We are not drowning, we are fighting” has become the rallying call for the Pacific Climate Warriors. From UN climate meetings to blockades of Australian coal ports, these young Indigenous defenders from twenty Pacific Island states are raising the alarm of global warming for low-lying atoll nations. Rejecting the narrative of victimisation – “you don’t need my pain or tears to know that we’re in a crisis,” as Samoan Brianna Fruean puts it – they are challenging the fossil fuel industry and colonial giants such as Australia, responsible for the world’s highest per-capita carbon emissions.

Around the world, climate disasters displace around 25.3 million people annually – one person every one to two seconds. In 2016, new displacements caused by climate disasters outnumbered new displacements as a result of persecution by a ratio of three to one. By 2050, an estimated 143 million people will be displaced in just three regions: Africa, South Asia, and Latin America. Some projections for global climate displacement are as high as one billion people.

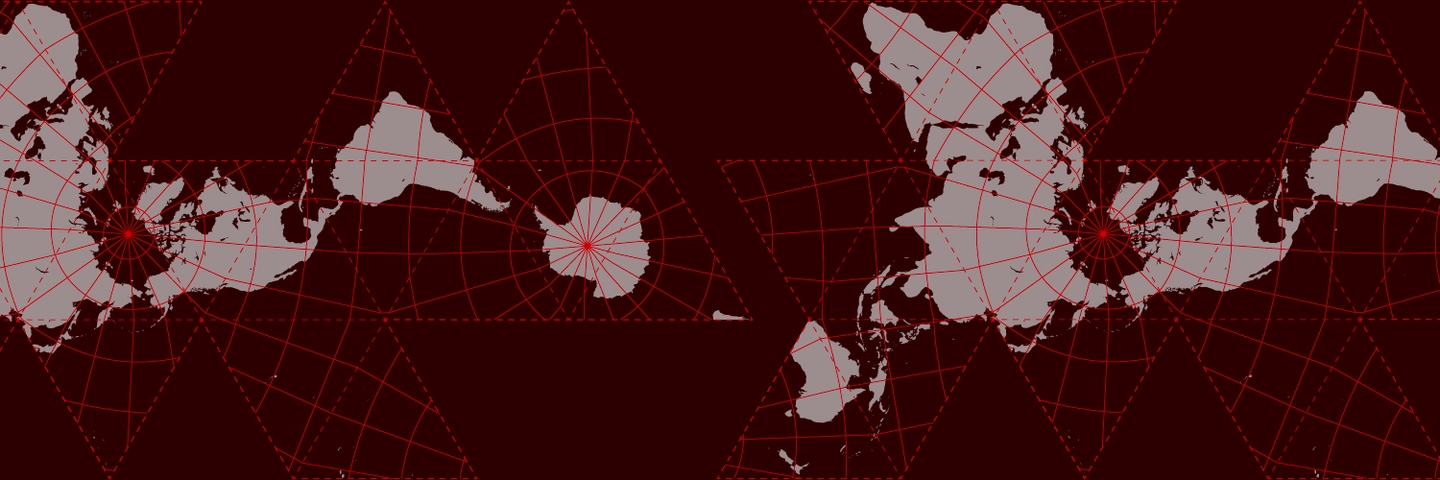

Mapping who is most vulnerable to displacement reveals the fault lines between rich and poor, between the global North and South, and between whiteness and its Black, Indigenous and racialised others.

Globalised asymmetries of power create migration but constrict mobility. Displaced people – the least responsible for global warming – face militarised borders. While climate change is itself ignored by the political elite, climate migration is presented as a border security issue and the latest excuse for wealthy states to fortify their borders. In 2019, the Australian Defence Forces announced military patrols around Australia’s waters to intercept climate refugees.

The burgeoning terrain of “climate security” prioritises militarised borders, dovetailing perfectly into eco-apartheid. “Borders are the environment’s greatest ally; it is through them that we will save the planet,” declares the party of French far-Right politician Marine Le Pen. A US Pentagon-commissioned report on the security implications of climate change encapsulates the hostility to climate refugees: “Borders will be strengthened around the country to hold back unwanted starving immigrants from the Caribbean islands (an especially severe problem), Mexico, and South America.” The US has now launched Operation Vigilant Sentry off the Florida coast and created Homeland Security Task Force Southeast to enforce marine interdiction and deportation in the aftermath of disasters in the Caribbean.

Labour migration as climate mitigation

you broke the ocean in

half to be here.

only to meet nothing that wants you

Nayyirah Waheed

Parallel to increasing border controls, temporary labour migration is increasingly touted as a climate adaptation strategy. As part of the ‘Nansen Initiative’, a multilateral, state-led project to address climate-induced displacement, the Australian government has put forward its temporary seasonal worker program as a key solution to building climate resilience in the Pacific region. The Australian statement to the Nansen Initiative Intergovernmental Global Consultation was, in fact, delivered not by the environment minister but by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection.

Beginning in April 2022, the new Pacific Australia Labour Mobility scheme will make it easier for Australian businesses to temporarily insource low-wage workers (what the scheme calls “low-skilled” and “unskilled” workers) from small Pacific island countries including Nauru, Papua New Guinea, Kiribati, Samoa, Tonga, and Tuvalu. Not coincidentally, many of these countries’ ecologies and economies have already been ravaged by Australian colonialism for over one hundred years.

It is not an anomaly that Australia is turning displaced climate refugees into a funnel of temporary labour migration. With growing ungovernable and irregular migration, including climate migration, temporary labour migration programs have become the worldwide template for “well-managed migration.” Elites present labour migration as a double win because high-income countries fill their labour shortage needs without providing job security or citizenship, while low-income countries alleviate structural impoverishment through migrants’ remittances.

Dangerous, low-wage jobs like farm, domestic, and service work that cannot be outsourced are now almost entirely insourced in this way. Insourcing and outsourcing represent two sides of the same neoliberal coin: deliberately deflated labour and political power. Not to be confused with free mobility, temporary labour migration represents an extreme neoliberal approach to the quartet of foreign, climate, immigration, and labour policy, all structured to expand networks of capital accumulation through the creation and disciplining of surplus populations.

The International Labour Organization recognises that temporary migrant workers face forced labour, low wages, poor working conditions, virtual absence of social protection, denial of freedom association and union rights, discrimination and xenophobia, as well as social exclusion. Under these state-sanctioned programs of indentureship, workers are legally tied to an employer and deportable. Temporary migrant workers are kept compliant through the threats of both termination and deportation, revealing the crucial connection between immigration status and precarious labour.

Through temporary labour migration programs, workers’ labour power is first captured by the border and this pliable labour is then exploited by the employer. Denying migrant workers permanent immigration status ensures a steady supply of cheapened labour. Borders are not intended to exclude all people, but to create conditions of ‘deportability’, which increases social and labour precarity. These workers are labelled as ‘foreign’ workers, furthering racist xenophobia against them, including by other workers. While migrant workers are temporary, temporary migration is becoming the permanent neoliberal, state-led model of migration.

Reparations include No Borders

“It’s immoral for the rich to talk about their future children and grandchildren when the children of the Global South are dying now.” – Asad Rehman

Discussions about building fairer and more sustainable political-economic systems have coalesced around a Green New Deal. Most public policy proposals for a Green New Deal in the US, Canada, UK and the EU articulate the need to simultaneously tackle economic inequality, social injustice, and the climate crisis by transforming our extractive and exploitative system towards a low-carbon, feminist, worker and community-controlled care-based society. While a Green New Deal necessarily understands the climate crisis and the crisis of capitalism as interconnected — and not a dichotomy of ‘the environment versus the economy’ — one of its main shortcomings is its bordered scope. As Harpreet Kaur Paul and Dalia Gebrial write: “the Green New Deal has largely been trapped in national imaginations.”

Any Green New Deal that is not internationalist runs the risk of perpetuating climate apartheid and imperialist domination in our warming world. Rich countries must redress the global and asymmetrical dimensions of climate debt, unfair trade and financial agreements, military subjugation, vaccine apartheid, labour exploitation, and border securitisation.

It is impossible to think about borders outside the modern nation-state and its entanglements with empire, capitalism, race, caste, gender, sexuality, and ability. Borders are not even fixed lines demarcating territory. Bordering regimes are increasingly layered with drone surveillance, interception of migrant boats, and security controls far beyond states’ territorial limits. From Australia offshoring migrant detention around Oceania to Fortress Europe outsourcing surveillance and interdiction to the Sahel and Middle East, shifting cartographies demarcate our colonial present.

Perhaps most offensively, when colonial countries panic about ‘border crises’ they position themselves as victims. But the genocide, displacement, and movement of millions of people were unequally structured by colonialism for three centuries, with European settlers in the Americas and Oceania, the transatlantic slave trade from Africa, and imported indentured labourers from Asia. Empire, enslavement, and indentureship are the bedrock of global apartheid today, determining who can live where and under what conditions. Borders are structured to uphold this apartheid.

The freedom to stay and the freedom to move, which is to say no borders, is decolonial reparations and redistribution long due.

Harsha Walia (@HarshaWalia on Twitter) is the award-winning author of Border and Rule: Global Migration, Capitalism, and the Rise of Racist Nationalism (Haymarket, 2021), and Undoing Border Imperialism (AK Press, 2013). She is a community organiser and campaigner in migrant justice, anti-capitalist, feminist and anti-colonial movements.

Photo: Asian Development Bank / Flickr