Progressive International: Can you describe what happened in Caracas on the night of President Nicolas Maduro’s kidnapping? What is the mood like in the country? We saw major mobilizations across Venezuela as people took to the streets to defend the government. How are people preparing to defend the Bolivarian Revolution in the wake of the assault?

Cira Pascual Marquina: I was about three miles from one of the bombed sites when the assault happened, so I heard the airplanes, that very intense drone, and then the explosions, which made the windows vibrate.

Of course, we immediately knew it was the U.S. attacking us; they had been building up troops around Venezuela since August, and for the last 26 years, Venezuela has been an objective of imperialism. When we learned President Maduro had been kidnapped, people started to walk very spontaneously towards Miraflores, the presidential palace, in defence of our sovereignty. At the march, everybody spoke with a lot of force, commitment, and a disposition for sacrifice, which is what the moment demands.

Meanwhile, on that first day, after having been witness to so much violence, others chose to stay home, and only a handful of stores opened, some with lines. Yet the most important thing is that the city remained at peace. There was a palpable sense of kinship, shared dignity, and a collective disposition to struggle among the people who gathered and spoke outside of Miraflores.

If I had to synthesise the mood of the majority—the Chavistas—it’s, on the one hand, anger, a lot of anger! But also, on the other hand, commitment to continuing the Bolivarian Revolution. And if you are committed to the revolution, you have the disposition to fight for it.

Not only the people, but the government has acted with clarity too. Delcy Rodríguez, now acting president, gave an address about 12 hours after the attacks, and she was surrounded by the whole military and civilian leadership. It was a powerful visual message of unity.

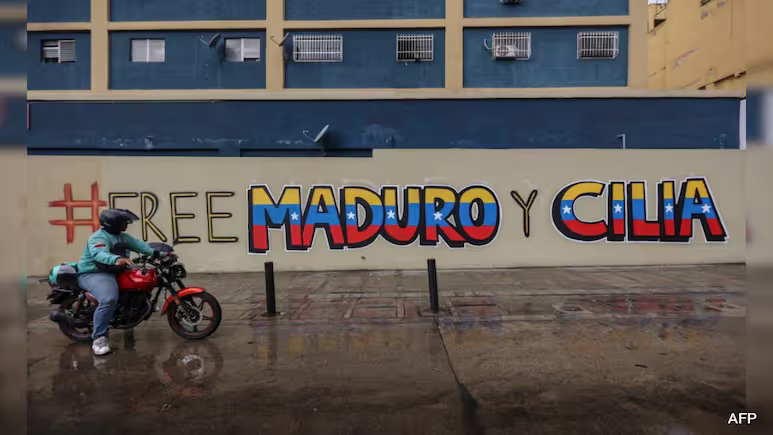

In her address, she said something that you now can see written on the walls of Caracas: “We aren’t anybody’s colony” [“No somos colonia de nadie”]. She also said, like Chávez and Maduro, that she has the disposition to have an open channel of communication with the United States government. And soon enough, there were announcements about the possible sale of Venezuelan oil to the United States.

When we talk about Venezuela’s deals with the U.S., some on the “left” are already saying what Venezuela can or cannot do. What Lenin, in the context of the Brest-Litovsk treaty in 1919, said to ultraleftists, some of whom eventually became collaborators of the enemy, is very relevant today: If someone puts a gun to your chest and demands your money, you give it. That is not giving up the project; it is a tactical concession. There might be some concessions made, but this should not be understood as a delivery of our sovereignty. The Bolivarian Revolution will not surrender.

The most important thing is that, as opposed to what Trump has said, the Venezuelan government is the government the people chose: a revolutionary government, a Chavista government. The person in charge now is committed to the same project as Maduro and Chávez. If this weren’t the case, you would not see hundreds of thousands of people marching in the streets of Caracas and around the country in support of acting president Delcy Rodríguez and the government, while demanding the return of constitutional president Nicolás Maduro and National Assembly representative Cilia Flores.

The people of Venezuela are with their government, and the government is with the people.

PI: Hybrid warfare aims to create confusion, demoralisation, and fragmentation. What practices have the communes developed to maintain collective morale and political clarity? And what could the rest of the world learn from these practices?

CPM: In 2006, Chávez declared that the objective of the Bolivarian Revolution was socialism. For us, the communes are the path toward that goal—and in themselves they are a concrete, living experiment in socialist construction. During the worst years of the blockade, the government was forced to concentrate on urgent issues and challenges, such as reopening channels for oil sales after the US’ unilateral coercive measures caused revenues to collapse. Even so, communes never ceased to be the strategic horizon of the Bolivarian Revolution. Indeed, it was precisely in the hardest of times, around 2017, 2018, 2019, that some communes began to flourish with force. One of the most remarkable developments of the past four years is that, after regaining a measure of economic stability, the government has once again turned decisively toward the communes, which now stand at the very center of Venezuela’s political life.

Venezuela’s communes are not autonomist self-governments, as they are sometimes imagined to be. Yes, they are territories of direct, assembly-based democracy where people come together to deliberate and decide collectively how to address their needs. But they are also the basic cells of socialism—and socialism, for us, is a national project. The aim is not only for people to gather in assemblies to deliberate over their problems and work hand in hand with the government to resolve them, but also for communes to come to control the means of production. In doing so, the social relations of production begin to change: the surplus generated by communal property is consciously and democratically regulated by the community. Production is thus oriented toward social need rather than accumulation, opening a real path to breaking with capital’s authoritarian and exploitative social metabolism.

In my commune, El Panal, located in a working-class barrio in Caracas, we have a meat processing plant, a garment-making workshop, and a soap-making plant, among other smaller enterprises. The surplus from all those goes back to the commune, and the commune collectively, in assembly, decides what to do with it: some of it goes towards the Pluriversidad, the commune’s educational initiative, and another part may go to paying the wages of the commune’s nurse or the maintenance of the commune’s ambulance, etc. This is substantive democracy at a small scale. From here, the communal metabolism must scale up to a national level, which we call the communal confederation and others call the communal state.

This turn of the revolutionary government towards the communes is highly relevant to understanding the massive support that the revolutionary government is receiving from the people. The people are not foreign to the project promoted from the “top”; they are at its core. People do not feel like spectators here. We are subjects of transformation. We do not feel like victims; we are the actors, even protagonists, in a revolutionary process with a socialist horizon, and the government speaks and acts in relation to the collective vocation of the people.

To give a concrete example of this synchronicity between government and people: over the past two years, the government has promoted nationwide popular consultations—a radical, democratic form of managing resources in which communes themselves decide how to allocate public funds and then carry out the projects through direct management of the funds and collective work. This process has sparked what we can only call a new wave of communalization.

Today, there are around 4,500 communes in Venezuela. While some had become extraordinary socialist experiments, beacons of light, really, it is also true that before the consultations, many were dormant or only incipient. However, the national consultations—promoted by President Nicolás Maduro and now set to continue under the leadership of Delcy Rodríguez—have activated the sleepy communes, turning them into living instruments of collective power.

Why do people stand with the government despite the certainty of continued U.S. aggression? Because this is not an imposed project: it is a collective, democratic process. People will fight for what belongs to them.

Contemporary capitalism fragments social life. One of the great achievements of the Bolivarian Revolution has been to begin weaving what has been fragmented back together: people in the communes no longer see themselves as isolated individuals, but as subjects of a national project of collective emancipation. For further reading, I recommend what Chris Gilbert has written in Monthly Review about Venezuelan communes forming part of an anti-imperialist project of national liberation.

In a commune, the simple possibility of participation—of assemblies where hundreds of people come together to decide what to do—rebuilds what capitalism and imperialism have torn apart. The first steps in reorganising society, both politically and economically, can already be seen in some communes. And that is what makes the Bolivarian Process that much more robust in facing the extortion U.S. imperialism is trying to impose.

PI: Although not unprecedented, the nature of this latest attack was perhaps unique in the speed of its execution. How do you wage a people’s war against an enemy that wants to avoid direct confrontation, limiting itself to carefully-choreographed clandestine operations or criminal proxies?

CPM: First, we must be clear about what happened in the early hours of January 3: the US attack and kidnapping of our president was a tactical victory for imperialism, which, unsurprisingly, appears to have been coordinated with the Mossad. Their technological superiority to carry out such an operation is undeniable. However, there’s a part of the story that is often not told: people fought back. More than 100 people were killed in the attack—most of them members of our armed forces who stood their ground defending the president alongside Cuban internationalists. Venezuelan civilians were also killed. Their blood speaks for something that cannot be erased: this was not a “surgical” operation, but an act of imperialist war against a sovereign people.

The tactical victory of imperialism, however, will not translate into a strategic victory. The people of Venezuela maintain our Chavista government, and our long-term project of the communes stands alive and well.

The people of Venezuela have been organizing for a people’s war for a long time. In military terms, we are now in a phase of resistance: the Bolivarian Revolution has been under attack for 26 years, and for the last decade, the country has endured an all-out economic war. This sanctions regime has crippled the economy, drastically reducing oil revenue, cutting off essential imports of food, medicine, agricultural inputs, and machine parts, and thus contributing to tens of thousands of avoidable deaths by limiting access to basic necessities and lifesaving treatments.

During the most difficult years, in the face of an unusual and extraordinary punishment campaign unleashed by the U.S. against the people of Venezuela, despite having less access to medicines and food, the pueblo, particularly those in the communes, continued to stand with their government. In short, this latest attack is not the beginning of the people’s war; it’s simply its intensification. Resistance, organization, and solidarity—together with the preparation of a people in arms (in the Venezuelan case, the militia, counting eight million)—have always been at the heart of the people’s war here, as was the case in Vietnam or Algeria. The most recent attack has only strengthened the determination to fight, deepening the collective resolve to defend the revolution, which expresses itself best in the communes.

Communes are inherently anti-capitalist formations. They do not accommodate the bourgeoisie; rather, they are spaces oriented toward overcoming capitalist social relations. In doing so, they forge class unity around a collective national horizon. It is precisely this dual focus—on national liberation and class-based transformation—that makes communes such resilient and powerful instruments of the Bolivarian Revolution.

PI: In the immediate aftermath of the assault, the stock valuations of major U.S. oil producers rose sharply. What is Washington after in its hybrid war against Venezuela? Is it just oil—or is it the broader Bolivarian Process? What threat does the success of the Bolivarian Revolution pose to the United States?

CPM: Let’s say first what everyone knows but must be said just the same: the stock market is a market for vultures. Obviously, they thrive on war.

In any case, to go back to Venezuela and the war that the U.S. wages against its people, I think you cannot separate the U.S. interest in the country’s oil from the overt imperialist intent on destroying our revolutionary project. Some say this is “only about oil.” Others argue that Washington has unleashed a campaign of collective punishment to discourage other countries from moving in Venezuela’s direction and to destroy the moral force of the Bolivarian Revolution. These objectives merge under the umbrella of attempting to assault Venezuela’s sovereignty. Venezuela is a sovereign nation with immense natural resources, and imperialism seeks to subordinate the country to its own geopolitical and economic aims.

The Bolivarian Revolution is under attack because the people of Venezuela have defined a sovereign project with a socialist horizon, and because the Venezuelan state is in command of the country’s oil reserves. The two cannot be separated.

A socialist, national liberation revolution with oil under its ground? This is a real problem for the United States!

If Venezuela didn't have oil resources, it would still be a target of U.S. imperialism, but not with such intensity. At the time of the January 3 attack, U.S. forces had dozens of warships with tens of thousands of troops near Venezuelan waters. The raid itself involved over 150 U.S. aircraft, and the attack was coordinated among 20 different U.S. bases across the Western Hemisphere. The operation took months of planning that even included building a full-scale model of the President’s compound to rehearse the attack.

The target? A nation determined to be sovereign and socialist, sitting on top of the world’s largest reserves. In this case, the two—sovereignty and oil—go together.

PI: How do you view the international response to the attack? Many states have condemned the U.S.'s actions, but many also omitted any call for President Maduro's release or endorsement of his government. In the context of such overt aggression, what does this "partial solidarity,” which rejects the U.S. method but not necessarily its goal, reveal about states’ readiness to navigate a world order still dominated by U.S. imperialism?

CPM: While some governments have issued only timid or “light” rejections of the attack, the reality is that most of the world’s population lives in countries that have, in one form or another, condemned this flagrant violation of international law. Colombia’s president, Gustavo Petro, went so far as to call Delcy Rodríguez directly and invite her to Bogotá—an act that amounts to recognizing her as acting president. Many other heads of state have followed suit in different ways. That matters, and it is positive.

What is far more troubling, however, is the de facto silence of the United Nations. There has been no resolution, and there will not be one. At this moment, the UN appears less like a guarantor of international law and more like an institution that has been rendered practically inoperative.

On our side—the side of the working people of the world—there is already a global movement that first mobilized against the Western-backed Zionist genocide in Gaza. Palestine was a wake-up call for millions of people, forcing many in the Global North to confront the realities of colonialist and imperialist violence. Now the attack on Venezuela is becoming a second wake-up call, one that expands the perspective of people who opposed the genocide but saw it as an isolated atrocity, as an aberration.

The same structures and networks that brought people into the streets against the genocide are now mobilizing for Venezuela and against U.S. imperialism worldwide. What has happened in Venezuela lays bare what imperialism really looks like in its current phase of decline: the use of outright violence to achieve its aims when governments and peoples refuse to comply with its dictates.

We need to understand this moment as part of a broader, emerging worldwide working-class movement against imperialism. At the same time, the United States is now bringing home to roost the very forms of violence it has long imposed on the Global South back into the imperial core itself, as its internal political order takes an openly fascistic turn.

So we see multiple signs that the working class in many countries, including in countries of the Global North, is beginning to recognize imperialism as a common enemy and now understands the need to fight together against that common enemy. People in the United States who are resisting ICE, which is really today’s Gestapo, are beginning to confront the violence at home that we, in the Global South, have faced for many decades.

As we collectively come to understand what imperialism truly is—through Palestine, through the way its old methods have come home to roost, and now through the attack on Venezuela—the conditions for overcoming it are beginning to take shape. Here in Venezuela, this gives us hope.

PI: Throughout its history, the U.S. has routinely infringed upon and disregarded other states' sovereignty with limited to no consequences. Given this, is the core crisis not merely one of international law, but of its asymmetric enforcement, where the international order is ultimately governed by raw power hierarchies?

CPM: Indeed. Not long ago, Libya—to take just one example—endured practically the same blatant disregard for international law at the hands of the so‑called international community currently in charge of the UN, if not worse.

There is no mystery here: U.S. imperialism has shown its ability to wreak havoc for more than a century, and the new multilateral spaces where some of us placed hope only a few years ago—specifically BRICS—have so far failed to issue a response in the face of this attack.

But I know this: the people of Venezuela are not alone as the people of Libya were fifteen years ago. Pieces are beginning to fall into place that could bring working people of the Global South and the Global North together, because the enemy’s intentions are no longer hidden—they have been laid bare for all to see since the genocide against the people of Palestine began. And when the working classes of the periphery and the imperialist center unite in common struggle, then we can truly say that the sun is starting to break over the horizon.

PI: What can movements, unions, and political parties around the world do now to stand with the Venezuelan people and the Bolivarian Revolution as it faces this escalating assault?

CPM: I think these days it’s important that people mobilise in the streets, but also that people really try to understand what is going on here and counter the mainstream media, which totally misrepresents reality. They say that people are celebrating the attack, and while a few hundred may have gathered to do so in Miami, hundreds of thousands are coming out to the streets in Caracas every day to reject the kidnapping and support the revolutionary government. They say that we live in a situation of absolute chaos, and actually, we are living in a country that’s at peace.

We have to counter the narrative of the corporate media, which serves the interests of a tiny few and clearly reproduces lies to manufacture consent for war and cover up imperialist violence: their lies are part of a multiform war against the people of Venezuela and our sovereign project. That may be the most important task of all: to break the grip of the mainstream story. It isn’t easy—we haven’t been able to do it on our own—and that is precisely why it is so crucial.

To get good information, there is one relatively simple pathway that my colleague Chris Gilbert and I have been insisting on: it is to listen to the leadership of the revolutionary government—to Delcy Rodríguez, to Diosdado Cabello, to Vladimir Padrino López. They have the full support of the people, and the message they convey is clear.

Finally, I would urge those who wish to defend the Bolivarian Process to learn about the revolution’s strategic horizon, about a project that is anti-imperialist, socialist, and profoundly communal. Defending Venezuela’s sovereignty is, of course, essential at this moment. But Venezuela's sovereignty is intertwined with the communal project that is rooted in substantive democracy. In a world darkened by war and disinformation, communal construction is not only a political project, it’s a living source of hope.

So that is what I would say to people: take to the streets to protest the imperialist attack on Venezuela; seek out the truth by listening to the leadership of the Bolivarian Revolution; challenge the mainstream narrative; and learn from—and be inspired by—the living force of the communal movement.

Pascual Marquina is an author and popular educator at the Pluriversidad Patria Grande, the educational initiative of El Panal Commune and a professor at the Universidad Bolivariana de Venezuela. She is also the founder and co-host (with Chris Gilbert) of the Marxist education program and podcast Escuela de Cuadros.