A VivaSUS Forum interview with Gabriel Brito

A national benchmark in the privatization of public services, São Paulo has relied for years on the nonprofit healthcare operator (OSS, or "Organizações Sociais de Saúde" in Portuguese) model as a method for managing the SUS (Brazil's public health system). Created in 1998 during the Cardoso administration, this legal-administrative structure requires entities to declare themselves nonprofits—but after more than 15 years of operation, it's clear that such nonprofit status is highly questionable.

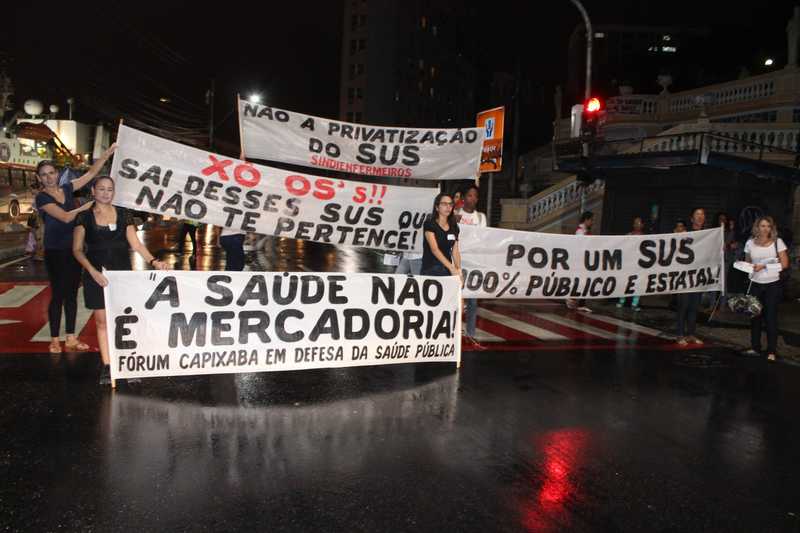

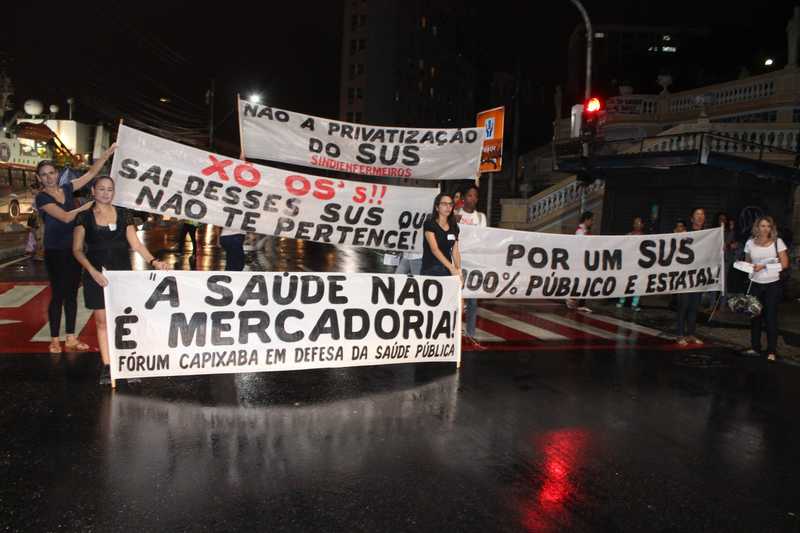

Those who are critical of the nonprofit operators are those who actually constitute the SUS, from system workers to researchers and activists. It is against this discouraging state of affairs that the VivaSUS Forum was created in São Paulo—perhaps the most recent social movement in defense of the health system, which for decades has faced the inevitable contradictions generated by the supremacy of market culture. Formed by healthcare professionals and system users, it was established in 2022 in response to the Portaria das Metas (Goals Ordinance)—a milestone in this undermining that imposes industrial rhythms on healthcare.

"Working in the SUS is demoralizing, sterile, fragmented, isolated, and contentious. There is no possibility, no chance to be creative, to think of care that makes sense for the public. We talk about reclaiming the SUS, but throughout our reflections we concluded that it was never really ours," its representatives said in a hard-hitting collective interview with Outra Saúde.

The very fact that they avoided revealing their identities demonstrates the toxicity of labor relations and of management based on the OSS model, which has become an obscure channel for public funds.

"It's a way to circumvent the law, because it's the same public money used to hire people. The nonprofit operators enter this vacuum and begin to operate as companies, even if they declare themselves to be nonprofits. More than 80% of São Paulo's health budget is in the hands of the nonprofit operators; it's a lot of money, billions of reais handed over to private, commercial management, because that's what they really are," the collective criticizes.

It must be understood here that the rules of fiscal austerity and control of "spending" are arbitrary techniques cloaked in ideology, which consider this same money to be free of legal limitations when managed by private actors. In the end, an expensive and inefficient system is created, contrary to the promises of the ideologues of corporate managerialism applied to the State.

In this conversation, VivaSUS details how the nonprofit healthcare operators have weakened public oversight, transforming technical positions into political appointments and undermining the State's ability to manage its own health policy. They also denounce the farce of private efficiency, which delivers billions of reais in public funds into the hands of companies that dismiss people without just cause, engage in labor fraud, and impose goals incompatible with comprehensive care.

"We notice the State's decreasing capacity to manage public health policies and the increasing power of these companies, the managers of these companies, and their owners—because that is what they are: companies with owners," warns VivaSUS.

In addition, the workers explain that the São Paulo experience is increasingly replicated nationwide. This model, based on false parameters for guaranteeing the right to healthcare, represents an entire market-driven logic adopted by various other population centers. And worse, by the federal government itself.

"Much of what was lost and revoked by the Temer and Bolsonaro administrations has not been recovered. When you have, for example, the maintenance of primary healthcare based on supposed goals, we see a government held hostage by market logic, which will have a real impact on our activity as workers.

For the VivaSUS Forum, the 35th anniversary in 2025 of Brazil's unique health system is more a call to fight to ensure its future than a celebration per se. Here is the full interview.

What is the Viva SUS Forum, why was it formed, and what is its reach?

It's an autonomous, horizontal, and nonpartisan social movement, driven by workers and by people who use the SUS here in São Paulo. It began as a response to the publication of the Portaria das Metas back in 2022, which was the final straw of the worsening and distortion of work in the SUS, following an increasingly business-like production logic under the management of nonprofit healthcare operators.

The way SUS has been set up in São Paulo, we, the workers, find ourselves forced to take care of numbers, no longer of processes, people, or territory. Working in the SUS is demoralizing, sterile, fragmented, isolated, and contentious. There is no possibility, no chance to be creative, to think of care that makes sense for the public. That's why we came together around the idea of raising awareness, provoking, and organizing workers and people who use the SUS.

We talk about reclaiming the SUS, but throughout our reflections we concluded that it was never really ours. Maybe the idea is actually to raise our awareness, to equip ourselves, to collectivize, to organize in order to transform the system and to propose a model of healthcare access that makes sense for society.

Being in São Paulo, do you see the state and the capital city as laboratories for what might be privatization within the system? What historical assessment do you make of the nonprofit healthcare operators?

The nonprofit healthcare operators emerged as a way for administrators to speed up and simplify hiring. If we think about the beginning of the system, when there were far fewer services and people hired, the administrations—especially PT and PSDB—used this resource to make the system grow, in terms of its reach. But without addressing the main problems, such as budget policy, the fiscal responsibility law that limits hiring, public spending on personnel, health, education...

Moving to the private sector is a way to circumvent the law, because it is the same public money used to hire people. The nonprofit operators enter this vacuum and begin to operate as companies, even though they declare themselves to be nonprofits. More than 80% of São Paulo's health budget is in the hands of the nonprofit operators; it's a lot of money, billions of reais handed over to private, commercial management, because that's what they really are.

And here we get into the treatment of employees. They can dismiss people because this is under the CLT (Brazil's consolidated labor law) system, so they don't need justification, even in relation to people who provide public healthcare services. We have several cases of dismissals in which, when they go to labor court, they claim not to be private companies.

The SUS is widely recognized as a model for public policy. Despite everything, the SUS delivers a lot. We managed to stop some privatization efforts, but within the system they managed to build power and already have most of the budget. And if they have a budget, they also control the management of the system. We see the nonprofit operators coming up with models, deciding which information system will be used to develop medical records, management of the production network...

And there appears to be no criticism anymore of this type of management model, which claims to be more efficient, but in practice is nowhere near meeting the needs of the SUS-using public.

It's important for us to look forward. As workers and users, we need to understand the limits of this system in order to dream and fight for alternatives. There are a lot of people, including on the left in São Paulo, who think this isn't possible, because the nonprofit operators are too large and somehow ensure that the continued operation of the system. But we need other ways to hire, to manage the SUS, and to manage work.

After more than a decade, more than 90% of the workers in the city of São Paulo are hired by the nonprofit operators. And we notice the State's decreasing capacity to manage public health policies and the increasing power of these companies, the managers of these companies, and their owners—because that is what they are: companies with owners. We have less and less voice, we are being undermined, and this affects the idea of societal control of the SUS, both by workers and by the public.

Another aspect is that with the end of hiring statutory civil servants, more and more of the hierarchical levels of the São Paulo city government are being filled by appointed positions. Positions that 10 years ago were managed by career civil servants committed to the implementation of public policies, and with an understanding of the SUS's theoretical and practical framework, are now being occupied, down to the lowest levels of administration, by local advisors in each neighborhood or health subdistrict. Advisory services for mental health, women's health... Everything is being transformed into appointed positions.

What does that mean?

With this erosion of the power held by municipal employees who have passed public service exams, power ends up being transferred to the owners of the nonprofit healthcare operators who, in collusion with the elected mayors, appoint people based on political connections, without a genuine commitment to the SUS.

In addition, with the fragmentation of the labor relationship and several different nonprofit health operators involved, workers no longer see themselves as an integral part of the SUS itself, but often rather as members of the company managing the SUS in that region.

This undermines fundamental aspects of the SUS from within, such as the building carried out by its own workers, through the implementation of a national health policy that opposes the commercial logic established by this type of appointment and by the inappropriate relationship between public authorities, appointed positions, and business owners.

When applied to the implementation of work goals, this harms workers, the quality of care, and weakens the population. Because with this concentration of power in the hands of political appointees and in the hands of companies, the mechanisms of public oversight are weakened. Be it health conferences or local or municipal management councils, everything is eroded.

Nowadays, we live in a situation in which the mechanisms once recognized as decision-making no longer have real power. The appointed political positions are reaching lower and lower levels, because there are no more statutory employees (who have been retiring) to pursue a career in the public sector, and so the owners of the nonprofit healthcare operators locally decide what they want.

Can we say that this logic remains untouched by the federal government, elected with the decisive support of the social movements that are fighting for improvements in the SUS and its own workers?

The logic implemented in São Paulo though the nonprofit healthcare operators is also upheld in the federal government, that is, the neoliberal logic of health as a commodity, for example, the idea of popular health plans costing 100 reais, developed inside a government agency (ANS). This is directly opposed to the SUS, which is universal and free. But it would align very well with what is being implemented in the city of São Paulo.

It's true that we've had six years of blackout, but there is a lack of dialogue and of national indicators for monitoring both health investment and outcomes. Something similar to what happens in São Paulo, where the parameters of the procedures are not related to the results.

Dialogue has also deteriorated at state and municipal levels, including with institutions such as COSEMS and CONASEMS, as well as universities. Everyone only looks out for themselves, and we don't have a tripartite SUS, as it should be not only in financing, but also in the evaluation of results.

Therefore, what happened with the legacy of the Michel Temer and Jair Bolsonaro governments, which clearly accumulated administrative measures to undermine and defund the SUS?

Like all social movements, VivaSUS analyzes this as a whole, and so you can't just talk about the current government without considering the Temer and Bolsonaro governments. The Previne Brasil [Prevent Brazil] program, which introduced a managerialist model that required specific activities in order to receive funding, was a positive change in financing compared to the funding model under the Temer administration. This was a very important change, because how is care measured in the psychosocial services network, for example?

But we had changes in the approach to primary care, the model for which had already been discussed in the history of healthcare reform, and this model was reintroduced within the ultra-neoliberal system advanced by the Bolsonaro administration. In practice, there are a number of issues that hinder and obstruct good work.

In São Paulo, the matter of goals is a clear example and embodiment of all this. And then when we have a federal government that calls itself leftist, we think things will change, even more so after the reorganization of the National Immunization Program after the trauma of COVID-19 and the anti-vaccine discourse.

But much of what was lost and revoked by the Temer and Bolsonaro administrations has not been recovered. When you have, for example, the maintenance of Primary Health Care based on supposed goals, we see a government held hostage by market logic, which will have a real impact on our activity as workers, as seen in capital cities like São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Fortaleza, Florianópolis...

In all these cities, we see a market-oriented view of healthcare. It's no wonder that the profits of these private companies, which are the big healthcare lobbying organizations, just keep increasing and just keep growing. And isn't this discussed, isn't it noticed? On the contrary, we have an administration discussing a project to expand private health insurance plans, an idea from the Temer administration and its minister, Ricardo Barros.

Therefore, we must indeed criticize the federal government and demand greater attention to the proposals of social movements and actors in the sector—who support it. It seems that everything only exists to satisfy the financial market. At what cost? You can't run the SUS with such explicitly market-driven logic.

It's always a quick market-driven attempt to also respond to social issues. Even when it tries to include social movements in the discussion, we see a government completely disconnected from the workers' agenda and aligned with the logic of the financial market, which closes its doors to us.

In general terms, how do you view the organization of the SUS in light of its fundamental principles, at a time when governments, institutions, and social movements are celebrating its 35th anniversary?

The celebration is important, but we aren't going to uphold the fundamental principles of the SUS without thinking about how work processes are actually organized. Not only from the workers' point of view, but also with regard to public oversight and participation. São Paulo is an example of how market-driven logic implemented through nonprofit operators, combined with opportunistic political interests, is undermining these principles, both in the organization of the workers themselves and with regard to public oversight.

These days, public policies aren't decided directly by the public and by the workers. It's a logic that's being implemented from within this system today and destroying the organizational capacity of a Unified Health System, as stated in our Constitution. This is a subversion, something that is destroying the SUS and ceasing implementation of its principles.

On a broader scope, how do you assess the federal government's performance in the so-called reorganization of the SUS after years of dismantling by Temer and Bolsonaro, marked above all by the health disaster caused by the management of the pandemic?

When it comes to the guiding principles of the SUS, the question remains whether we can keep universality when someone has a stomachache or flu symptoms and goes to their UBS (local health clinic) and ends up leaving in tears after waiting 6 hours, 8 hours, only able to see the doctor if someone else doesn't show up, because there just aren't any appointments available. That person doesn't get care and feels extremely humiliated, from both a worker's and a user's perspective.

It's not enough, it's not happening, this can't be called a SUS according to public policy. How is it possible to ensure equity if we see serious domestic cases and can't get care because the services responsible for rehabilitation, for example, have so few professionals and such a long waiting list that they provide care for only 2 years and then discharge patients, saying they've reached the treatment limit, even though they haven't? This is because they have to turn patients away to give others a chance to be seen. Because there's no way to serve all of them at the same time, there's no way to guarantee that all of them have access to healthcare. You decide at the end of the day who will have access to healthcare today and who won't, who will have to return home without treatment and continue living only half a life. A life without access to functionality, without access to quality of life, without access to social participation, without access to conditions of sociability.

And what kind of comprehensive care can we achieve if we see them—even with a multidisciplinary team—for 15 minutes? One doctor alone has long been unable to see a person as a whole. And even less so for a multidisciplinary team. Because appointments don't have the most precious resource of all, which is the time to understand what that person's life is like beyond the symptoms, their daily routine, their social relationships, what kind of food they have access to... So many issues that are much more complex than just taking complaints and prescribing something. "Oh, do you have a headache? Here, take your medicine.” "Are you experiencing anxiety? Have some auricular acupuncture." This is not comprehensiveness.

Returning to the development of the social movement, the labor issue is central to the VivaSUS Forum. What can you tell us about the meeting held on the 17th in São Paulo under the theme of "Reclaiming SUS"? How would you describe the current daily working conditions in the SUS, and what are you proposing?

Our initiative was also a response to the false First Meeting of the Psychosocial Care Network (RAPS) that the Municipal Health Department set up last year, in which workers were basically silenced by the panel. There was a suppression of criticism, a deliberate attack by one of the guests on the panel who suggested that SUS workers were acting like oppressors for not wanting to dialogue with the nonprofit operators and their technical supervisors, when the reality of oppression is exactly the opposite. The meeting proposed by Viva SUS was another of the movement's weekly activities—which take place in the community, in education, and alongside other social movements—a time for a lot of sharing that was also a major event.

It was very beautiful and reinforced some issues. Nobody can stand working for a company that's pretending to be the SUS anymore. Many horrible situations of harassment and institutional violence within the SUS were raised. The number of politically driven firings is increasingly alarming. Workers are fired for defending the SUS. That was a meeting that aimed to raise awareness and restore the strength of workers to fight for the healthcare we stand for.

We're looking for more strategic, organized, and creative action. And we're very excited about what we can do collectively.

There's a public demonstration scheduled for the 30th in downtown São Paulo, called Destrava SUAS [Unlock SUAS]. What are the central criticisms of the Forum regarding this dimension of the health and social services system?

We always think of the worker as the central focus, because every person should have a decent job in order to make a living. But when we think about the health and social services system, we see a great paradox: if basic policies of basic sanitation, housing, food, culture, and leisure were universalized, perhaps the health system as we understand it today wouldn't even exist, even with the best intentions and structures.

But since it does exist, it's hard to see therapeutic communities strongly supported by the federal government and a weakening of the Unified Social Services System (SUAS). Why not strengthen the SUAS, while we consider access by people who are, at times, in precarious and vulnerable situations, and who would also benefit from that system? Because we think of a model that locks people up, that oppresses, assaults, and violates people as a form of "care." How do we justify this in a government that claims to be a welfare state? We must consider these contradictions, be able to think about them, and think that every struggle is valid, as long as we consider such forms necessary.

Gabriel Brito is a journalist for the website Outra Saúde.