International, because environmental policy cannot stop at national borders or it risks the “hot potato” effect of merely relocating pollution, extraction, devastation. And given vast and longstanding global inequalities, there remains the oft-promised but never implemented principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities”, or put otherwise, the need for the North to pay its ecological debts. As for intersectional, any efforts to deal with climate change and biodiversity loss must be feminist, anti-racist, and decolonial.

Why? First, it is well-known that environmental policy plays out inequitably, so questions of social and environmental justice are obviously central concerns of any Green New Deal. Second (and closely related), as Naomi Klein made clear in her Edward Said lecture a few years back, sacrificial bodies and places also drive environmental change. Sacrificial bodies are a critical fuel for carbon capitalism.

Global environmental justice activists have been familiar with this dynamic for decades. Bodies deemed “lesser” shoulder the ill-effects of climate change and biodiversity loss all along the commodity chain: from production to waste; in the extraction of fossil fuels, and in the impacts of burning them. The sacrifices demanded by extraction are clear, for example, in Nigeria, where people continue to live in toxic dumps of oil and amid poisonous gas flares. On the other end of the chain, impacts from ecological change are also gendered, racialized and always geographical. The ability to cope with or move away from uninhabitable heat and other climate change effects—drought, floods, storms, rising oceans—is of course not the same for everyone; it’s shaped by race, class, gender, colonial histories.

Where we live in Canada, extraction is most negatively experienced by Indigenous women; risks of sexual violence for Indigenous women and girls rise steeply when what are known colloquially as “man camps”—industrial camps housing workers in extractive industries—are built on Indigenous territories. Indigenous women’s reproductive health is also compromised by extraction, while they are the least likely to benefit from employment in these sectors, known for persistent racism and sexism. Extraction in western Canada is also driving spiraling wildlife loss among species like caribou, a problem not only from an ecological perspective, in terms of declining ecological abundance and diversity, but a matter of environmental justice and survival for communities like the West Moberly First Nations and many other Indigenous nations.

To sum up: gendered, racialized and colonial hierarchies are drivers of ecological crisis and render some people and species more sacrificial than others. This is now a bit of a mantra in green politics, thankfully—a remarkable shift in mainstream environmentalism. We’ve seen these views articulated in Canadian versions of the GND, going back to the 2015 Leap Manifesto, which explicitly identified gender and racial inequalities as central to any climate politics, including prioritizing and re-investment in care work. (From our pandemic-sequestered homes we think, wouldn’t that have been great; imagine where we would be at the tail end of 5 years of concerted public investment in care work!).

Most explicitly and awesomely, last year a group of organizations released principles for a “feminist Green New Deal”, which included among them need for a gender analysis of any GND policies, among many others. What can we add to this remarkable product of organizing and solidarity? Not much. But we would like to draw out a key implication for green or ecological movements, and for a global Green New Deal.

If we agree that sacrificial bodies are key inputs into the processes driving ecological emaciation and climate apocalypse (and we do), then movements organizing against hierarchical difference-making are also ecological. Antiracist movements, socialist-feminist movements, reproductive justice and decolonial movements are ecological, even if they do not list climate change or deforestation in their platforms. Any movement or action that aims to make some persons or groups less sacrificial, to change norms of white supremacy, and to disrupt gendered, racialized and classed hierarchies is crucial work toward a GND, even if there is nary a windmill or solar panel in sight. These movements, like any others, are of course insufficient on their own, but still necessary and, also, ecological or “green”.

This perspective aligns with a key principle of the feminist Green New Deal, calling on us to confront institutional patriarchy and racism in our communities, movements and policy-making spaces. An international and intersectional GND will focus not only on developing and advocating for progressive financial mechanisms, including increased (and ideally international) taxes to underwrite massive public investment in renewables, but it will also work on recognizing and dismantling hierarchical difference. This work, dare we say the work of identity politics (a Black feminist-coined, but now-loaded term), is too often dismissed as small potatoes, or worse, as divisive. But any successful global Green New Deal must embrace a multi-scalar notion of the political, to include both the macro and the micro, from Indigenous blockades to the everyday work of building less hierarchical relationships, a point made eloquently by Indigenous feminist Sarah Hunt.

In fact, far from being small potatoes or divisive, everyday political struggles against hierarchical difference multiply the openings for green politics. Many people want to resist climate change but struggle to find levers of influence on, or paths of action into, what seems like an intractable planetary problem. Students, emboldened by the school strikes regularly rippling around the world, wonder what they can do in between the street protests. If we agree that racialized and gendered inequalities contribute to ongoing ecological injustices, then there are green political handholds close to home, addressing those very same inequities in all the places we inhabit: homes, streets, workplaces, universities, and on school boards and in board rooms. The terrain of green politics and political possibility widens, and, we think, must keep getting wider.

Covid-19 draws our eyes especially to potent places where ecological politics and feminist politics enmesh: in struggles to advance reproductive justice, another principle of the feminist GND. Reproductive justice is a theory and movement developed by women of colour in the 1990s to identify and challenge ways that race, class and gender inequalities constrain reproductive freedom. As legal scholar Dorothy Roberts puts it, the movement includes but goes beyond access to abortion, demanding “the right to have children and to raise them with dignity in safe, healthy, and supportive environments”. This includes access to safe living spaces, domestic violence prevention and survivor support, and living wages for families. Reproductive justice is under the spotlight right now, as Covid-19 is not only impeding women’s access to abortion but is also exposing the extraordinary degree to which undervalued but absolutely essential reproductive work is still done by women and especially women of colour. These issues are rarely linked to green politics, but we see important, even necessary, connections.

Access to abortion, never fully achieved in most parts of the world, has been a core feminist rallying cry for decades (most recently in the successful Irish referendum to repeal the country’s abortion ban, and in the green wave across Latin America). Even when formally recognized, the right to access abortions is always somewhat precarious, constantly under threat. In Spring 2019, a rash of new bills passed in several US states constraining or even barring access to abortion. Laura Penny, writing in the New Republic, remarked that “these laws are not about whether a fetus is a person. They are about enshrining maximalist control over the sexual autonomy of women as a foundational principle of conservative rule. They are about owning women. They are about women as things”. The connections to Trump’s campaign and administration, which frequently elevate and defend traditional gender hierarchies, are clear. Jamelle Bouie argues that we should understand the “new wave of abortion restrictions — as direct attacks on the social and economic autonomy of people who can become pregnant, restrictions designed to strengthen strict hierarchies of gender”.

These contemporary attacks on women’s bodily autonomy are often understood as separate from the economy and environment—more a matter of cultural politics, social conservativism, religion. Worse, when access to abortion, or to birth control more broadly, are discussed in the environmental sphere, it is usually within a “nasty, resilient strain of thinking within the left that views birth control as a means of addressing social and environmental problems like poverty and ‘overpopulation’”. The seemingly never-ending, usually racist, blame-game of population growth further hampers women’s reproductive freedom.

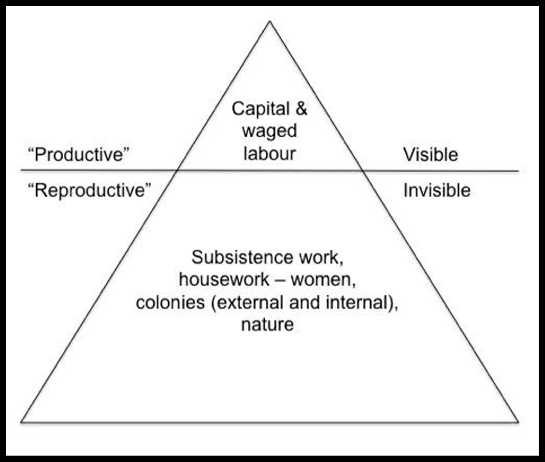

In contrast to the overpopulation scare-mongers, feminists like Leanne Simpson, Donna Haraway, Val Plumwood, Maria Mies, and Silvia Federici draw entirely different connections between environmental catastrophe and reproduction. They link assaults on nature and women’s autonomy to the rise and “success” of colonialism and capitalism. Constraints on women’s autonomy are tied to the construction of the nonhuman world as stock of cheap resources to be extracted, and as a free sink for waste (like carbon dioxide or toxic chemicals). Social and ecological reproduction—broadly, how living beings and the communities of which they are a part make and remake their lives—is devalued, treated as inferior or lesser than production and accumulation, and subject to strict and coercive control. This means patriarchy is an ecological regime. Women and nature are consigned to a marginalized, devalued reproductive realm. Maria Mies, a pioneering feminist political economist, has illustrated this perfectly in her not-as-famous-as-it-should-be iceberg metaphor. Access to abortion, as a condition of possibility for women’s autonomy, is a refusal of patriarchal rule—rule that is bent on keeping women and nature controlled, devalued, and cheap.

Reproductive justice, then, is about valuing and guaranteeing autonomy in the reproductive realm, a realm which includes the creative energies and sophisticated capacities of nature. In Roberts’ words, “true reproductive freedom requires a living wage, universal health care, and the abolition of prisons”. It requires non-toxic places to live. Bodily autonomy and ecological justice are intertwined.

This is a key point in the organizing work of Indigenous feminists known as the “tiny house warriors” fighting ongoing colonial extraction (projects supported by various levels of government in Canada) on Indigenous territory. And it is another crucial principle of the Feminist Green New Deal: “Our fights for climate justice and for bodily autonomy are linked. For example, toxic chemicals that pollute our water, air and land jeopardize our health, including reproductive health, often with a disproportionate impact on Black, Indigenous and Latinx women due to systemic and institutional injustice… We affirm that the true causes of our global climate crisis lie in industrial policy and that a sustainable future requires bodily autonomy and sexual and reproductive rights in all circumstances”.

Covid-19 simultaneously heightens and reveals the inequalities and injustices in our societies, including those determining women’s autonomy. The virus shines a light on the reproductive work that so many women are doing—work both paid (albeit poorly) and unpaid. Newly-recognized as “essential,” jobs in elder care, social work, and retail are usually minimum wage or close, staffed by women, immigrants and racialized people. A new UN report on “How COVID-19 is changing the world” notes that around the world, women comprise 70 percent of the health care workforce and do as much as three times the unpaid care work as men. In the US, “of the 5.8 million people working health care jobs that pay less than $30,000 a year, half are nonwhite and 83 percent are women,” and “nonwhite women are more likely to be doing essential jobs than anyone else”. Many of these jobs have always come with high risk of injury, and now, of course, the risks have jumped considerably. Much of women’s unpaid reproductive work is done in homes, where rates of domestic violence have spiked. Meanwhile essential work outside the home exposes workers to COVID-19. Accordingly, the uneven exposure of racialized people to the virus manifests in their starkly disproportionate death rates, calling to mind longer histories through which communities of colour have been denied the ability to bear children and raise them in safe environments.

Bodily autonomy is also under threat. Women’s work is now viewed as essential, but abortions have in some jurisdictions been classified a“non-essential” medical service. As a result of the virus, access to abortion is impeded everywhere it exists, however precariously.There are“delays and disruptions in every step of the supply chain that brings critical safe abortion medication and contraceptives from Asia to East Africa—halting factory production, delaying air and sea shipments, complicating customs approvals, and restricting in-country transport from seaports and airports to hospitals, pharmacies, and health care clinics”. Given these disruptions, experts predict increases in unintended pregnancies and unsafe abortions, exacerbating already unacceptable rates of death among women from lack of access to safe abortion and reproductive health care. Lockdowns and physical distancing also limit access to abortion, and the burden on health systems is “likely to substantially reduce abortion access”. Meanwhile, USAID has requested that the UN pandemic response plan remove any mention of women’s reproductive health, as reported by CNN.

What could a feminist, global Green New Deal response to Covid-19 look like? The good thing is that there is growing recognition of undervalued but essential reproductive labour, of all the care work done outside and inside the home, work often shouldered by women. The bad news is that these very same women face increased precarity and constraints on their reproductive autonomy. So while green advocates rightly focus on this once-in-a-lifetime chance to see massive investment in a just transition, following the principles of the feminist Green New Deal, the condition of reproductive justice on the other side of the pandemic will have deep implications for the possibility of ecological justice. Reproductive justice is environmental politics.