On 3 November, California voters passed Proposition 22, a ballot measure backed by app-based “gig” companies that exempts them from classifying their estimated three hundred thousand workers as employees. Included in Proposition 22’s fine print is a requirement that the measure cannot be modified with less than seven-eighths of the state legislature’s approval, all but ensuring it cannot be overturned.

The measure’s success is a landmark in the story of rule by the rich. Were there any doubts before, Proposition 22’s success proves that capitalists can write their own laws — you can expect every executive in the United States to take notice.

Companies including Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, Postmates, and Instacart poured $205 million into the “Yes on Prop 22” effort to pass legislation that exempts them from labor law requirements relating to health care, unemployment insurance, safe working conditions, and other benefits (potentially including workers’ compensation, such as death benefits, as detailed in this harrowing Los Angeles Times story). The opposition to Proposition 22, largely composed of unions and allied labor organizations, raised $20 million, leaving it outspent ten to one.

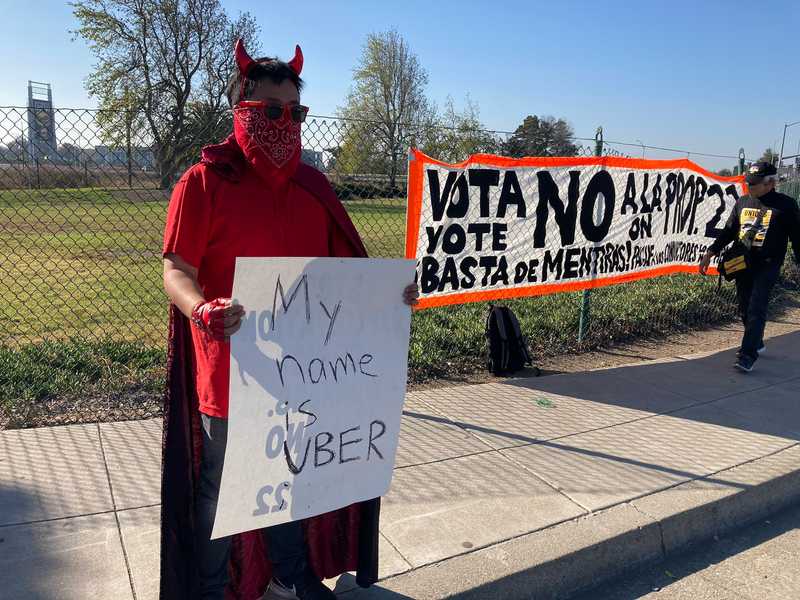

The proposition’s backers bombarded Californians with misleading mailers, ads, and in-app notifications in the lead-up to the vote. As the Los Angeles Times reports, Yes on Prop 22 spent $628,854 a day: “In any given month, that ends up being more money than an entire election cycle of fundraising in 49 of California’s 53 House races.” In addition to hiring nineteen public relations firms, some of which made their name working for Big Tobacco, the companies bought surrogates, donating $85,000 to a consulting firm run by Alice Huffman, the head of California’s NAACP [National Association for the Advancement of Colored People], effectively allowing them to cynically present themselves as on the side of racial justice, even as the measure will further immiserate drivers, the majority of whom are people of color. This veritable flood of money makes Proposition 22 not only the most expensive ballot measure in California history, but in the history of the United States.

The crux of the measure is about exempting gig-economy companies from AB 5 (Assembly Bill 5), a state law that requires companies to grant workers employee status based on the “ABC test.” Laid out in the California Supreme Court’s Dynamex case, the ABC standard says that a worker is an employee, rather than an independent contractor, “if his or her job forms part of a company’s core business, if the bosses direct the way the work is done or if the worker has not established an independent trade or business.” Despite tech executives’ insistence that their companies are mere platforms rather than employers, drivers for gig-economy companies clearly meet the ABC test, which led to the race to write an exemption.

This boutique carve-out is an existential question for gig-economy companies, which is why they were willing to shell out so much cash to secure it. None of these companies turn a profit. Uber lost $4.7 billion in the first half of 2020. Their entire business model is based on labor arbitrage: it won’t be profitable until they can adopt technology that automates drivers out of their jobs — meaning they will never be profitable, given how far this technology is from being workable — but in the meantime, they operate at a loss, subsidized by venture capital, by evading the liability and risk that comes with employer status. As markets opened on the morning of 4 November, Uber saw a 9 percent jump in shares, while Lyft rose 12 percent.

Were these companies required to comply with labor law, they’d sink. For example, as the Prospect reports, Uber and Lyft’s refusal to pay into California’s unemployment insurance fund has saved the companies “a combined $413 million since 2014.” Instead of paying for the benefits and protections that the law mandates, these companies will now only be required to offer limited benefits and a wage that works out to $5.64 an hour — rather than the $13 an hour they’d receive as employees under the state minimum wage law — according to researchers at UC Berkeley’s Labor Center.

There’s reason to think even this historic victory won’t be enough to save the likes of Uber. The company, the most visible of gig-economy parasites, is facing opposition across the United States and around the world. As Edward Ongweso Jr writes, governments at both the national and state level are fighting to force Uber to pay billions in evaded taxes, and a 2019 strike on the day of the company’s public offering was followed by further worker action in Brazil, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, and Ecuador. Further, “Uber is losing legal challenges in France, Britain, Canada, Italy, where high courts have either outright ruled Uber drivers are employees or have opened the door to lawsuits reclassifying them as such,” writes Ongweso Jr.

But even if Proposition 22’s advocates are ultimately doomed — a big if, and one that doesn’t much matter for the countless drivers currently relying on their algorithms to pay their rent — their quest to shirk responsibility for workers is not unique to gig-economy companies. The tech industry is united by its foundation in labor arbitrage, the exploitation of legal loopholes. This is their claim to innovation. And that doesn’t only affect low-wage workers: the majority of Google’s workforce, much of it white collar, is composed of independent contractors. This is the future of work for all of us if Silicon Valley has anything to say about it.

The enshrining of a new category of workers whose hard-won rights no company is bound to respect won’t remain restricted to gig-economy serfs in California, either. Since the Proposition 22 result came in on the night of 3 November, the heads of the victorious companies have announced their intent to export the model nationally. “Now, we’re looking ahead and across the country, ready to champion new benefits structures that are portable, proportional and flexible,” said DoorDash CEO Tony Xu shortly after the ballot measure passed. Lyft sent out a celebratory email, calling the law “a groundbreaking step toward the creation of a ‘third way’ that recognizes independent workers in the U.S.” “Prop 22 represents the future of work in an increasingly technologically-driven economy,” proclaims Yes on Prop 22 in a celebratory statement posted to their website.

There is little organized opposition among elected officials to these executives’ intent to take their success in California and federalize it. These companies launched their offensive in Nancy Pelosi’s own district, and the House leader didn’t prioritize fighting them. While Joe Biden and Kamala Harris say they oppose Proposition 22, there is little evidence of Biden ever sticking his neck out to fight for workers’ rights if it wasn’t for a campaign photo op, and Harris has unprecedented ties to Silicon Valley. After all, such affinities run in her family: Tony West, her brother-in-law and a high-ranking official in the Obama administration, wrote the gig economy companies’ legal strategy for misclassification.

No one is coming to save workers. The future hangs on working-class people organizing themselves to defend their rights, even as capital deploys an effectively infinite slush fund to stop them from succeeding. Unity among workers, both unionized and not, employees and independent contractors alike, has never been more pressing. If Proposition 22 is anything to go by, the future of even the limited democracy still exercised in the United States depends on it.

Alex N. Press is an assistant editor at Jacobin. Her writing has appeared in the Washington Post, Vox, the Nation, and n+1, among other places.

Photo: Twitter