First published in Issue 40 of The Internationalist.

Following a violent dispersal of the Qiyada sit-in in 2019, known locally as the 3 June massacre, a 3-year Transition Military Council (TMC) was agreed upon despite ongoing protests and proposals for alternative charters that speak to the demands of the uprising, such as the Charter of the United Cities of Sudan. The TMC was to be shared between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) headed by Abdel-Fattah al-Burhan, his right-hand man, head of the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, or Hemedti, and Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok.

The Military Council was supposed to share power with civilian forces in the so-called Transitional Sovereignty Council. But over a year and a half into this period, in the early morning of 25 October 2021, the SAF and RSF led a joint coup dissolving the transitional government and arresting the prime minister and his cabinet. Since then, on 15 April 2023, a power struggle between the SAF and RSF, which gained influence and power under al-Bashir’s Islamist regime, has led to the eruption of a violent war.

To date, reported violations committed by the warring parties include, but are not limited to: a growing number of sexual violence cases against women and children; the occupation, looting and destruction of people’s homes, historical archives and public buildings across the tri-city state of Khartoum (some of which are recorded under the hashtags #الدعم_السريع_يستبيح_بيوتنا and #RSF_loots_houses); the complete destruction and burning of entire villages and towns across Darfur; RSF abduction of civilians from streets, homes, transport vehicles, public service buildings such as hospitals, and taken to makeshift holding prisons across the city’s forcefully emptied buildings and kept for days, weeks, or months.

According to the IOM’s 15th Sudan Situation Report, over 3 million people have been displaced primarily from Khartoum and Darfur states, with over a quarter of those seeking refuge across borders in neighboring countries such as Egypt, Chad, South Sudan, Ethiopia and others. Many who sought refuge across national borders have been met with continuously changing border regulations that have left people stranded for days, weeks, and in many cases, months. Along the Egyptian borders, for example, reports have shown that this approach of extreme border surveillance partially stems from projects funded by the EU since 2015 as part of their border externalisation policies.

Those who have not crossed national borders have sheltered in place (remaining in areas of conflict by choice or out of necessity) or in neighboring states within the country. A large number of those displaced are sheltering in households with host communities who have generously opened up their homes to family, friends and strangers alike. The remaining population is dispersed between newly rented accommodations, displacement camps set up by various aid and grassroot organisations, schools and other public service buildings, and settling improvised shelters in open areas. In all these cases, the prolongation of the conflict from a few days to over four months with an unforeseeable future, has put immense financial and supply strains on both displaced and host communities as rent, food, medical supplies, and other commodity prices continue to skyrocket in an unregulated financial market. Additionally, as the rain and flood season slowly creeps in (typically the months of June – September), reports warn about the damaging impacts, such as disease outbreak, in areas already susceptible to heavy rains and flooding.

Throughout the whole revolutionary period, however, the Sudanese people were under no illusions about the nature of the military regimes, and continued organising themselves at the grassroots forming the so-called Resistance Committees.

Resistance committees grew from neighborhoods across Sudan in 2013, and gained momentum in their efforts to organise protests in 2019. Over the following years, they grew in number and role, expanding their efforts to organically respond to the needs of their neighborhoods and the continuously shifting political climate. Despite the coup d'etat leaders and international actors once again sidelining the people’s demands for civilian rule, resistance committees rejected any calls for negotiation with the coup parties under the principle of the three no’s; no negotiations, no partnership, no compromise. Instead, more than 8,000 Resistance Committees, trade unions and women’s groups around the country took part in co-constructing the Revolutionary Charter for Establishing People’s Power.

As over 100 days of war between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Security Forces (RSF) have left Sudan and its people in an unpredictable state, resistance committees have started operating emergency rooms around the country at times located in highly volatile places. Collaborating with all forms of local organizations and volunteers, these spaces have been key for assessing local needs, providing services and finding the people to provide them..

For issue #40 of The Internationalist, Ahmed Ismat, the spokesperson of Resistance Committees of Khartoum, discusses the roots of the current conflict in British colonialism, the role of resistance committees in providing direct aid and upholding the demands of the revolution, and the dream of a peaceful and democratic Sudan. If anything, this unfolding of events showcases how revolution is not a singular event, but an ongoing and continuous process.

We are past the 100th day of the war raging in Sudan since the weekend of 15 April 2023, when the simmering conflict between the Sudanese military and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) broke out into open warfare. Since then, thousands have been killed and over two million people have been displaced internally and many more in neighbouring countries. How did it come to this escalation?

This is a very tough question. But when we speak about Sudan, the root cause of all of our problems emerged from the British colonialist state apparatus. It created an uneven system with heavily exploited margins, which led to violence becoming a means of production.

Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, or Hemedti – the leader of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and first deputy head of the Transitional Military Council (TMC) following the 2019 Sudanese coup d'état – emerged from and grew within these contradictions, and he was used by the Islamists to crush political dissent in the west of Sudan since 2003.

During the sit-ins in April 2019 after we overthrew Bashir – the former 30-year military president of the country – the political elite who used to lead the protests chose to side with Al-Burhan, head of SAF and chairman of the TMC, Hemedti and the council. They gave this council legitimacy just by sitting down to negotiate with them, a council who’s members had not been held accountable for the numerous crimes they had committed. The voices opposing these negotiations grew after the RSF shot at peaceful protestors on the 8th of Ramadan during the sit-in, followed by the infamous massacre on 3 June 2019 where more than 120 peaceful protestors were killed and thrown into the Nile.

While we didn't give up and millions came back out on the streets again to protest on 30 June 2019, the civilian elite – like the Forces of Freedom and Change (FCC) – continued to negotiate with the warlords and ‘share’ power in the intended three-year Transitional Sovereignty Council. In this way, a transitional government was formed in 2019. It was because of international pressure that the political power-sharing agreement in a transitional government with the military in 2019 came into existence – against the people's wishes. There were also multiple calls after the October 25 coup from the United Nations’ Special Representative for Sudan, Volker Perthes, for “peace negotiations” that would bring the army and the resistance committees around the table, particularly after we had gained significant momentum and political organization after the coup. This led to the committees releasing what was known as the three no’s; no negotiations, no partnership, no compromise. Our position was against sitting around the same negotiation table with warlords and those who had not been held accountable for killing our brothers and sisters across Sudan and during the violent dispersal of the 2019 sit-in.

We kept protesting throughout this whole time, before and after the military coup on 25 October 2021. Although we kept demanding justice by calling for the dismantling of this militia and bringing its leaders to court, the army and the political elite kept defending and siding with it.

During this period, the RSF managed to usurp offices that had belonged to Al-Bashir’s fallen Islamist regime, including the headquarter that belonged to the dismantled military sector of the National Intelligence Agency. The RSF even took over the air defense headquarters in Bahri (Khartoum North).Throughout this last year, the political scene began to reshape as the ‘civilian’ political elite chose to form an alliance with Hemedti and came out with the so-called ‘framework agreement’. During these negotiations, voices inside the army grew louder against the RSF, and vice versa.

The war broke out, and everyone took a side, beginning with the political elite who until now didn't condemn the atrocities carried out by the RSF. They do not say they support the RSF upfront, but they echo Hemedti’s propaganda and turn a blind eye to the war crimes carried out by his militia, while the Islamists are siding with Burhan and the army generals.

We are against the army’s leadership and the existence of the RSF, but we don’t think that this war will lead to bringing an end to the RSF – given the current leadership and their history with the militia.

You mentioned the role of colonialism in producing Sudan’s current violence and political impasse. Could you explain that in a bit more detail?

Aside from the British using the Sudanese Armed Forces (known then as the Sudanese Defense Forces) in the Second World War, they also mobilized it to crush dissent within the country pre-independence. The British learned something from their other colonies: you can't actually kill and arrest people and expect them to shut up and accept colonialism. They learned that they need a political voice from within to convince the population that colonialism is in their favour, so, they created an armed forces with guns.

Additionally, they also found a strong political voice, people with strong cultural influence in Sudan: tribal and Sufi leaders, which now form the base of some political parties. Recognizing this influence, they were given lands, money, and government power within the colonial machine, and they educated their sons and daughters. With these, their political influence grew. The British basically used those two — let’s call them machines with guns and words. Whenever one of the machines couldn’t finish the job, they went to the other.

When you look at Sudan's first coup back in 1958, the elected civilian leader actually went to the Army and told them to do a coup d’état and gave them the government. You can see this pattern throughout Sudan’s history. All the politicians care about is using the Army, against the other parties.

Other than that, why did the British even invade Sudan? Because they needed raw materials, Arabic gum, gold, men to fight and work, andanything else. The system they created was a system that extracts raw materials fast and in a really exploitive, really cheap way. If you look at Sudan’s balance sheet every year — even after colonialism formally ended — you can see that it didn’t change at all. Everything is sucked out of Sudan: we export raw material and import consumer products. There was one incident where farmers in Dongola (Northern Sudan) protested and closed the only road connecting Sudan with Egypt. Everyone saw with their own eyes that Sudan exports living animals, like camels and sheep, to Egypt, while they import furniture, makeup and other things. The balance sheet is set in a way that the export is made by the margins and the import is consumed by the centre (Khartoum).

The revolution has opened our eyes to the fact that this is happening. We understood and saw how a system like this would create so much tension between the centre and the margins — and within the margins themselves.

What role did international institutions play in Sudan since the revolution and in the attempt to find a lasting and peaceful settlement?

It was because of international pressure that the political power-sharing agreement in a transitional government with the military in 2019 came into existence – against the people's wishes.

The resistance committees came into existence as a protest against the political elite. The revolution gave us back our power to dissent, we felt like we controlled our own destinies. That helps you understand how disappointed we were that the international institutions kept pushing for backdoor deals between the civilian and military elite. Once again, what we have to say about our own future and the policies dictating it didn't matter. But we took that chance to organise and create coordination across the country.

Could you give us a sense of what’s going on right now in Khartoum, and speak about the role the Neighbourhood Resistance Committees are playing in the war?

A lot of Khartoum residents have evacuated from the city and relocated to different countries, states and cities, living as migrants, IDPs or refugees. Many people have lost their homes and their life savings to the RSF. Personally, my house was raided and fully stolen by RSF soldiers. It was used as a base, which they evacuated now. Many people in our neighbourhood died through stray bullets and so on.

I really believe that what the RSF has done to the Sudanese people has affected it irreversibly.

Since the beginning of the war until now, the RSF has given us [civilians] this sense that their main enemy seems to be us, not the army. It’s them who raided homes, raided hospitals, killed innocent bystanders and killed families while they were trying to evacuate. People were much more affected by the RSF, as opposed to being ‘collateral damage’ to a battle between the army and the RSF. I can sense the general anger towards the RSF. I really, really, really, really doubt that — even if they struck a peace agreement — I really doubt that the RSF will ever be accepted by the people again.

What I've seen and what I've heard from people who evacuated and from people who are still in Khartoum (as they don’t have any family outside of Khartoum) it's actually horrific. I don't believe that RSF will be no more after this. This is a radical change in everyone’s perspective of Sudan.

In early June, the UN spoke of concerns about ethnic violence and crimes against humanity, both by the Sudanese Army and the RSF. In mid-July, it was reported that 87 people, including ethnic Masalits, have been found buried in a mass grave in Sudan’s West Darfur, in a crime likely perpetrated by the RSF. What are you witnessing in Khartoum?

When we speak about ethnic violence and crimes against humanity, the RSF takes the lead, of course, because it was founded on everything that's wrong with this country. It was founded on every contradiction in the state. They use a racist or ethnic rhetoric to fuel their propaganda. This has been consistent, even before the war. They have carried out atrocities in Darfur, in North Kordofan, and elsewhere. We have seen this type of violence used in Darfur in the 2013 uprising – and then again in the two massacres on the 8th of Ramadan and 3 June.

The RSF is a huge violence machine. It’s a huge racist machine. It’s a huge money machine. It's a huge mercenary machine. The RSF definitely takes the lead in producing violence in Sudan. The army generals have the same mentality as the RSF generals. However, I wouldn't say that every army soldier has the same mentality as an RSF soldier. It depends on the institution you are in. When it comes to the army, you're raised and trained to fight for the country. This is the type of propaganda and the type of education you get. But with the RSF, it’s about money and power.

What are you doing with the resistance committees in this situation, both politically and practically?

We try to unify behind a really strong political agenda. Our agenda is to bring real democracy to Sudan. That’s what we had in 2019, this was real democracy — real democracy from the people and for the people. We want to abolish all the old institutions and build new ones. The resistance committees came into existence as a protest against the political elite. The revolution gave us back our power to dissent, we felt like we controlled our own destinies. That helps you understand how disappointed we were that the international institutions kept pushing for backdoor deals between the civilian and military elite. Once again, what we have to say about our own future and the policies dictating it didn't matter. But we took that chance to organise and create coordination across the country.[KE3]

Other than that, every resistance committee in every neighbourhood has established what’s called an emergency room. We called upon all the doctors and pharmacists and basically anyone in the medical field to come and help.

We have rebuilt hospitals, making them operative again. Doctors came to work there and gave medical aid for free. We also try to get wheat, bread and so on to make huge feasts for people every day in the neighbourhoods. This is what the emergency room exactly does. Resistance committees outside of Khartoum in other states also formed emergency rooms to be able to welcome migrants, help feed them and give them healthcare.

What would international solidarity with the Sudanese people look like?

A lot of emergency rooms also need help to buy products. They take donations, and they publish what they have spent and how they spent it every day.

The biggest support would be protests against any organisation having any relationship with the RSF to cut off their funding and stop the RSF propaganda machine. For example, Youssef Izzat al-Mahri, one of the RSF’s advisors, was going to give a lecture in Germany and market the organisation, but it was stopped by Sudanese people in Germany because they wrote to the people hosting the lecture and got it canceled.

To learn more and stay up-to-date with what is happening in Sudan, visit the following pages:

List of support initiatives:

Twitter accounts to follow:

- Resistance Committees - https://twitter.com/ResistCommittee

- Gouja Ahmed - https://twitter.com/qoga12

- Ayin Network - https://twitter.com/AyinSudan

- Radio Dabanga - https://twitter.com/RadioDabanga

- Beam Reports - https://twitter.com/BeamReports

- Marwa Gibril - https://twitter.com/MarwaGibril

- Muzan Alneel - https://twitter.com/MuzanAlneel

- Mat Nashed - https://twitter.com/matnashed

- Khuloud Khair – https://twitter.com/KholoodKhair

- Abubakr Omar - https://twitter.com/ThawragySD

Instagram accounts to follow:

- Sara Al Hassan - https://www.instagram.com/bsonblast/

- Project Taghyir - https://www.instagram.com/project.taghyir/

This edition of The Internationalist was produced by Khalda El Jack and Daniel Kopp.

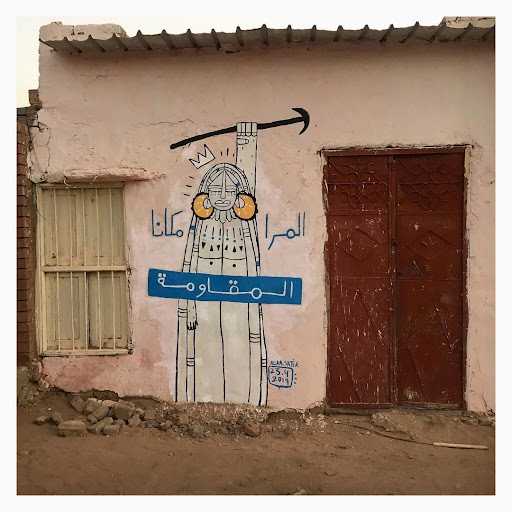

Image: With the words, “A woman’s place is in…the resistance,” Satir’s mural was the first of many murals to highlight women in Sudan and break down the patriarchal belief that women should not be on the streets.