Each winter, Delhi disappears into its own breath. The sun dims behind a thick grey wall; the horizon blurs; the air tastes of burnt crops and diesel. People joke about “smog season”, as if a slow public asphyxiation were as natural as the monsoon. Those who can leave, do. The rest of Delhi — its millions of migrant workers, cleaners, builders, drivers, those who keep the city alive — suffocate in slow defeat.

Over the decades, India has perfected a way of surviving catastrophe: the rich simply opt out. When healthcare fails, the rich build their own hospitals. When the water turns brown, we install filters at home and lay private pipelines. With every blistering summer, Delhi rebuilds itself as an archipelago of air-conditioned fortresses, each a small insurance policy against the failure of the collective. Health is purchased, education is corporatised, water comes in bottles, safety comes with private guards. The capital rebuilds itself as a mosaic of escapes — malls humming above drains of stagnant filth, gated colonies with apartheid-era segregated elevators glittering beside the slums that service them.

We live by subtraction — each family, each fortune, carving out a liveable island from a collapsing sea. A logic of separation, of purity and pollution that descends from the oldest grammar of the subcontinent, where the old taboo of caste eternally finds new technology.

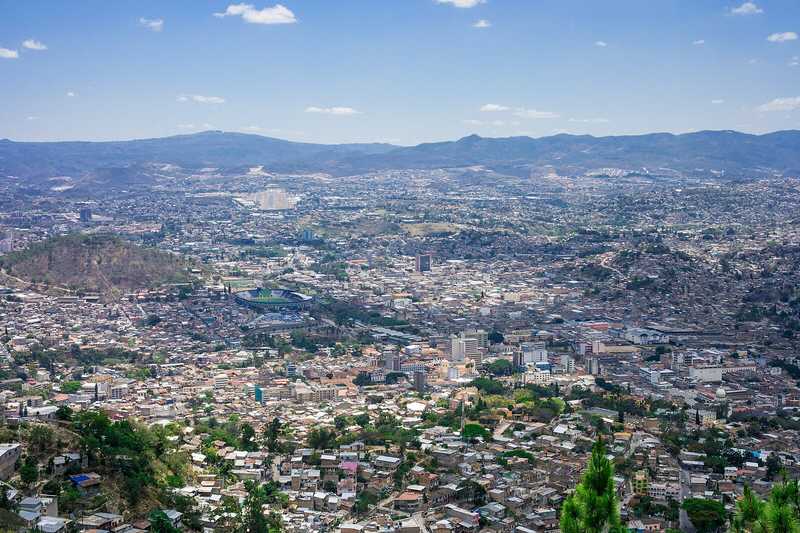

But the air refuses to obey. It seeps through glass towers, over compound walls, into every lung. The city’s air is now 15 times dirtier than the World Health Organisation’s safety limit, enough to erase eight years from an average life. In 2023, polluted air was linked to nearly one in eight deaths in the capital — not in dramatic bursts but in the quiet attrition of strokes, heart disease, lung failure and low-weight births. Air is the last public good that cannot be bought, bottled or enclosed — and it is poisoning every child playing in an open field, poor and rich alike. Still, why does nothing change?

The government has responded with ritual theatre. The Union government blames Punjab’s farmers; the Delhi government, its predecessor. An investigation this month revealed that water sprinklers were being driven around the city, not to ease the smog, but to be sprayed on the sensors at pollution-monitoring stations to lower the Air Quality Index (AQI) readings — cleansing the data rather than the air.

Delhi’s chief minister claimed to stand on the banks of the infamous Yamuna river for Chhath Puja, dipping her feet into what looked like a serene pond. Photographs later showed it was a fake ghat — a man-made enclosure filled with filtered water, cordoned off from the polluted river that the Delhi Pollution Control Committee had declared “unfit even for bathing”.

This choreography is not new. During the summer of 2021, when the Ganga became a grave, the New York Times suggested that India’s total pandemic toll might exceed 1.6 million deaths, 14 times the official count. But the government steadfastly refused to publish detailed data, and when researchers and journalists began analysing the National Health Management Information System to study excess mortality, the dataset was quietly pulled offline, data journalist Rukmini S. has pointed out. Twitter (now X) was ordered to take down posts that criticised the government’s handling of the crisis — among them photographs of cremations, pleas for hospital beds, and reports of oxygen shortages. India could not breathe, and now it could not speak.

The complete absence of governance — and of any expectation of accountability — is what defines Delhi’s response to pollution today. The city grows upward, outward, endlessly, but never together. Policy is replaced by blame; governance by spectacle.

Delhi, bursting at the seams with nearly 30 million people, is hardly home to any. In the past five years, housing prices in Delhi–NCR have surged by more than 80% while incomes have barely kept pace. By any standard of decent living, the monthly minimum wage for a worker of Rs 18,456 falls woefully short of covering the cost of healthy diet, safe housing and living expenses. This summer, as temperatures breached 50 degrees Celsius, threatening the scientific limits of human survivability, dozens of outdoor workers died of heatstroke while new-age apps cracked the whip on the precariat — delivery riders pedalling through the furnace to bring water and food to air-conditioned doorsteps.

Those were the targets of the chief minister’s much-lauded “cleanliness” drive, implemented with ferocity weeks into taking office: bulldozers and municipal teams clearing hawkers, street-food stalls and informal vendors in the name of beautification – a final erasure of the poor, those same poor whom, two years ago, huge billboards were erected to hide from visiting G20 delegates. This weekend, as the air thickened to “hazardous” levels, parents and activists who gathered at India Gate to demand their children’s right to breathe were swiftly detained by police for assembling without permission.

Yet the air, for all its poison, remains stubbornly democratic. It moves across Lutyens’ Delhi and bastis alike, through parliament and pavement. It is the one insurgent left in the city, the last reminder that nature cannot be negotiated with.

But a public so long deprived of any sense of the commons cannot easily muster what it means to fight for one. In Brazil, a modest rise in bus fares in 2013 sparked a nationwide movement against inequality and urban neglect, forcing cities to confront questions of public transport, housing and rights. In Chile, a 30-peso increase in Santiago’s metro fares in 2019 set off the Estallido Social — a revolt that began in the stations and spilled into the streets, demanding a new constitution to dismantle decades of privatisation, from pensions to water. Both began with the right to move, and became struggles for the right to live.

To hold the government to account for our city, we must first have a conception of the city as ours — all of ours. That idea has been quietly dismantled, sold off square foot by square foot, as a depoliticised middle class and a repressed working class together produce what Delhi looks like today: a city choking in silence.

For India to survive, politics must breathe again.

Varsha Gandikota-Nellutla is the General Coordinator of the Progressive International.

Photo: PTI/Karma Bhutia