History bears witness to a universal truth: The inauguration of the colonial future begins with the erasure of the Indigenous past. In March 2023, as part of an ongoing federal restructuring of the Nepali state, the provincial government of as-yet-unnamed “Province No. 1” of eastern Nepal made the parliamentary decision to name the province, “Koshi”.

The Indigenous Kirat, predominantly the Rai and Limbu ethnic communities, rejected this name on a few important grounds. First, with its mythological origins rooted in Hinduism, “Koshi” represented neither the history nor heritage of the geographic territory. Second, the ruling government had deceitfully deployed their electoral advantage in the provincial parliament to sidestep deliberative dialogue necessary in something as historic as naming a province. In doing so they had reneged on the promises made to the Indigenous people during the election time.

This was how the “No Koshi” Indigenous movement was born; negligible to the state in its nascent phase, but less so after their more-than-expected showing in a recent by-election in one of the important constituencies in eastern Nepal.

At the heart of this ongoing movement is a demand for the right to name one’s territory and land according to the heart’s desire. To put it pointedly, the movement has declared “Enough!”; enough with the project of erasing and replacing Indigenous names of places, landscapes, rivers, forests, graveyards, hills and rocks, with Hindu names, as a primary and preliminary form of neocolonial domination and control. The resurgent “No Koshi” movement is persistent and relentless, not violent but also not peaceful, and filled with creativity deemed necessary to deal with uncertainty.

A motley crew of activists and anthropologists, architects and geographers, photographers and writers, many of us of the Indigenous background, embarked on a journey of eastern Nepal to document the resurgent Indigenous movement carried out in the spirit of critical solidarity with the movement. On the journey, we passed many rivers and their tributaries, hilly mounds and graveyards, ponds and forests. We spoke with young students and activists, political leaders and local historians, returning migrants and farmers who never left. Through their telling, we have come face-to-face with histories, stories and anecdotes that spoke of the sacred bonds people in these parts have historically shared with nature.

So, when names are erased, it is not just the names that are lost. Remembering and forgetting are powerful tools for exerting domination and control. New names remove old traces. And when the past is no longer remembered, what is lost is the legitimacy necessary to make claims over the present time. In turn, what is ultimately taken away, seized under broad daylight, is the power to chart a future.

During the journey, each day left behind an impression that made this clear — after a decade of dormancy, the indigenous movement in eastern Nepal is back at the forefront. And reclaiming the names — of water, forest, and land — that were lost or stolen, effaced or erased, through stealth and by force, was the first fight to be fought, and won, in this permanent war of attrition for reclaiming power.

No Koshi!

In little over a year, the “No Koshi” movement has taken a life of its own. Across municipalities and districts, “struggle committees” — a federated network of place-based collectives of Indigenous peoples — have formed. During this time, the phrase “No Koshi” has become a vibrant discourse, potent enough to galvanize conversations in tea shops and dinner tables, and inspire actions through public assemblies and open seminars. Spread horizontally across towns and villages, these actions resist state and market-led encroachments of Indigenous lands such as concretization of traditional ponds in the name of preservation and beautification; the creation of parks on top of Indigenous burial grounds to purportedly commemorate long-dead politicians that the locals don’t identify with; and the superimposition of Hindu names on top of Indigenous names to erase the traces that connected the Indigenous communities to their ancestry and heritage, to name a few.

What all of this means is this: Initially formed to reject the name “Koshi”, “No Koshi” as a movement has now fully mutated into a potent incubator of counter-politics from below to proactively and creatively resist the erasure of indigeneity in the name of beautification, preservation, commemoration, and more importantly, “development” — the latter, in the shape of an anti-capitalist “No Cable Car” movement.

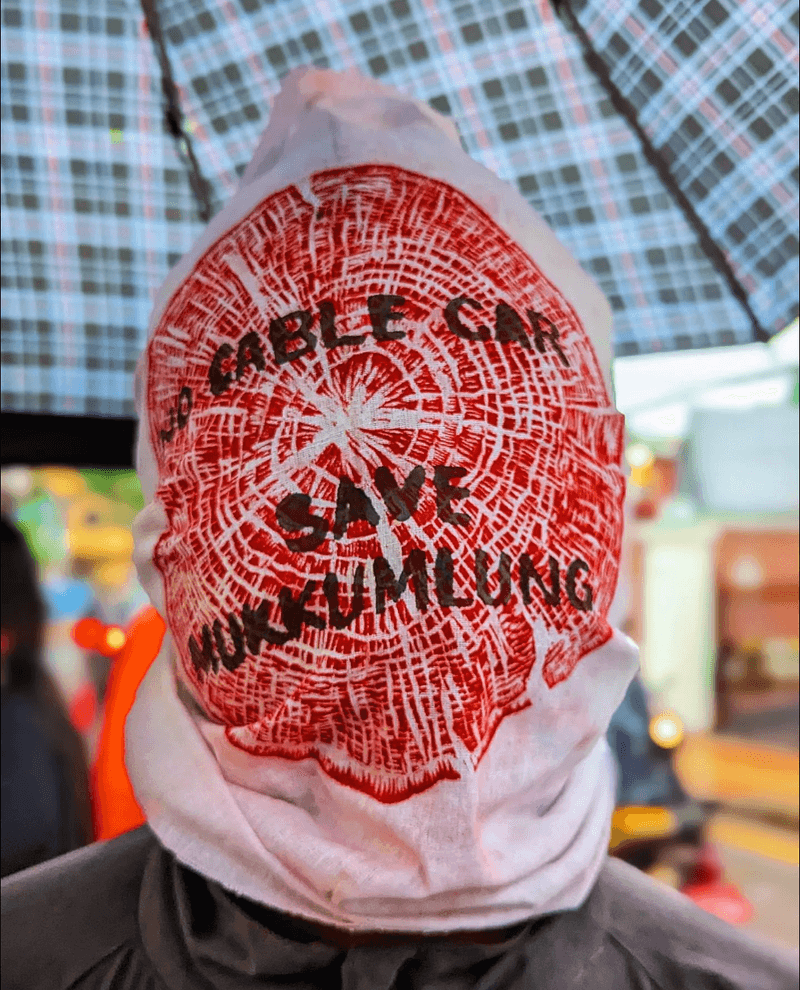

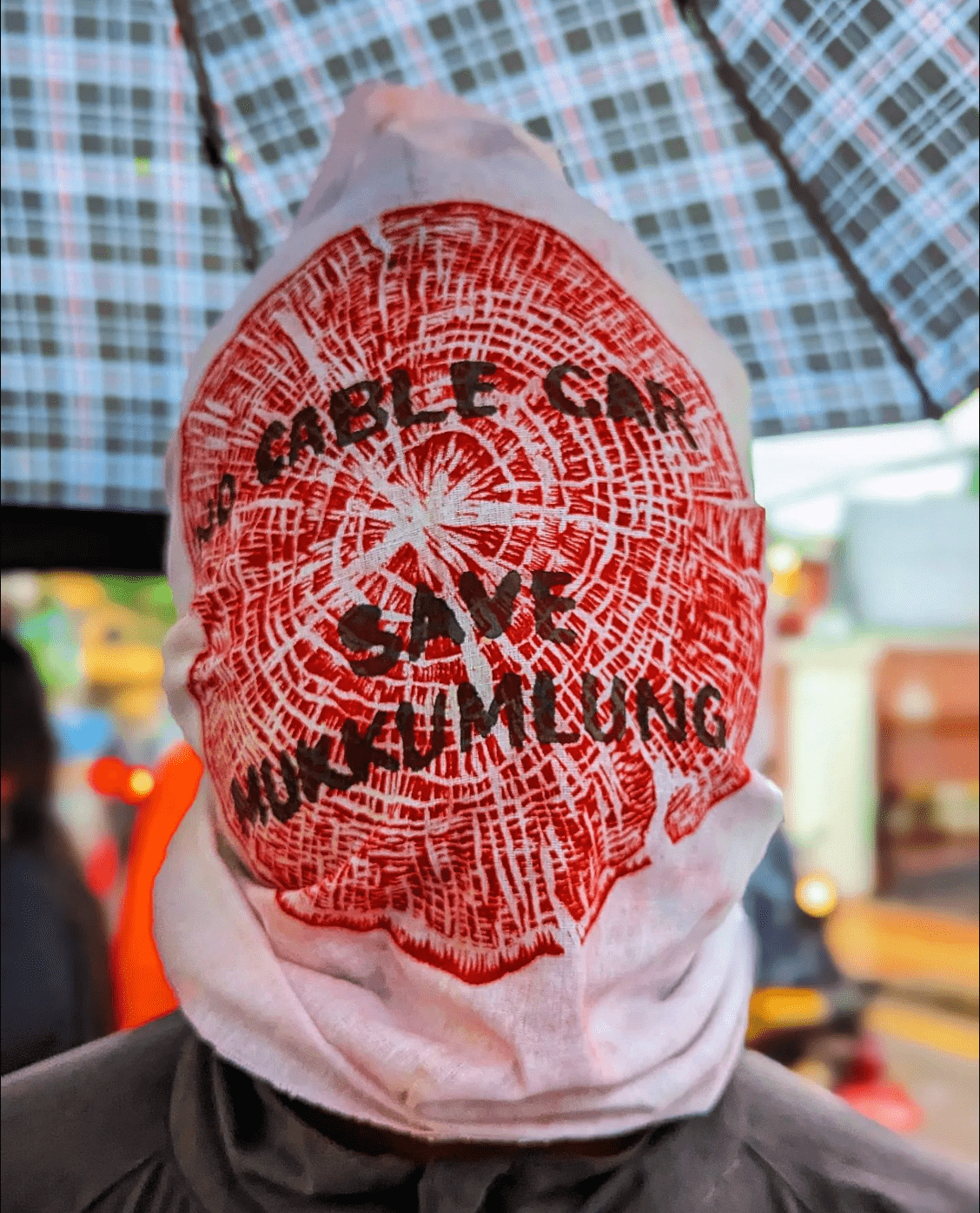

Led by the Indigenous youths that are the frontline protestors and leaders of “No Koshi”, the “No Cable Car” is a focused resistance in defence of what the Indigenous Limbu consider the sacred landscape and the ancestral land — a mountainous biodiversity-rich ecological zone filled with locally-led economy, on top of which a Kathmandu-based business mogul now wants to build a cable car project, threatening to erase both the mountain ecosystem including its local economy, in the process.

“No Cable Car!”

In the early hours of 13 May 2024, the mayor of Phungling municipality, where the “No Koshi” movement is centered, sent his people to the hills to cut down trees. Activists guarding the territory in a tiny settlement along the ridges got wind of it. They jumped out of their beds, climbed up the hill, navigated through the dawn and the thickness of trees, and soon encountered about a hundred individuals hacking the trees down with chainsaws. Amidst the skirmish that followed, the activists chased the tree-cutters away but damage had been done. Hundreds of trees, around for over a thousand years, had fallen.

The cutting down of trees in a militant manner was not a one-off stand-off. Exactly two months before this onslaught on trees, on the 13th of March, a battalion of Armed Police Force (APF) tried to pass through the activists that had formed a human chain at the base of Mukkumlung. The activists, led by Shree Linkhim, a young man in his early 30s leading the movement as the leader of the Mukkumlung Struggle Committee, somehow made the APF retreat and eventually drove down the highway and into their barrack. “It was close. For the standoff to escalate into full-blown violence, only one of us or them had to lose our heads”, said Shree, the day after the incident when we met. No one lost their head.

The trees were cut down to make way for the construction of a private company-led cable car project atop Mukkumlung — a lush green mountain rich in biodiversity, home to endangered animals such as Red Panda and Snow Leopard, filled with trees, mostly Rhododendron, Nepal’s national flower, and a landscape sacred to the Limbu.

Limbu follow Mundhum, an oral tradition of story-telling and performance that speaks of the relationship between humans and nature. According to Mundhum, such a relationship needs to be maintained through an act of balance underlined by justice and dignity — the balance deemed necessary to arrive at Cholung — a utopia. Mukkumlung, a Limbu phrase that translates into English as “center of power”, is popularly known to the Hindu devotees as Pathibhara, the Hindu goddess, which has over time displaced Mukkumlung from popular parlance. This was the beginning of cultural genocide.

The state-led formation of the “Pathibhara Area Development Committee” in 1996 and its revision in 2018 opened the Indigenous territory to private-profit-oriented intrusion in the shape of the cable car project further causing the erasure of indigeneity. Moreover, the cable car project is led by a Nepalese billionaire, Chandra Prasad Dhakal, who owns a national private bank, another cable car company in operation, is the president of the Federation of Nepalese Chamber of Commerce and Industries (FNCCI) and now has his eyes fixated on Mukkumlung for multiplying private profit.

The Indigenous community, alongside small locally-led businesses as well as porters catering to the needs of tourists and pilgrims, resist the “Pathibhara Cable Car Project” on a few important grounds: It is forced from above without any consultation with the local community; it will destroy biodiversity — it will claim more than 13 acres of forest land and over 10,000 trees; it will dismantle local economy — more than 700 local porters and nearly 30 locally-run small businesses; it will displace local communities — nearly 1700 households; and it will destroy history and heritage.

In response to the felling down of trees, the protesting Indigenous communities planted 30,000 saplings to replace the downed trees, setting aside an entire month for the plantation. Using social media, a nationwide call was made and people showed up from all over, including many from Kathmandu. Those who couldn’t be there in person sent rice, vegetables and other ingredients necessary for the planters to last a month. Alongside the plantation, cultural rituals were performed, following Mundhum, asking nature for its forgiveness. As a reference to the ongoing resistance, a Limbu scholar said, “There is no movement without Mundhum”. In defending nature, which is inextricably linked to culture, he must have meant both retaliation against the burgeoning neoliberal onslaught on the sacred landscape and creativity in defense of nature, which is inextricably tied to culture.

The Indigenous people demand this: the annulment of the “Pathibhara Area Development Committee”; The formation of the “Mukkumlung Area Development Committee” representing Indigenous communities and local stakeholders; and the creation of a development model for Mukkumlung based on the Mundhum philosophy as well as other non-indigenous local knowledge, culture and economy. In other words, the push is for a vision that fuses Indigenous philosophy with anti-capitalist ideology.

And in this push, there are new networks of solidarity that are forming, helping the movement grow in creative directions.

Early September 2024, artists, painters and performance artists from Yakthung Cho Sanjumbho, a collective of indigenous artists in Nepal, packed their belongings to travel to the eastern hills, reached the road’s end and trekked through the trail to climb atop Mukkumlung, alongside fellow activists and researchers. The objective was to create paintings for a protest rally against the cable car.

At the top of the mountain, climbing back down the trail through the forests, past the patches where new saplings were growing to fill the void left behind by the fallen trees, and while stationed in the hilly bazaar, Phungling, the artists spent the following few days finishing up their paintings.

Locals from the bazaar and adjoining villages gathered early in the morning on a Wednesday. Like easels on walking legs, the protestors carried the paintings the artists produced, of their mountain and the forest, and illustrations, some metaphorical, some real, of the cable car eating the mountain and the forest. The paintings were on full display to the onlookers — shop-keepers, passers-by, policemen on duty, office staff on a lunch break, school goers, and so on.

As part of their creative undertaking, the artists had also put together a dummy cable car. Four protestors volunteered to carry the cable car hanging by the bamboo culms on either side, as if it were a funeral procession. Toward the end of the protest, the rally formed a circle in a town square, and the paintings were put on display in the middle of the circle for the locals to absorb and take in. Following the Mundhum funerary ritual, the cable car was put on fire, and a shaman sang the final song of death as he fervently stomped on top of the section of the square on which the last remains of the cable car lay. A sight so captivating to behold, even the policemen tasked to control the protest were seen capturing on their smartphone the dance of death unfold, with their mouths gaped wide open. And then it rained. It seemed like perfect timing.

“I was born for this”

To wage a movement is not easy, and it is not easy when stakeholders of power on the other side of the battle lines have joined forces – the ambitious billionaire fueled by limitless financial capital; the aberrant mayor alongside his militant sycophants, the district administration office backed by anachronistic bureaucracy; and above all, the central and provincial states, historically led by the upper caste Hindu men, hellbent on inscribing Hindu names onto the Indigenous geography — its culture and cartography — as a necessary tool for continuing and deepening neo-colonial domination and control.

When measured in terms of sheer political clout and financial capital, there is a gulf between the crony capitalists and the indigenous movement. But movements run on something far more intangible and immeasurable — the quiet grit of the people and their immovable resilience, embodied by the very mountain they are defending — the ancestral land, the sacred landscape. That being said, one cannot afford to let the guard down because, in the blink of an eye, the crony capitalist machinery might strike again — to dismantle the Indigenous line of the guard, to down a thousand more trees, or who knows, something more sinister and more violent that is yet to unfold.

I asked Shree how long the movement may last, given the size of the adversary at hand. Casting a thoughtful gaze on the floor space between our respective chairs that set us about two feet apart, Shree slowly raised his eyebrows to cast his glance in my direction, and spoke in a tone that seemed to pair confidence with humility, carrying neither drama nor rhetoric, firm yet gentle, “Brother, I was born for this”.

Dr Sabin Ninglekhu's work intersects the fields of (urban) planning and social/indigenous movements. He is currently leading an international research project titled “Heritage as Placemaking: The Politics of Erasure and Solidarity in South Asia” focusing on cities in India and Nepal. Dr Ninglekhu's monograph, titled Afterlives of Revolution: Slum, Heritage, and Everyday City, is to be published by the Amsterdam University Press, Netherlands.