operationalized, and this economy has been financed with ease.

The government has provided vast sums to support households and businesses; temporary hospitals have been constructed at pace, and in a few cases, housing found for the homeless. Society has witnessed action deemed unaffordable over the past decade at the same moment that tax revenues have collapsed with the partial shut-down of the economy. In the UK, a harsh light has been thrown on low pay and the economy’s warped valuations of workers – TUC analysis shows that four in ten “key workers” are paid less than £10 per hour. Financing has been made readily available through Bank of England money creation, including an announced additional £200 billion in purchases of government debt (“quantitative easing”) and so-called “ways and means” lending direct to government.

When it comes to the future, UK trade unions want another different economy, in particular one different to the economic regime we had before the crisis. The foundations of this different economy are a set of proposals to benefit working people. We call for the decarbonization of the economy and a UK industrial strategy, coordinated through tripartite dialogue between unions, employers and government as a “national council of reconstruction”. Similar structures at regional and local levels should be renewed as appropriate. We demand trade union rights in all workplaces, workers on boards, and wages and conditions set through collective bargaining at firm and industry level. We must tackle the structural inequalities faced by women, BAME (Black, Asian, and Minority ethnic) and disabled people, and all marginalized communities. Rather than empowered by the economy, disadvantaged groups have found themselves at the sharp end of policies that have entrenched and exacerbated discrimination and structural barriers. There must be decent public services and dignity in social security. We will work together for the same goals with workers across the world, and for a strategy to develop the economies of the most troubled parts of the world.

Any strengthened role for the public sector is not rival but complementary to the private sector. We need to dismiss the delusion that the public sector is paid for by the private sector. Taxes may fund public sector wages, but these salaries are spent in the private sector; in 2017 alone, “procurement” – public sector direct purchases from the private sector – amounted to £160 billion.

Austerity politics, war and peace

While George Osborne and others are already ramping up for post-coronavirus austerity politics, the real enemy is not austerity but the idea that we must restore the pre-coronavirus economy. Instead we must reject the idea that there is only one possible economy, which constrains everything we do. We insist that work defines the economy, not the other way around. The question of how we pay for the lockdown ceases to have any relevance when we choose to have a different economy.

Many have sensed a parallel between the lockdown economy and war, but the most important parallel is with the transition to peace. Only after the Second World War were pledges to workers and soldiers honoured, because after the post-war Labour Government delivered a different economy – a vastly better economy.

After the First World War, government spending was cut in two waves (the second infamously known as the Geddes Axe, after the minister responsible); interest rates were set high to reward creditors; and the sterling exchange rate was fixed high to protect and encourage overseas asset holders.The result was the most disastrous decade for the British and global economy in modern history.

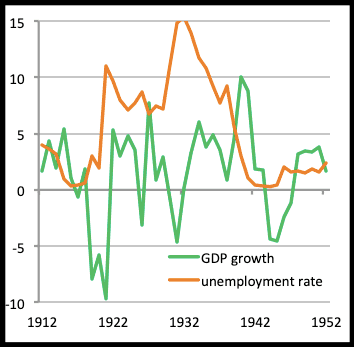

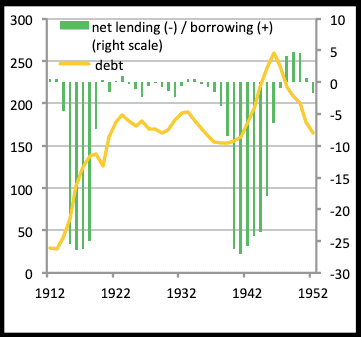

To assess relative performance, Figure 1 shows UK GDP growth and unemployment rates and Figure 2 shows government deficit and debt ratios (data from the Bank of England).After the First World War the deficit as a share of GDP was brought into balance – just – but the public debt ratio didn’t budge. Attacks on wages led to a grave breakdown in industrial relations, culminating in the 1926 general strike. Ultimately, the economy was upended with the global Great Depression of the 1930s.

Figure 1: GDP & Unemployment

Figure 2: Government Finances (% GDP)

The confidence for such a bold programme was facilitated by wider changes in thinking, organization and infrastructure. Trade unions and leading Labour politicians played a central role in the conduct of the Second World War, in particular the arrangements for production and the deployment of labour. Trade unions were instrumental in devising the policies and economic agenda that the Labour Party took to the electorate in 1945. In office, the Labour Government continued to work closely with trade unions, not least securing a non-inflationary wages pledge that endured until the Korean War. No less importantly, Keynes’s work reflected his understanding that the economy needed to change. The Great Depression exemplified the failure of the existing system, and his monetary theory explained how to construct a different and better economy.He understood the Depression as a crisis of financial excess rather than economic excess; the scale of the crisis had no bearing on the future potential of the economy if properly run.From the end of the gold standard in the 1930s, the financial infrastructure of the world was changed to permit that proper running, culminating in Keynes’s plan for a global clearing union – a plan diminished but not entirely undone by the Bretton Woods agreement.

Transitions in the present

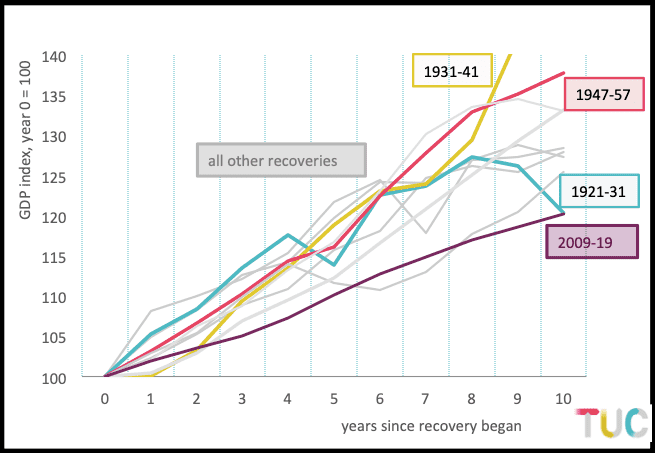

Austerity is based on the same doctrine that was deployed after the First World War. As the TUC has pointed out, GDP statistics from the trough of the recovery to the present (2009-2019) show the worst recovery for two centuries. It is unsurprising but very striking that the only “recovery” in the past century that is in the same ballpark is the decade of after the First World War (Figure 3). Conversely, the recovery from the Second World War is at the top of the pack. (Though the expansion into the Second World War moves the 1931-41 recovery very clearly into the front.)

Figure 3: GDP recoveries over the past century

The past decade only reconfirms the results of assuming change is not possible. The economic response to Covid-19 reminds us that change is possible. We must understand and emphasise that doing right for society and the climate will be right for the economy.

The transition from the lockdown will be challenging for many workers. But sacrifice and hardship can only be honoured on the understanding that a new economy will be a better economy. As under Attlee, this new economy will, over time, pay for any borrowing incurred at present and in the transition. More Bank of England support may be necessary, especially in the short-term; unlike under austerity policies, these interventions will support success rather than failure. We should aim for an economy that delivers decarbonisation, with decent social care and public services. We can and must reposition the economy to serve society, not the other way round.

Photo: Terence Faircloth