Introduction

Not all protests are equal. Iran is frequently spoken about as a site of protest, yet rarely understood on its own terms. To analyze collective action without interrogating who authors it, who leads it, and whose interests it ultimately serves is to abandon materialist analysis in favor of abstraction. For Iran, this distinction is existential.

On 9 December (18 Azar), 5,000 contract workers from the South Pars Gas Refinery — one of the most strategic sites of wealth production in the country — took to the streets in one of the largest labor mobilizations in post-revolutionary Iran. These workers represented a broader union of approximately 15,000 workers and, for the first time, carried out a direct action in front of the governor’s office in Asaluyeh, located in one of Iran’s most sensitive and security-intensive provinces. Interviews conducted with participants — and speeches made by the lead organizers — reveal the South Pars workers’ action as an instance of class sovereignty in the form of an Independent Protest — advancing demands within a revolutionary state that remains structurally vulnerable to imperial interference.

This mobilization occurs within a context of a prolonged hybrid war against Iran. For over four decades, the country has faced comprehensive sanctions designed to cripple its economy designed to create conditions for revolt and turn its people against the state. Iran confronts regular acts of sabotage targeting its infrastructure, assassinations of scientists and officials, and cyber attacks on critical systems. Western powers and regional allies have funded and armed separatist movements and radical anti-state groups seeking to destabilize the country from within. Perhaps most insidiously, legitimate social protests have been systematically and ritually co-opted and amplified by foreign media and opposition networks — often with direct ties to intelligence agencies — in attempts to weaponize internal contradictions against the revolutionary state. This hybrid warfare strategy aims to cleave the people from the state, fragment national unity, and create conditions for regime change. Understanding Iranian labor struggles requires recognizing this context, where every internal contradiction becomes a potential entry point for imperial intervention.

Unlike Western frameworks of protest and civil disobedience, or externally-manufactured movements designed to fragment national sovereignty and social formations, the South Pars mobilization demonstrates that resistance within a state forged through popular revolution and committed to anti-imperialism requires a set of principles and practices distinct from those practiced in the imperial core. Here, the measures of success, organizational formations, and strategic interventions aim to sustain national sovereignty, advance anti-imperialist struggles regionally, and address local social and economic contradictions. In Iran, class-conscious labor action is simultaneously a defense of the country’s independence and a site of collective political struggle, distinct from both Western liberal imaginaries of protest and externally-mediated regime-change operations.

What unfolded in Asaluyeh was not merely a labor strike. It was a demonstration of working class sovereignty, anti-imperialist political agency under imperial siege; a collective articulation of rights that refused both submission and chaos, and a living rebuttal to imperial narratives that conflate sovereignty with repression and resistance with disorder.

As an organizer with over a decade of experience across Turtle Island (North America), I write this essay for other organizers, as well as movement leaders, students, and scholars seeking to ground their international solidarity in anti-imperialist and class-conscious practices. I draw on field observations in Iran, documenting how organized labor and collective class struggle are produced, articulated, and sustained by those who live and lead them, offering insight into the strategies, discipline, and principles that enable worker action under conditions of imperial siege, without reproducing or legitimizing the mechanisms of imperial domination. For those situated in the imperial core, I offer a lens for reflecting on positionality, complicity, and responsibility, and for understanding how to practice solidarity with Global South struggles without reproducing the violent agendas of their own states against the sovereignty of other nations.

This essay works through five interconnected features of this struggle: the relationship between workers and law enforcement, the workers' organizational practice and political consciousness, the role of families in protest, women's political agency, and the union as institutional infrastructure. Each dimension reveals a different facet of the same underlying reality: that class struggle in a revolutionary state under imperial assault requires forms of organization and political practice fundamentally different from those in the imperial core. Together, these five dimensions reveal what working-class sovereignty in Iran looks like in practice.

1. The Police

Understanding working-class sovereignty requires careful attention to how the South Pars workers engage with and relate to state power, particularly with the police.

In much of Western political thought and within organizing cultures and spaces shaped by settler-colonial policing, the police are correctly understood as inherently violent institutions designed to repress movements in sustaining the capitalist imperial order. This understanding, while grounded in material histories of racialized and class violence and colonial and imperial repression, becomes a-historical and Eurocentric when universalized.

In the imperial countries, the police function as the domestic arm of the empire. They suppress dissent, criminalize resistance, and enforce accumulation through violence particularly against Black, Indigenous, and other Peoples of Color. I have witnessed this firsthand — from New Haven police trained by the Israeli military violently dismantling Palestinian solidarity encampments at Yale University, to coordinated crackdowns on anti-war organizing in Ottawa. Policing is inseparable from imperial and colonial violence.

In Iran, the Law Enforcement Command exists within a radically different context: a state born of popular revolution, subjected to decades of sanctions, assassinations, sabotage, and overt military threats. Crucially, it faces sustained attempts at regime change operations and color revolution tactics aimed at disarming the state internally by delegitimizing its capacity to maintain order.

The “Woman, Life, Freedom” events marked a decisive moment in this strategy. What emerged as a set of legitimate social grievances was rapidly appropriated and rearticulated — through overt Zionist endorsement, coordinated diasporic networks, and sustained media warfare — into a regime-change project. Policing institutions were not simply challenged as sites of repression; they were rendered legitimate targets of physical elimination. Attacks on officers escalated from confrontation to organized lethal violence, including public executions. This violence was then discursively normalized and, at times, explicitly legitimized within Western corporate media ecosystems, while being materially and logistically amplified by opposition figures, including those associated with Mossad and the CIA. Such violence operated to erode the state’s monopoly on force, fragment institutional authority, and produce conditions conducive to external intervention.

"The workers positioned themselves as custodians of national sovereignty."

Against this backdrop, what unfolded in Assaluyeh was instructive.

Despite a heavy police presence and early-morning roadblocks — largely the result of employer pressure from an oligarchic oil and gas sector empowered by sanctions — the conduct of law enforcement was facilitative rather than repressive.

As the protest unfolded and numbers swelled — eventually nearing five thousand — the police recalibrated. Roads were opened. Fences were removed. The police recognized an indigenous, disciplined, non-violent movement grounded in legitimate constitutional claims. They understood their role not as suppressors of the people, but as guarantors of public order for the people. Chants of “Nirooye Entezami, Tashakor Tashakor” [Thank you, Law Enforcement] echoed through the streets. What emerged clearly, both from the march itself and from the interviews, was that the workers did not see the police as their class enemy.

The workers believed that to delegitimize the law enforcement of a revolutionary state under siege is to reproduce the very logic imperialism uses to justify invasion and collapse. The same discourse that labels anti-colonial resistance as “terrorism” seeks to strip sovereign states of their right to self-defense — internally and externally.

Order, in this context, is the condition for struggle.

2. The Workers

If the workers’ interactions with the police constitute one dimension of working-class sovereignty, the character of the workers’ movement embodies another.

The South Pars protest was, first and foremost, a workers’ movement built, led, and advanced by workers themselves: organized, disciplined, and historically conscious. Its demands did not emerge from alliances with the employer or local bourgeoisie or foreign-funded oppositional media, diasporic elite interventions, or academic centers in the imperial core that materially and ideologically sustain genocidal projects through their institutions. Rather, these demands arose from the lived contradictions of labor within Iran’s most strategic economic sector.

"Imperial protest formations... operate through the strategic separation of people from the state."

Unlike protests engineered or instrumentalized by imperial powers to provoke rupture, spectacle, violence, or advance regime change, this mobilization was rooted in continuity with the Islamic Republic revolution’s unfinished promise of social justice; with the constitutional recognition of labor rights, and with a collective understanding of Iran’s position under sustained imperial siege — from sanctions to overt acts of military aggressions.

The workers positioned themselves as custodians of national sovereignty. This distinction is fundamental. Imperial protest formations, historically visible in Iraq, Libya, Syria, and more recently under the banner of “Woman, Life, Freedom” in Iran — operate through the strategic separation of people from the state, through inciting violence, and by hollowing out national institutions in the name of abstract notions of liberation.

As tensions rose and law enforcement initially attempted to prevent the march and sit-in in front of the governor’s office, Alireza Mirghaffari, president of the workers’ union, placed the highest provincial authority on formal notice. Addressing the crowd, he declared that “the governor had been warned and formally charged with responding to workers’ demands and holding negligent and corrupt officials accountable.” “Should these demands remain unmet,” he stated unequivocally, “the governor himself would be subject to collective accountability by the workers.”

This stance was uncompromising in substance yet principled in form. From the outset, Mirghaffari explicitly not only established a rule of zero confrontation with law enforcement. The organizers also actively worked with and thanked the police for clearing the roads and allowing the march to take place with no conflict — while pushing the boundaries the police had set. When asked about this strategy, Mirghaffari explained that “violence would only serve external actors seeking to hijack the movement for regime-change objectives, as well as domestic actors eager to securitize a fundamentally labor-based struggle in order to suppress it.” The promotion of violence, he emphasized, “has repeatedly proven beneficial to foreign interventionist agendas and detrimental to working-class movements.” The union, therefore, refused to allow any channel, internal or external, to penetrate, redirect, or delegitimize their struggle.

At the end of the protest, Mirghaffari approached the commander, demonstrating a gesture of profound respect telling him “your uniform is sacred to me.” The act constituted a recognition of the structural necessity and legitimacy of the national security apparatus in a country where protests are frequently instrumentalized as tools of regime change against its popular revolution.

The slogans chanted — most notably, “To steal the worker’s wage is to betray the country” — further constituted collective political analysis. Workers saw exploitation not only as class theft but as national sabotage. In a sanctioned economy under constant external assault, defending workers’ rights becomes an act of defending sovereignty itself.

In the days that followed, as anticipated by the union’s leadership, there were multiple failed attempts to appropriate and reframe the protest. These efforts were led by Western-Zionist-funded Persian-language media outlets, including BBC Persian and Iran International, as well as official accounts affiliated with the United States government. These efforts directly contradicted the movement’s stated objectives and principles.

Mirghaffari responded firmly and publicly to the US government Farsi account on X, safeguarding the autonomy of the workers’ movement and rejecting external interference. In response to a statement issued by the US government, he declared that “the term ‘regime’ more aptly described the genocidal American state, not a government born of a popular revolution. Iranian workers have no need for the support of a government complicit in genocidal violence and dispossession. Do not appropriate our voices.”

This episode demonstrates that class struggle remains the primary terrain of political contestation, and that it cannot be meaningfully advanced outside the framework of national sovereignty. The South Pars workers showed that principled, organized labor, rooted in anti-imperialism, anti-capitalism, constitutional legitimacy and revolutionary memory, constitutes its most vital defenses.

In safeguarding their movement, the workers demonstrated and materially practiced what has long been absent in many labor struggles elsewhere: principled risk-taking under conditions of genuine precarity. All participants were among the 15 thousand contract workers, aware that participation exposed them to the possibility of job loss, blacklisting, or disciplinary retaliation, outcomes that had occurred in previous rounds of protest in earlier years. Yet this structural vulnerability did not deter them. On the contrary, it deepened their commitment to collective struggle.

This stands in stark contrast to conditions of struggle in the imperial core. There relative material comfort, often secured through violent exploitation and dispossession of the periphery, has produced political paralysis — including during the ongoing genocide in Gaza. In these economies, the fear of job insecurity disciplines labor into compliance with systems of colonial and imperial violence, compelling workers to continue producing and circulating the very instruments of war that sustain global aggression. The refusal to disrupt production, even when labor is directly implicated in mass killing, is not an ethical failure alone; it is a structural outcome of imperial political economy. Western labor, incorporated into circuits of surplus extraction from the periphery, becomes materially complicit in the dispossession and immiseration of southern working classes. As Ali Kadri has argued, “the struggle today is no longer confined to demands for an eight-hour workday in the core; it is a struggle to ensure that shorter working hours in Europe do not translate into shorter lives in Zimbabwe”.

This orientation toward sacrifice decisively reshapes the strategic form of protest. Whereas labor action in the imperial core often treats the cessation of production as the ultimate horizon of struggle, South Pars workers have consistently articulated a different calculus. While halting substantial segments of operations, they have publicly declared their refusal to interrupt gas production in ways that would endanger public life, particularly during winter, or destabilize the national economy. Disruption is calibrated to impose serious inconvenience and economic pressure on the employer without undermining the material conditions of collective survival or the broader project of national sovereignty.

Such a praxis can only be understood within a state forged through popular revolution and subsequently subjected to sustained imperial assault. Protest under conditions of sanctions, war, and regime-change pressure cannot, and should not, mirror the organizational forms, success metrics, or strategic imaginaries developed in the imperial core. To evaluate such movements through Western liberal or NGO-derived standards is not merely inadequate; it is analytically incoherent.

The South Pars mobilization thus offers a historically significant example of working class sovereignty: a mode of class struggle that simultaneously confronts exploitation, defends national independence, and functions as a site of collective political education.

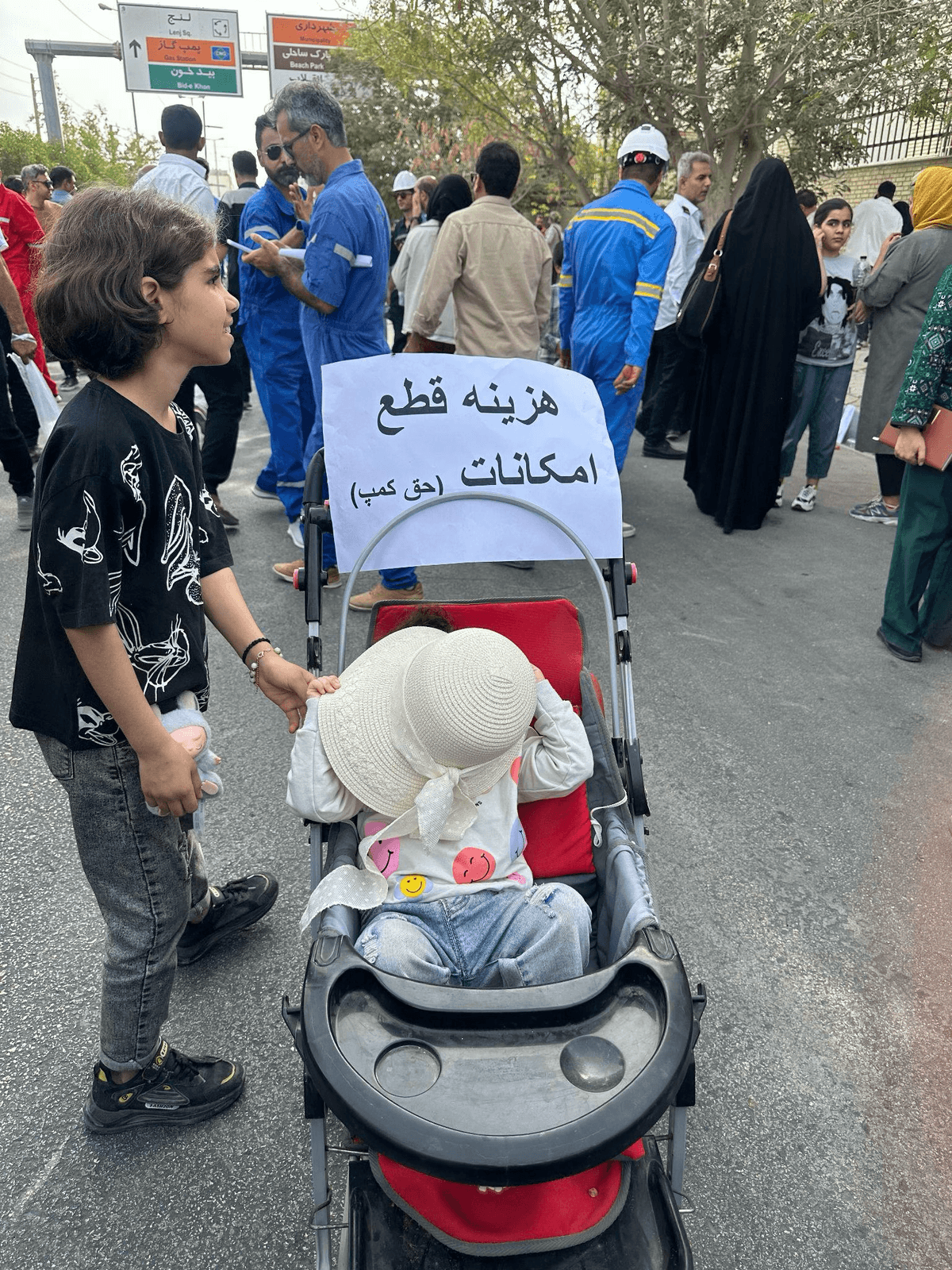

3. The Family

Equally significant to the class composition of the South Pars mobilization was the visible and deliberate presence of families, particularly children, as active participants in the protest. From toddlers as young as three years old to teenage high school students, families arrived together. In recorded calls to mobilize issued by the leadership of the workers’ union — including its president and members of the national executive, workers were explicitly invited to attend with their families. The participation of families was a political strategy.

This strategy operated on multiple levels. First, it functioned as an intergenerational transmission of motalebegari, collective, lawful demand-making, understood not as spectacle or disruption but as civic responsibility. Second, the workers articulated labor justice as a social and moral imperative rather than a narrow economic claim. Demands for fair wages, humane schedules, and job security were consistently framed as essential to the stability of nezām-e khānevādeh (the family order). By anchoring labor claims in household well-being, the protest aligned labor rights with core Iranian cultural and Islamic values.

As a participant-observer, I was struck by the degree of mutual recognition that emerged between protesters and law enforcement. Parents allowed their children to move freely — playing, weaving through the crowd, and at times approaching armed officers — within a gathering that eventually exceeded five thousand people. This was an index of a shared political literacy. The protesters understood how to advance their demands without being instrumentalized as a threat to national security, while law enforcement, in turn, recognized the mobilization as an indigenous, class-based protest not designed to fracture state capacity but to articulate legitimate social claims from within it. This reciprocal calibration produced a palpable sense of collective safety.

This contrasts sharply with protests in the imperial core, where policing typically signals imminent repression. In Assaluyeh, police presence did not function as a blunt instrument of class domination but as a mechanism for containing disorder and safeguarding the protest itself. By presenting themselves as productive forces central to the national economy, workers did not reject security; they rearticulated it. Order and protest were thus not antagonistic but dialectically aligned, revealing a form of popular politics in which labor struggle and national stability were mutually reinforcing.

The presence of families constituted a sovereign political act: an affirmation that labor rights, family stability, and national independence are inseparable, and that any struggle oriented toward endurance must be safe, grounded, and transmissible to the next generation.

4. The Women

The role played by women on 9 December in Asaluyeh highlights an additional dimension of working-class sovereignty. Interviews with participants, including spouses of lead union organizers, some attending with children and others without, revealed a shared political clarity. Their presence was framed as a deliberate political act grounded in āgāhi (consciousness), responsibility, and class solidarity. Decisions regarding safety and children’s participation were carefully considered, with several women explicitly linking the presence of police to the security that made it possible to bring their children to the protest.

Concerns about repression were addressed soberly. One woman described initial anxiety that gave way to “an opening of hope” when the protest was facilitated rather than suppressed. When asked about the personal costs of organizing, responses emphasized collective well-being over security: sacrifice was understood as a structural condition and necessity of resistance under imperial siege and domestic profiteers.

"Organized labor in Iran today opposes not only capital, but also the entire political economy shaped by imperialism’s hybrid war."

Women also drew a sharp distinction between indigenous, class-based struggle and externally mediated protest. Sovereignty movements, they argued, emerge bi-vāsete (without mediation) from the people themselves and aim at improving material conditions rather than producing spectacle or regime change. Workers, as one interviewee noted, “are those who materially sustain the nation; strengthening their conditions necessarily strengthens society as a whole.”

Across narratives, women consistently rejected foreign and Western intervention, identifying such involvement as an attempt to appropriate an indigenous labor struggle for imperial ends — enabled in part by the marginalization of labor issues within domestic Iranian media and the active dismissal of the state to hear their grievances. What unified their accounts was a prioritization of collective reproduction over individual self-realization. Wearing diverse forms of Hijabs, these women rejected liberal feminist reductions of emancipation to bodily symbolism. For them, liberation is found in dignified wages, job security, safe and dignified working conditions, and a future not subordinated to imperial extraction.

In Assaluyeh, women’s political agency directly contests the universalist claims of Western feminism, affirming that women’s emancipation is inseparable from class struggle, anti-imperialism, and Iran’s national sovereignty.

5. The Union

This anti-imperialist, class-conscious political practice, together with the central role of families and the political agency of women, is the product of years of sustained union organizing, making the Association of Trade Unions of Bushehr Refinery Workers (ATUBRW) the institutional backbone of working-class sovereignty in Iran.

Contrary to dominant narratives portraying labour as absent or illegal in Iran, the ATUBRW operates within the constitutional guarantees of Article 26. Representing some 15,000 contract workers in South Pars, it is the largest, most institutionally powerful, and significant union in the country. Importantly, it is also one of the few independent unions whose leadership remains uncompromised and does not collaborate with employers against the collective interests of its members.

What became evident through engagement with the South Pars union was the sophistication of its strategy. Even after prolonged episodes of mass violence and dispossession, many Western labor formations have proven unable to mount general strikes, impose meaningful disruption, or consistently integrate internationalism into their strategic horizon. The South Pars union pursues workers’ rights through a systematically articulated, multi-scalar strategy. At the local and workplace level, this takes the form of sustained workplace-centered action; organizing and collective action, exemplified by the 9 December (18 Azar) protest and ongoing struggles over wages and working conditions. At the national level, the union has intervened directly in political arenas, most notably through a multi-year minimum wage campaign that achieved significant gains, alongside engagement with Majlis representatives and the production of analytical scholarship and political education. Simultaneously, the union has maintained an internationalist orientation, participating in transnational solidarity initiatives — such as co-organizing fundraising for Gaza, and demonstrating a conception of labor responsibility that extends to national defense and social continuity including during the 12 days war of aggression against Iran. during moments of crisis. Taken together, this tri-level praxis reflects a form of labor politics oriented toward the durable construction of collective power across local, national, and global terrains.

"Genuine solidarity requires first recognizing that state sovereignty is not an obstacle to liberation but its precondition — particularly for nations under imperial assault."

Another feature of the South Pars union is its strategic and sustained engagement with the law. Rather than treating legality as a constraint, the union deploys it as one instrument among many in advancing collective struggle. As one lead organizer explained, all formal legal channels were systematically pursued, including the filing of official complaints to substantiate workers’ claims. A landmark outcome was the enforcement of a long-mandated job classification framework that had remained unimplemented for decades, resulting in the systematic denial of workers’ benefits. Through coordinated pressure, the union compelled judicial review in the Administrative Justice Court, culminating in Verdict 3188, which affirmed that workers’ wages must be calculated in a manner that fully reflects the real conditions, responsibilities, and demands of their labor, rather than being narrowly restricted to a minimal rate. When implementation lagged despite the ruling, the union escalated through organized protest and direct action to compel enforcement, demonstrating a praxis that integrates legal struggle with collective mobilization rather than subordinating one to the other.

The challenge for the workers is less a lack of legal frameworks, and more the absence of accountability, monitoring, and the willingness of both the state and the powerful private sector to implement the law.

Conclusion

Organized labor in Iran today opposes not only capital, but also the entire political economy shaped by imperialism’s hybrid war. Independent unions confront a domestic capitalist class whose accumulation strategy is premised on labor fragmentation, depressed wages, and precarity, rendering organized workers an existential threat. Worker exploitation is foundational to the reproduction of power under contemporary conditions.

Sanctions have been central to this class dynamic. They serve not only as an instrument of economic warfare. They are also a mechanism for restructuring domestic class relations. By restricting access to capital, markets, and global circulation, sanctions generate uneven accumulation and empower an oligarchic capitalist faction that operates as an extension of Western capitalism rather than its opponent. Through privatization, asset stripping, and privileged access to state-mediated rents, this class consolidates monopolistic control over strategic sectors of the economy, translating economic dominance into political power. Sanctions thus facilitate the consolidation of a comprador-national bourgeoisie whose accumulation is grounded in scarcity, dispossession, and the intensified exploitation of labor — while simultaneously hollowing out popular sovereignty by subordinating social reproduction to elite accumulation.

This contradiction drives the practice of the South Pars workers. Their struggle is informed by a clear understanding that strengthening the country’s productive forces strengthens national sovereignty, and that sovereignty, in turn, expands Iran’s capacity to resist imperial domination beyond its borders. Labor struggle is thus understood as a contribution to national endurance and geopolitical autonomy. This orientation stands in sharp contrast to recent unorganized street mobilizations, often led by commercial intermediaries and speculative classes, which proved highly vulnerable to infiltration and were rapidly reframed in Western media as regime-change protests. While such mobilizations secured immediate concessions, such as tax exemptions, the South Pars workers’ most recent campaign has been met with silence from both employer and state, and in some cases with punitive wage cuts following the 9 December (18 Azar) protest.

Yet it is precisely under these conditions of neglect and repression that the historical significance of the South Pars union becomes clearest. Despite the absence of immediate gains, it remains the leading force of independent labor organizing in Iran, offering a living example of how to conduct protest with dignity, discipline, and class consciousness in a country subjected to imperial violence. What makes this movement progressive is its integration of labor struggle, national sovereignty, and international solidarity. By situating workers’ rights within a transnational anti-imperialist horizon, linking Iranian labor to struggles from Gaza to Venezuela, the union articulates a politics in which defending wages, enforcing legal protections, and consolidating workplace power are inseparable from resisting imperial domination and advancing collective emancipation.

In this sense, South Pars represents both a pedagogical and political intervention into the meaning of protest itself. It shows that under conditions of imperial siege, the most radical form of struggle is one that simultaneously confronts exploitation, defends national sovereignty, and builds the material foundations of revolutionary endurance. For movements organizing in solidarity with the Global South from within the imperial core, the South Pars struggle carries clear and urgent implications. Genuine solidarity requires first recognizing that state sovereignty is not an obstacle to liberation but its precondition — particularly for nations under imperial assault. Organizations, trade unions, and movements must actively combat sanctions regimes that devastate ordinary working people while often empowering national bourgeoisies. This means building direct relationships with formations like the South Pars gas workers' union, learning from their practice, and amplifying their voices without appropriating or distorting the terms of their struggle. It means resisting the seizure of Iranian assets abroad — billions of dollars of public wealth stolen, which erodes the state’s capacity to provide for its people. And it means refusing any collaboration with the Iranian opposition's alliances with far-right forces and Zionist networks abroad, recognizing these alliances as fundamentally incompatible with anti-imperialist struggle.

Dr. Helyeh Doutaghi is a scholar of international law and political economy. She is currently a postdoc fellow at University of Tehran, working on her manuscript focusing on the impact of sanctions on the Iranian working class. She is an organizer with over a decade of experience across Turtle Island (North America), including sustained involvement in student, labor, anti-war and anti-sanctions, and Palestinian liberation movements. Dr. Doutaghi is also on the Steering Committee of the People’s Academy.